In 1906, my maternal grandfather picked up a typewriter and threw it at the principal of his high school. He was 14.

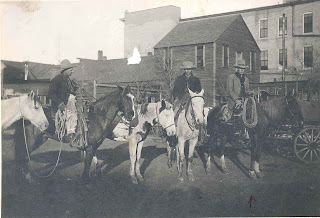

Shortly thereafter, he left his hometown in southern Minnesota and made his way to Montana, where he found work as a “hired hand”–a cowboy, in more romantic terms. With the help of his horse, Pickles, my grandpa Julian roped, herded, sang, and ultimately homesteaded a plot of land outside of Wolf Point.

And then, in 1917, he followed the call of war, leaving Montana for training in Washington state and ultimately service on the battlefields of Europe. There, family lore has it, his eagerness and quick feet earned him a job delivering messages on the front lines; his proximity to constant explosions resulted in diminished hearing, something that plagued him the rest of his life.

At the close of World War I, Julian returned to Montana and his homestead, until family obligations (taking care of his mother after his father’s death) pulled him back to Minnesota. With his days as a cowboy and a soldier behind him, the rest of my grandfather’s life must have felt anticlimactic. Certainly, he married. He fathered five children during the Depression and the early days of World War II. He became a rural mail carrier.

He also became an alcoholic, one who used a leather strap and his fists on his wife and children in his fits of rage. He taught them capitulation, powerlessness, and patterns of passive-aggressiveness that still play out, generations later.

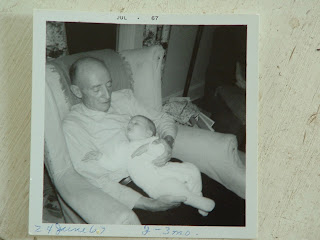

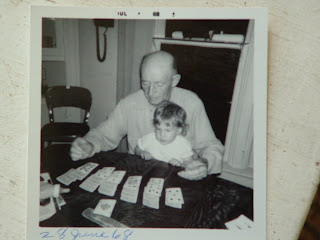

As a grandfather, he was kind. I remember sitting on his lap, reading the comics with him; I remember having to yell my words to him to be heard. I remember his fondness for me. Even more clearly, I remember some years later being fifteen, at a party, and catching a whiff of whisky. My knees buckled with the rapid, sensory memory of “Grandpa.”

When I was eight, he was found dead in the kitchen, having outlived my grandmother (she, a decade younger than he, had passed away a year before; my mother and aunt can never forgive themselves for always believing that she would get some “good” years, some “free” years after his death…for surely he would die first–but then he didn’t). At his time of death, he was in his pajamas; he was alone.

More profoundly than these stock details, squirreled away in my memory, I remember my mother’s tears, the trauma in her voice, as she told me about the time her dad’s drunken rage reached a new height. He not only went after the kids, but he tore after their mother, chasing her and hitting her with a broom, until he finally turned over the dining room hutch. My mother fled the house, hoping to find help for her mother from the neighbors, who were good friends. As my sobbing mother hammered on their door, she saw them looking out the window at her and then retreating, closing the curtains and willfully turning a blind eye to the violence and chaos next door. In that moment, a certain faith–in community, in neighborliness, in the willingness to stand up for what was right–shriveled inside my mom. And back at home, the rage continued, unabated.

Such is it, therefore, that when I think of my grandfather, I remember him in his full human complexity, through his adventures, his work, his service, his kindness, his temper, his fallibility.

On this national day of remembrance, I don’t need to vaunt my grandfather as a hero. I don’t commend him for his “sacrifice” of military service–although I think it was a valid career choice for those years of his life, one that counts as a contribution (in the same way that I think that my sister, who has taught the academically-unprepared kids of inner city gangbangers, contributes to making a difference…or the nurse who sang to my newborn as she danced him down the corridor to me for a feeding on his first night of life made a difference…or the undiluted passion of Paul Wellstone made a difference).

But the truth is that my grandpa Julian was just a man, one who created momentum in his life through a violent act, who was trained into the violent ways of a bloody war, and who then used a convergence of tendency and training to elicit a flinch, a cowering, a hand held up to shield a blow.

As I look at all the flags hung so high on this Memorial Day, I think, with a perverse kind of affection, of whisky and bombs and poker and loudly-told stories and jokes. He is in my memory, this grandfather of mine.

Leave a Reply