I haven’t seen the Spiderman, Iron Man, or Batman movies of recent years.

I don’t applaud politicians who promise to change our lives.

I don’t get all weepy over photos of my grandmother sitting in a big leather chair, doing her tatting.

I sometimes think members of the military are in it for the job–you know, so their families can eat–more than to sacrifice themselves defending their particular country’s version of “values of freedom.”

You see, I’m not much given to hero worship.

In fact, I chafe at the easy manner in which the word “hero” is thrown around, at the craving people have to laud something, no matter how vapid, at the compulsion to exhalt the world by slapping onto it such a label. People are people; sometimes they shine; sometimes they drain. We are all of us just us’ns, and to try to sort everyone onto tiers is exhausting, purposeless.

Flawed and full of smells, we are just us, we people.

That noted, I have to admit that often this is more of a principle than a reality for me. I do admire some others. I do look down on certain schmoes. I do vaunt others.

…but my rankings are not on a scale of heroic. That feels too cinematic and contrived. That feels like a one-armed Matt Damon on a zip line, whizzing through a jungle to retrieve a secret code before the bomb explodes in a lair where Cameron Diaz is being held by agitated guerillas. To tell you true, I’m equally put off by the Readers’ Digestian notion of “everyday heroes”–those people who saved puppies and started foundations and knitted mittens. Misread me not: they have done good things. However, I don’t think it’s too much to ask that all people attempt, in their own ways, to be their best selves, to do the things they think they can in the world. If we keep the bar set at the point of Reasonable Expectations for Humanity, then these everyday heroes are actually just doing what they should be. Comedian Chris Rock has a riff on this idea wherein he rails at talk show audiences that clap wildly for any African-American man who sits on stage and announces proudly, “I work for my kids. We throw the ball around on weekends.” Because expectatations have slid so low, the audience and the man greet his announcement with praise, with a feeling of “What a hero!” Chris Rock is quick to holler, however, “Don’t. applaud. that. man. for. doing. exactly. what. he’s. supposed. to. be. doing. Don’t treat him like he saved the planet because he managed to show up.”

At best, Us Good ‘Uns display a certain integrity or follow the ordinates on a particular moral compass (which, notably for me, don’t have to align with traditional views of “moral”; a person can be an admirable degenerate, so long as he or she is true to an impulse that remains essentially benign). At worst, the Us Bad ‘Uns bring to life a desire to hurt weaker, smaller, younger, softer.

Everything in between is just people being us.

Therefore, as you have probably seen coming, I get particular gratification out of bumping into something special, someone who stops me short and makes me inhale sharply.

Surprise me, Sailor.

To wit:

In the midst of a stretch of trying days–and not in any overt way, wherein I feel granted the right to collapse and weep on the duvet, clutching Kleenex to clavicle, but more in an ongoing, grinding way where I try not to carve the words “Help me” into the living room wall with a bloody whisk–I have found soppy comfort in a thing. In the midst of a week when I rushed forward when I should have held steady, when I lost several nights’ sleep with an agitated boychild, when I wonder if the family isn’t maybe being slowly offed by a carbon monixide leak (or why else do we all feel this way?),

I touched a good thing.

And if I ever forget to slow down and touch a good thing, may they box me up and put the casket on the pyre. Better yet: bypass the casket.

The good thing was a she, young and blue-eyed, with a charming bit of a lisp. She helped me refind a sense of possibility during a weekend where everything was dark and negative, a weekend when I was ready to go out and buy a VW van just so I could drive off into the sunset in it, cranking Neil Young and savoring the melancholy of dusk.

This girl is nine; she wants to be an actress; she likes to catch tadpoles; she is my daughter’s good friend; she has Type 1 (juvenile) diabetes. Mostly, she’s just a white kid growing up in a middle class family in the Midwest. She has seen High School Musical the requisite number of times.

While she’s been in Girl’s circle of friends for the last few years, and we’ve had her over for playdates and birthday parties, we’d never ventured with her into the larger commitment known as Preadolescent Sleepover. Because, er, you know, it’s a little intimidating to be the adult in charge of someone who could potentially die if you’re not paying attention.

However, now that Friend A is nine, nearing an age where a certain amount of self-care is a valid expectation, we decided to extend the invitation, something which, gratifyingly, was greeted with shrieks and hugs and statements that she had never been so excited in her whole life, about anything. It probably helped that we were also offering up pizza and a ride ON THE CITY BUS downtown to watch the yearly Christmas parade with us, before the actual sleeping over even commenced. Not only had Friend A never ridden on a city bus, she had never been to a live parade before. There was quivering.

Seriously, you can’t help liking her a little bit already, can you?

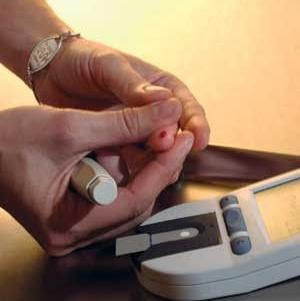

When her mother (in a separate post, I could probably make a case for this woman–with four kids, an out-of-town husband, an oldest daughter down with daily migraines, unable to get an appointment at the Mayo Clinic due to villainous paperwork–as heroic) dropped her off, they gave me the training I would need: I met the meter and the whole kit used for bolus doses; I met the pocketful of carmel rice cakes; I met the Ziploc baggie of glucose tabs (most effective and dramatic in the case of plummeting numbers); I heard her numbers (“she’s been at over 300 this week…running high because she’s so excited for this sleepover…but today she has a new site for her pump and new insulin, so she’s evening out…call anytime…anytime”); I was told the schedule for blood tests (after dinner, right at bedtime, two or three hours after bedtime, and then we’d see). My head spinning a little, we were ready to chow and dig for bus fare.

