My head is muzzy, and I am out of sorts. I stayed up too late, lost in a compelling book, and then woke up too early, my brain–still full of images from the book–unable to rest.

My head hurts; my body is empty of energy. I have class in an hour. The idea of putting on clothes feels like too much. But I have to. I have class. Even when my head hurts, and my body feels flat, life chugs on.

In the midst of this haze, one thought thrums through me: I am outrageously fortunate. It is a misery of rain outside, but I am warm and dry. When I drag myself to the closet, I will be greeted by bountiful options. When I head to class, my stomach will be full. I will drive my cute little car to campus; I will reward myself later with a hot cup of coffee; I will close the door to my office and find peace as I grade journal entries; some hours later, I will stand in my kitchen, smelling dinner cook, surrounded by my family. Fueled by a feeling of security, I will cruise through my electricity-lit day, hours marked by protective walls, soft linens, ready laughter, rampant choices.

Although none of us is ever wholly guaranteed of continued safety, I inhabit life with an innate assurance that, relative to millions of people on the planet, I am safe. Balancing on the fingertip of Lake Superior, living in a modest city not apt to be drafted into making an international political point, I float along, minute to minute, unmolested.

I am intact. I have not earned this easy wholeness.

Chance. It’s all arbitrary chance.

As I type this, hyper-cognizant of my luck, I am not writing about the shootings and bombings in Paris —

although of course I am.

I am not writing about Lebanon or Nigeria or Ukraine or Cameroon or the Philippines or Libya or Pakistan or Israel or Tunisia or Afghanistan or the United States or Saudi Arabia or Somalia or Turkey or Mali or Yemen or Egypt or China or Kenya or India or Macedonia or Iraq or Chad or Syria or Kuwait or Niger or Bahrain or the West Bank or Bangladesh.

Although of course, of course, of course, of course I am.

Through the randomness of birth, I have enjoyed a felicitous existence. Certainly, all the good could literally explode in my face one day. Odds are, though, that I’ll continue to drive my cute little car and assemble outfits from a closet of too many clothes. I’ll whoop, happily, “I’m desperate for a piece of that warm bread, preferably slathered with butter.” I’ll toss off a thoughtless “When that student came after me and sent a Howler to my inbox, I desperately would have loved to hit reply and tell him a thing or two.” Brashly, I’ll announce, “I’m so desperate for sleep, I could put my head down right now and conk out for twelve hours.”

Such words are heedless of genuine desperation. In the toughest moments of my life, I haven’t trailed a single finger down the spine of desperation.

The compelling book that kept me up until 3 a.m. several nights in a row reminded me that my words and attitude are feckless. It reminded me that I know nothing of desperation. Its made-up story, all too real, hammered home that I have never stared, eyes full of tears, clutching my children to my hips — as though proximity to their mother could save them — at authentic hardship.

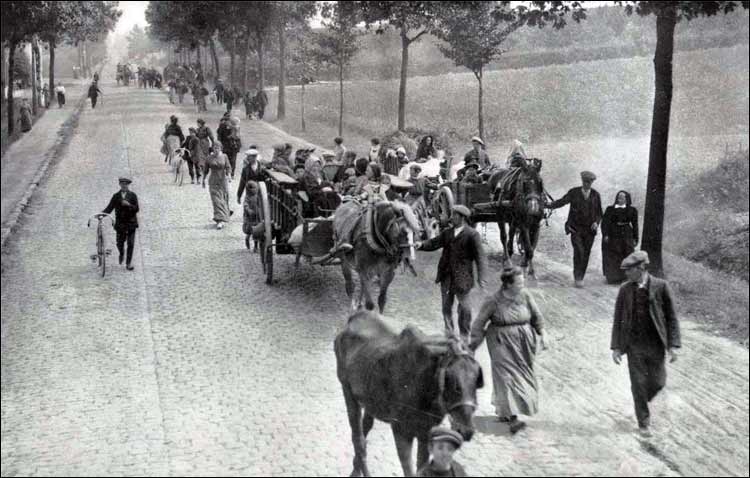

I don’t know what it feels like to have my husband taken from our home at gunpoint by strange men, to never see him again. I don’t know what it feels like to hunker down inside my home and cry to a faceless god as rockets land on my neighbors. I don’t know what it’s like to secret my children across borders, to bargain away the few things I carry just for a meal that leaves us hungry. I don’t know what it’s like to watch my children, whose legs still ache with growing pains, resort to lying, thieving, and trafficking in the name of staying alive.

