What I love the most about teaching at a community college, which is what I do, is that the education we offer provides under-prepared students with a new type of focus and motivation. We also provide cheaper credits to students who don’t want to undertake lifetime student-loan-repayment programs. Because we’re accessible and low rent, mos’ def, we teach an amazing cross-section of students in the community college, from returning vets, fresh off the deserts of Iraq, to recovering meth addicts, to former-stay-at-home mothers of five who are finally having their turn, to high school students who are taking advantage of Minnesota’s post-secondary schooling option.

And with 150 or so of such people in my classes every semester, ’tain’t never dull. But even when I get overwhelmed (as I am this week, the last week of classes, when research papers, persuasive essays, portfolios, etc. are flying with great force towards my gradebook), I always have an appreciation for my students’ efforts to get themselves to college. They may not do it well, and they may not do it for the right reasons, but every now and then, the education sneaks up on them–GOTCHA– and reorients their lives.

This was evident in an excerpt from an email sent to me by one of my students a couple of years ago. This particular student, raised in a household of fear by an alcoholic mother, has earned her way through two years of college by working at a variety of jobs, the most lucrative of which is exotic dancing. Her life story is heartrending, littered with abuse, abandonment, rape, and bipolar disorder…yet she is one of the most intelligent and thoughtful students I have ever taught. When I received this email late one night, I thought she was just sending me a copy of her posting to the online discussion about a Barbara Ehrenreich essay we had read (an excerpt from her book Nickled and Dimed). However, this student, then working at Goodwill, was feeling frustrated with the way the online discussion was going (students were adopting a “if you don’t like working at Wal-Mart, just quit and get another job” stance), so she sent me this email to open her history and hammer home to me how transformative a college education can be:

I just wanted to share with you that I bought Barbara Ehrenreich’s book Nickled and Dimed, On (Not) Getting By in America. I identified with her experience so much it was a little scary, except of course that my slave-wage jobs were not research for a book and I was working to survive and did not start out with a car or any back up money…It will certainly be fun to leave it on the breakroom table at work. Although Goodwill purports to be one of the largest employers of former welfare recipients, I would actually make more money working for Wal-Mart, but I won’t because my manager at Goodwill is a nice crazy, older lady who is pretty easy to get along with and even though sifting through donations is often dirty and hazardous work, it’s kind of like looking for buried treasure, or at least that’s how I like to be optimistic about it. Goodwill also denies its employees full-time status in order to dodge giving them health benefits. I was disappointed to learn that even though I only make $6 an hour, have no benefits, and only work 20 hrs a week I am now denied almost all healthcare from MNCare because I am single, have no dependents, and my Goowill job puts me at 75% above the poverty line. I found this hard to believe until I read Nickled and Dimed, now I am more motivated than ever to pursue my dream job, and will at least more gratefully suffer through 10 more years of poverty than I previously have. I was really discouraged before, after reading her book I realize I am actually much better off than most people even though I too worked full-time at one point and lived in my car. It’s not a matter of people being lazy anymore so much as it is working ‘til exhaustion and still having nothing, easy to become disillusioned with the American dream, I am fortunate that I have found a way to go to college at all…I’m glad it was one of our assignments to have read part of this book, and I just wish that some of the more fortunate people…could live a month in a low-wage employee’s shoes, their feet would be very sore and their eyes would be more open…

This email humbled me and took me back to a very thoughtful place, in terms of what I do in the classroom. Sure, I get annoyed with students and their hectoring me about grades. Sure, I’m going a bit crazy this week–I never realized when I was in college that my professors weren’t just lolling about in their offices, eating hard candies out of a bag kept in their top drawers, playing Corridor Crash in their rolling chairs but, in fact, were overwhelmed and stressed out and edgy, too, as they ate their hard candies and played their rolling chair games. And sure, I pretty much wish most of my students were more consistently committed to their work.

Then again, if they’re not living in their cars, or are finding post-rape counseling, or have just moved out from an abusive boyfriend, maybe there’s a place in my teaching for an attitude of “Okay, so this week, you missed an assignment, skipped class, lied to my face, and then turned in a crappy paper. Yet I couldn’t be more delighted with you. Because you’re doing what you can. You’re putting one foot in front of the other. You’re bruise-free; you’re talking about the cruelty instead of passing it on; you have a bed. This week, my inconsistent student, you are in college, and if anything’s ever going to make a lasting change for you, this is it. Come on in and give me more of your distracted, stumbling prose. We can work with it.”

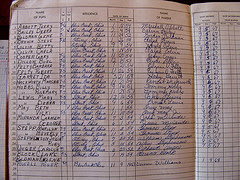

And with that, I’m off now to grade my 124th terribly-written paper of the week. Of course, each piece of dreck has

its own story

and, therefore,

its own worth and charm.

Leave a Reply