So Friend A had a piece of pizza, got really big eyes during the bus ride (especially when a man in a wheelchair got on, and the huge mechanical ramp unfolded, and then the bus driver had to clip in his chair five different ways), and danced and jumped during the parade. At one point, when people on a float had tossed out candy, and all the other kids were unwrapping their suckers, Friend A turned to me, holding up a small mint, and asked, “Can I have this? It’s less than one carb, so I won’t need to dose.” Jokingly, as I told her yes, I said, “Honey, I sooo don’t have a grip on all this stuff; I have to believe anything you tell me.” Her immediate, vehement response was, “I. take. it. very. seriously.”

At that moment, it was all I could do not to hug the very breaf out of her body.

A few hours later, home, watching a movie, snacking, readying for bed, she checked her blood levels (“two-two-two,” she told me), called her mom, dosed herself, and ran, giggling, up the stairs. As I tucked her in, I admitted to her that I was nervous to come in and wake her up in a few hours: “First off, we have a household policy never to wake a sleeping child, but also, since you’re not my kid, and you’re not used to me in the night, I worry that you’re going to be scared when you wake up and think, ‘Hey, whose big face is hovering above me?’”

Friend A nodded and admitted, “I’m probably going to be mad at you, actually. Because I’m tired, I’m pretty mean when I get woken up for a night time check.”

“Hohboy,” I sighed back at her. “Well, how about this: if you’re really crabby when I wake you up, I’m going to start telling you things like how I’ll buy you a pony in the morning and then we’ll go get you some new roller blades and $500 worth of clothes at the mall, and then we’ll go to the waterpark, if only you’re nice to me?”

Having a complete bead on me, knowing I’m full of malarkey, Friend A grinned and said, “Deal.”

Thus, once the rustling sounds in the girls’ room ceased, the waiting began. Despite being outrageously tired from Paco’s recent nights of no sleep, I decided to stay up and noodle around for a few hours instead of going to bed and then having to drag my own cranky self out of it a few hours later. ‘Cause when you have to promise to buy yourself a pony, it doesn’t feel special at all.

At almost one a.m., I crept in, ready for battle. Juggling her meter and kit, a tupperware full of rice cakes, and a bag of glucose tablets, I prepared to stroke her hair until her angry eyes opened.

However, Friend A, keyed up by the unfamiliar situation, woke immediately; she sat up, shivering, and rubbed her eyes. “Okay, honey, here’s your stuff.”

With unimaginable efficiency, she stabbed her finger, failed to draw blood, lanced it again, squeezed, put the resultant drop onto the slide, inserted it into the meter, licked her bleeding finger, and waited for the number.

A big 63 popped up.

Even I knew “low” when I saw it; only the next day did I look up the technical definition of “hypoglycemic.” Immediately, Friend A said, “I have to eat something” and cracked into the rice cakes. Silent except for the crunching, we sat in the dark. “Now I need a tablet, too,” she announced, and continued chewing.

When she was done, I asked, “Hey, girlie? That was kind of a low number. Do you think I should check you again in a few hours?”

And here’s where she got me forever. The soft, sleepy, clinically-efficient nine-year-old in a sleeping bag responded, “I don’t know. Maybe you should call my mom.”

Certainly, the mom-to-mom phone call at 1 a.m. is no one’s favorite duty. Fortunately, Friend A’s mother is worthy of such a daughter and snapped to attention quickly. “Yes, that’s low. She needs to eat.” She did. “She needs to eat more. Do you have a granola bar? If you can get a granola bar into her, she’ll be fine ’til morning. Was she really crabby with you? She gets like that when she’s really low; her brain isn’t firing right, you know. ”

Yes, I had a granola bar. No, she hadn’t been the slightest bit crabby. Oh, holy Richard Simmons, but her brain had been firing just fine.

We decided that, in the middle of the night, when you’re nine and hypoglycemic, it’s sometimes best to hear from Mom that you need to eat more. After a quick phone conversation and goodbye, Friend A and I sat again in the darkness, listening to her munch.

After the last swallow, she plopped back down onto her pillow and cashed out. Moments later, head plopped onto my own pillow, I took a few minutes to consider

how there is something heroic–something that qualifies as “above and beyond”–in a kid who lives stoically with chronic illness,

how jaw-dropping it is to see matter-of-factness in a little person who doesn’t get to take her body for granted,

how much I respect that she doesn’t inveigh against her blood, her pancreas, or the fact that her innards have a notion to defeat her,

how resolute she will have to be for the rest of her life–even during her college years, when she moves away from home, when everyone around her is engaged in a season of purposeful neglect of schedules and health and accountability–to even have a rest of her life,

how she gets to be her own best hero,

how I no longer needed a VW van at sunset

because I had a date to go buy a pony at sunrise.

Leave a Reply