I don’t know what it’s like not to bathe for weeks, to wear the same tattered clothes for months, to watch, breath-held, for an opportunity to squeeze through a hole in a fence. I don’t know what it’s like to press my body to the inside of a tunnel as a train blows past, two feet away. I don’t know what it’s like to load my children on a boat and hope the waves carry us to land, not eternal blackness. I don’t know what it’s like to be treated like inconsequential trash when I have been a respected teacher, a treasured friend, a valued citizen. I don’t know what it’s like to be invisible unless I express a need, at which point I materialize as vermin. I don’t know what it’s like to sprint from the authorities for daring to steal a chance at life.

I don’t know what it’s like to be saved by the small acts of kind strangers, each of them with their own stories of agony and loss.

I don’t know what it’s like to seek refuge, having been forced to abandon everything I have loved and known all my life.

I don’t know desperation.

The book, this book I have been reading until 3 a.m. for several nights, powerless to set it down until I know the fates of the characters, takes me inside desperation, creates in me the hard, dull knot of panic and fear that governs the life of the refugee. As I read, sliding up and down my pillows, attempting to keep the pin-prickles out of my arms, my stomach is tense. I am faintly nauseous. I love these people in this book, am part of their decimated family; I am willing their survival, flinching at the distaste with which decent, loving individuals are treated when they are battered by violence and take flight from it.

This book makes me want to shout at the world.

My bladder is full, but I cannot take a break until I know if the family’s forged papers, for which they paid too much of their too-little money, will get them from Kabul to Turkey to Greece to France to England. I have to know if they will find safe haven before the baby’s medicine runs out. I have to know if fourteen-year-old Saleem, taken into custody while pawning his mother’s wedding bracelets — her sole inheritance from her dead mother — will find his way after he is deported from Greece, one step backwards to Turkey. Will he manage to skitter to the undercarriage of a truck during the two seconds when the driver turns his back to light a cigarette, grabbing hold of its exhaust system before it rolls aboard a ferry to Greece? If he does, will his corpse be found on the floor of the ferry after he dies from inhaling carbon monoxide? If he dies, no one will ever know who he was. He will be a nameless fourteen-year-old, the sole support of his mother and siblings, the kid who still yearns for his murdered father, the sweet boy craving a taste of orange soda, dead in an unmarked hole.

How will his mother’s heart ever find rest, if her fourteen-year-old son is dead in an unmarked hole?

How can the world in this book, which is actually our real world, carry on as though this bright, devoted boy doesn’t matter, this teenager who ends up sleeping in door frames on a piece of cardboard, waking at night to find another desperate man holding him down, unbuckling his pants? How can this boy’s made-up story, all too real, too true, too common, possibly leave me untouched?

How can I sleep, use the bathroom, heed the burning of my eyelids, until I know if Saleem makes it, if Fereiba, his mother, will ever see him again?

How could anyone label the Fereibas and Saleems of the world, so heart-breakingly admirable in their simple desire to live securely, as “those horrible people”?

I am hungover with fatigue from this book. When I awake, my sleep too short, I feel coated by this story — jarringly intimate in its portrayal of the details of displacement. It is a fictionalization of everything most devastating in our world today.

These characters I have come to love are reflections of reality. On my campus, walking the same halls I walk, there is a Saleem, only his name is Gani, and he is not from Afghanistan. Born in Somalia, Gani’s life changed forever when he was five, when his father went out one day and never returned home. Time passed. Rumors floated in: Gani’s father had been caught between warring factions. He was dead. Fracturing under the pressure of waiting and uncertainty, increasingly fearful as bullets richocheted between buildings, Gani’s mother decided to gather her six children and flee to the refugee camps in Kenya. Walking, haggling for rides in caravans, taking weeks, mother and children moved away from the men with guns towards the camp with no hope. Each time they secured passage for the next leg of their journey, they had to leave something else behind. “There is room only for you; leave your bags.” Within a few days, Gani’s mother and siblings carried only a sack of sugar. Once a day, each child poured a mound of sugar into a cup. The mother added some water. This was their meal.

From there, Gani’s story gains momentum, from refugee camp to high school in Kenya to the resolute decision that he wanted his life to become more than scrabbling for the next meal. After landing in the United States, he worked, moved, worked, mastering English to the point that he became a translator and liaison for other immigrants. Working in a clinic as a technician and a translator, he decided to become a nurse. Now, on the verge of graduation from our college, Gani is the president of the Muslim Students Association; he serves on the Global Education committee; he answers phone calls at 1 a.m. from desperate Somalis who need his voice. When Gani related his life story in an intercultural group on our campus, he excused himself, midway, for a few minutes.

