I live next to the largest body of fresh water in the world in terms of surface area. Because I have a long bendy straw, and I am very good at leaning out my window, I am never thirsty.

And because I am always careful to suck up my requisite sixty-four ounces per day, the water levels would take quite a hit, were it not for the forty-two creeks in town that continuously feed the lake.

Not incidentally, forty-two creeks and a big lake perk up some sweaty arse in the heat of August. For those few days when the temperature hovers near 90 degrees, we just pack up our beds and pillows and drop them into the frigid waters of the lake, where we recline in perfect comfort.

Yea, Lakey is frigid. Interestingly, when something is so enormous, it is slow to warm and slow to cool, rather like 1970’s tv detective Frank Cannon closing in on his suspect during the episode “Girl in the Electric Coffin.”

He didn’t rile easily, that Cannon, but once he had a scent, there was no stopping his drive for justice. Cannon and the Big Lake both exist in a state of intriguing contradiction: cold when it’s warm and warm when it’s cold.

Of course, Cannon actor William Conrad died in 1994 of congestive heart failure and has been persistently cold since.

Lake Superior, however, swishes on and, as it does, warmed a bit this past August–two months ago now. For several glorious weeks, we were actually able to inch our toes into the relatively-balmy 53 degree water, eventually shoving in the whole foot, and when that went numb, wading to the ankle. At some point, the impulse to plunge would overtake the screaming messages from our nerves, and we’d shimmy in up to the groin or go Full-On Fool and submerge every last follicle.

For eleven beautiful minutes, the heat of the day would drop away, and we’d swim and pull up hunks of eroded concrete from the lake bottom,

and then, suddenly sideswiped, we’d be struck with the paralysis of shit-damn-holy-hell-that’s-cold-water-and-I-don’t-care-if-it’s-88-degrees-outside-because-my-innards-are-now-a-box-of-Bird’s-Eye-frozen-peas. And really, if I have only one rule of parenting, it’s this: when the five-year-old utters anything starting with “shit-damn-holy-hell,” it’s time to towel off and go get cocoa and a scone.

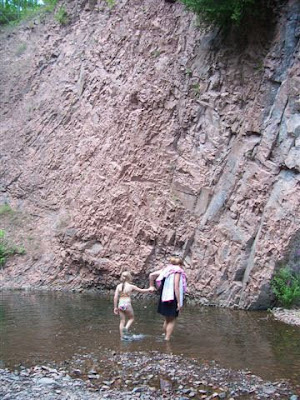

On one particularly-spirited day this past August, with out-of-town visitors in tow, we launched ourselves on a progressive tour of the city’s swimming holes, creeks, and polar plunges. In one afternoon, we hit four different spots, and at the end of it all, fell into an exhaustion entitled The Day of All Summer Days.

That day in August seems far removed now; but it resonates with what I feel this mid-October. When I hop into the lake in August, it’s a way of embracing the peak of a particular season–it’s me in my twenties, quitting my job as a nanny to drive to Graceland in Tennessee and Hot Springs, Arkansas, and White Sands, New Mexico, and Austin, Texas, and Boulder, Colorado, in a big swoop of “cuz I can” roadtripping abandon. The crest of summer, like that period of my youth, is golden and evanescent and fugitive.

And now. I’m forty-one, and I’m the embodiment of October 20th; I’m a breathing mid-autumn day. After we eased through June, July, August, fall set in with jarring swiftness. The overhead light of summer angled sideways and became slanting, mellow, softer. Everything in the world blazed briefly–orange and red and saffron–and then, in the midst of my gasp about its beauty, began the decline into rust, amber, chestnut. Fall and I are fading into an abatement of our peaks, and starkness looms.

Curiously, being just past the pinnacle, a tidge beyond the brightest blaze, a week past the sell-by date, well, it leads me into a feeling of harmony with bigger, deeper life junk. Although leaves have fallen from the trees and crunch underfoot (on my body, the leaves are called “breasts”; unbound, they too crunch underfoot), and although the lake is too cold to touch (on me, no such thing exists), and although ripening has morphed into waning,

I like it.

Fall, and my forties, are a season of ebbing. We are less fertile; we are less flexible; we are less free.

Yet we are full of texture; we perceive the rhythm of the full cycle; we appreciate that lessening can result in abundance.

We suspect, in our declination, that winter may be the richest of all seasons.

After all, there will be cocoa.

Leave a Reply