My great-aunt Ethel and Grandma Dorothy as girls in Montan

The Saturday after his mother’s memorial service, my Finnish father, who would regularly answer the direct question of “What are you thinking right now?” with “I don’t know,” talked to me about his life. As it turns out, he was more than just my parent, the guy who mowed the lawn and directed choirs and churned out homemade pear walnut ice cream (using Thomas Jefferson’s recipe); he was a fully-historied human being with a holster of experiences I’d not known about.

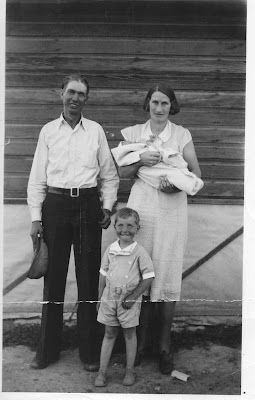

Francis and Dorothy as a young couple, holding new baby Larry; my dad is the three-year-old in the front.

Francis and Dorothy as a young couple, holding new baby Larry; my dad is the three-year-old in the front.

On that Saturday night, as Dad and I sat at the dining room table alone, I learned that my grandfather–reputed as gentle and taciturn in family lore–had, through wordless reproach, made my father feel stupid, even worthless, for my dad had the ill luck to be born with a beautiful tenor voice into a world where handwork was valued. On the ranch, that this boy, my young father, would someday sing Die Fledermaus was secondary to his inability to fix a broken combine.

My dad (looking a bit uncomfortable), my grandma Dorothy, my grandpa Francis, and my uncle Larry

Because of family expectations, my elegant, artistic dad spent his teen years on the back of a tractor, circling in the fields; it was then and there that he began to shout songs to the clouds, angling for any activity that would make the time pass and draw his attention from the worry of a mechanical breakdown–which would require he seek help from big men in dirt-covered overalls, men who would squint with quiet scorn at his “useless,” tapered pianist’s fingers.

That night, as words poured forth from my father, he admitted to me, “My father and I never had conflict. We always got along. But we were never close. In fact, Dad would never assign me chores or tell me what to do on the farm–I could have stayed in the house all day, as far as he was concerned. It was Mom who, to keep peace, would notice what needed doing and then send me out to work. I’ve noticed that Finnish families, maybe all Scandinavian families, are matriarchies in which the women take the initiative. And the men like it that way. They’re comfortable with letting someone else take the lead and make sure things get done; that’s one of the things I like best about your mother and what my dad liked best about my mom.”

Awash in my dad’s reflections, I also learned that after high school, Dad was going to attend the University of Montana-Missoula but first won a scholarship for the summer to Billings Business School for being the 3rd-fastest typist in the state. So he took shorthand there and a vocabulary-building class in the mornings. He lived that summer just outside of Billings on his Aunt Louise’s farm (she who sang “How Great Thou Art” at the memorial), where he slept in the bunkhouse with his cousin Stanley. Everyday, Louise made my dad a lunch to take to school: a baloney sandwich. Part of the agreement about his living in Billings that summer and being released from ranch chores was that he would have to work, so he got a job with Service Candy and spent his afternoons filling vending machines with candy and cigarettes.

Then, one day, Phillip Turner, the conductor of the choir at the private liberal arts college in Billings, Rocky Mountain College, came into Service Candy and said he’d heard about my dad’s voice (from whom, no one knows) and asked that he consider attending Rocky that fall. When Dad said that he already had a scholarship to attend the university in Missoula, and he needed that money, Mr. Turner pointed out that Rocky had a “valedictorian scholarship” for $300, and my dad would qualify for that. Thus, in the July before he started college, my dad changed his plans. Grandma liked the idea of Rocky, as it was a church-affiliated college. With her approval, his course was reoriented.

A year later, having completed his freshman year at Rocky, Dad was ready to get away from Billings–more accurately, to get away from the ranch that was a mere 40 miles from Billings, a place he was still dutybound to each weekend, a place with an endless expectation of willing work. Plotting his escape, my dad applied to three Minnesota schools (liking the fact that his dad had grown up there): Hamline, Macalester, and Carleton. Ultimately, he decided on Hamline…but his folks told him he couldn’t go–they’d not help him.

He said he was going anyway. And he did.

For the next three years, every semester, just when Dad didn’t know how he would pay the tuition, a check for $500, the exact amount of tuition, would come in the mail from his mother, my grandma Dorothy. Even thirty-five years later, both of Dorothy’s sons remembered fondly, “If it weren’t for Mom’s egg money, we never would have gone to college.”

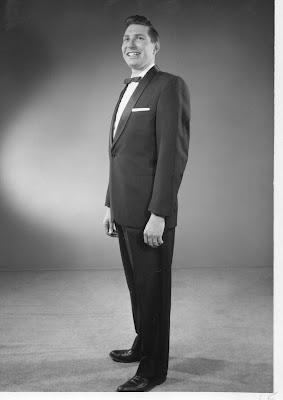

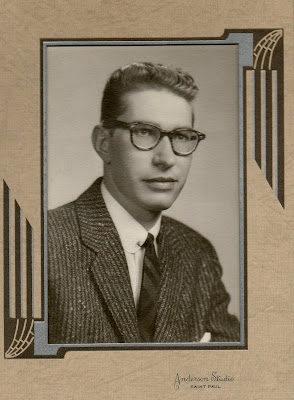

years and then in a professional picture a few years later

My dad during the Hamline

If it weren’t for my father’s talking that night in the wake of his mother’s death, I never would have known that my grandma, the woman who, at the end of her life, needed an elevating chair to help her stand up, had loved to dance. My grandfather would not dance, being too shy, but while he leaned against the wall, she would circle ’round the floor at the dances held in the local schoolhouse, turning, swirling with other fellows in the community, a fact that made her two sons elbow each other and snigger that another man was touching their mother, and she was having fun at it, too.

Because of the words her death inspired in my father that night, I don’t picture Grandma Dorothy in heaven as I remember her on earth–sitting in a purple recliner with an oxygen tank next to her, complaining of dizziness, elevated blood sugar, shortness of breath.

more vital,

kicking up her heels

against the backdrop of a broad Montana horizon

as she waits for her cows to come Home.

Leave a Reply