He did not go to the next room to arm a bomb. No. He was praying, thanking Allah for the many blessings of his life. Minutes later, his prayer rug tucked away, he returned to our group, picking up the thread of his narrative with “…and then, in Kenya, my mother opened a little store, selling t-shirts and candy and small things. She found that way to support us.”

In all my life, I have not met a finer person than Gani. He enriches everything around him, most markedly the country that accepted him. The United States would be a lesser place without him.

As I read my book at 3 a.m., I think of Gani, for he is in its pages.

Even more, the plot of the novel takes my memory back to a radical act of generosity I witnessed in 2011. At the time, as I watched it happening, I merely thought, “Well, that’s really nice.” Now, with my head so immersed in the events of this book, in the events unfolding around the globe, I am able to unpack its beauty more fully.

In 2011, our family spent many hours and many weeks seeking Turkish residency papers; we’d tired of worrying whether we could renew our 90-day tourist visas repeatedly. Because the process was lengthy and required us to interact with non-English-speaking officials, our friends Andus and Gulcan came to our aid. Again and again, they drove us to the government building in a neighboring city and sat with us, waiting. When it was our turn, Byron and Andus would go into an office with other men and discuss which papers still needed which signatures and who needed how much money. The kids and I would wait out on a bench with Gulcan, the only native Turkish speaker in our group.

One afternoon, as we sat in the waiting area, a multi-generational family arrived and took the bench next to us. After not too long, one member of the family, a stunning teenage girl, maybe 17 years old, engaged us in conversation with her limited English. Her family was fleeing Iran, seeking asylum in Turkey. They were Christian. When she learned we were from the United States, her eyes widened, and she asked, eagerly, “So you are Christian too?!!”

My answer was difficult to form, given the meager mutual vocabulary we shared. How to explain, “Uh, well, I was baptized in a Presbyterian church, and then, as I was growing up, my parents started attending a couple different Lutheran churches. Sure, I used to help my sister in the church nursery, and I did attend Sunday school, but by the time I was 14, I’d had enough of feeling, as I sat on a pew, that I was just woodenly going through the motions. So then I pretty much stopped attending, except sometimes. And for my husband, well, his parents were uncomfortable with religion, too, but felt obliged to make the effort, so he did end up getting confirmed…so, I mean, our cultural and familial histories involve Christianity, but where we both stand right now would be more fairly named agnosticism.” How to explain that to someone with fifty words of English?

I told her, “No, not really. Not really Christian.”

My response confounded her. If I lived in an historically Christian country and had the freedom to love Jesus publicly, how could I not?

There was something poignant in that moment as we stared at each other, her stunned, me sheepish, liking each other, both believing firmly in freedom of religion. It’s just that our definitions of that concept were drawn from different dictionaries.

Given no other option, we smiled at each other, shrugging, letting the moment brush past us. As I tried to ask her where her family was staying, it became apparent that they were trying to figure that out themselves. If they could get papers and gain legal recognition in Turkey, their options would expand dramatically. In the meantime, they were homeless, uncertain of their next steps.

And that’s when Gulcan, a fiery, unpredictable woman, someone who inspired in me a mixture of awe and fear, gave me a lesson for my lifetime. Jotting down some information on a scrap of paper, she looked the Iranian girl directly, meaningfully, in the eye and said, “My husband and I run an inn in the village named Goreme. It is called The Fairy Chimney Inn. If you can come to me, I will give you work. You can come to me, and I will help you.”

Bleary as I am, my defenses compromised due to book-induced lack of sleep, I cannot type those last words without crying.

So: there is this book I have been reading. It is not a great book — there are issues with structure I could address if it mattered here — but it is a book with greatness in it. It is a profound example of how a novel can teach readers about the unseen intricacies of the world around them.

The story in this book makes me keen for refugees, makes me want to hand a hungry person bread and cheese, makes it impossible for me to tolerate big-picture discussions based on the premise that “our country can only absorb so many.” Everything in the stories of Saleem and Fereiba and Gani and the Iranian family reminds me that I am so, so, so damn lucky, reminds me that there is no such thing as “those people” because we are all of us, together, the people. This book illustrates completely that we are wrong to say “us,” and we are wrong to say “them.”

There is only us, a single us, and we should extend our hands towards each other.

Always and forever, it is one person with helping one person without that saves us all.

This book that I have been reading until too late — sliding up and down the pillows, trying to keep the prickles out of my arms, watching storytelling transmute abstract into concrete, marveling at how fiction tells the truest stories — is Nadia Hashimi’s When the Moon Is Low.

My brain is muzzy, my heartbeat unsteady. I am exhausted.

And, oh, so fortunate.

—————————————————

Leave a Reply