This is the story of a student, and this is the story of a teacher.

You will want something heartwarming, uplifting, and transformative.

Perhaps this is not that.

***

At the end of January 2018, I returned from five months of living and teaching in the country of Belarus where I was a Fulbright Scholar. For those months, I left my family in the United States and went by myself on a grand adventure.

Belarus is a country about the size of the state of Kansas, with a population of roughly nine-and-a-half million people. The president has held office since 1994, and that is the reason why Belarus, more closely aligned with Russia than any other former Soviet republic, is also known as “Europe’s last dictatorship.”

Although I had sought this opportunity and was ready to say “yes” to everything, the truth was: for me to go on this Fulbright, to relocate to the city of Polotsk near the Russian border – for me to rent an apartment and throw myself into untested professional waters – this was something much more than a grand adventure.

It was a chance to see who I was when untethered from all I’d carefully cultivated over decades.

***

In my new city, I taught at several locations, and I taught different groups of students, but one of my main duties every week was to teach at Polotsk State University. At the university, every Tuesday, I was scheduled for two 80-minute classes back-to-back. The first class was fifth-year students (the undergraduate degree path in Belarus is a five-year course, so the fifth-year students were in their final year); these students were charming, dedicated, delightful.

After their 80-minute class, the next class was fourth-year students. There was some confusion with the enrollment for this class, and it ended up that I taught two different groups of fourth-year students who alternated every other week, setting up a rotation where I would see each group of students once every two weeks.

The fourth-year students were messier than the fifth-year students. Perhaps it was because their schedule was somewhat irregular, or perhaps it was because I was teaching to them a class that had never been heard of or seen in their curriculum before. With the fifth-year students, I was teaching a customary class, Extensive Reading, in which we read and discussed American short stories.

But for the fourth-year students, I had proposed to teach a class I had developed in the United States called Writing for Social Media. We thought the students would love this. The students thought they would love this. Maybe the students loved it.

It was hard to tell.

The fourth-year students excelled at absenteeism, attended infrequently, and often didn’t turn in work. It felt like I was teaching at my home college, in some ways.

But when those fourth-year students did attend class, they were a joy. When they were in the classroom, they were attentive, fun, and energetic. When those faces were in front of me, I forgot how ineffective I felt in their absence.

It’s important to note: when it comes to any kind of teaching, I’m high-strung and anxious. I don’t sleep well when I know I will be heading into a classroom. Most definitely, I don’t cruise into the place tossing candy out of a top hat. Rather, I spend significant agitated time in the bathroom as the minutes to the class period tick down.

When put into a new situation, such as teaching in a country like closed-off Belarus, my nerves were even more heightened.

As a result, every Tuesday, when my two back-to-back classes were finished, I felt a rush of endorphins, a glorious and sweet relief that exhaled, “Whew, I did it!” As celebration, once the students had departed, I would run to the bathroom down the hall for another kind of exhale.

Most Belarusian universities and public places are equipped solely with squat toilets. No toilet paper is provided, nor is soap, towels, hand dryers, or hot water. This spartan approach is at odds with the effort that goes into personal appearance. In Belarus, everybody is turned out – as a rule, Belarusians look chic, they look crisp, and they own irons. I was trying to keep up, so when I taught, I wore fancy shoes. Thus, even though I was flooded with relief that I’d made it through my classes – YES! – I still had to navigate the pedestal squat toilet – two steps up — in high heels for the after-class exhalation.

***

One particular day, I’d had my trip to the toilet and returned to the classroom to wait for the next teacher to arrive so I could hand off the key. Sometimes she showed up ten minutes, even twenty minutes, into her class period – she had tea to drink in the faculty office, gossip to catch up on, or questions from the “professor of the professors” to answer regarding her dissertation. Her students didn’t mind; they were perhaps happier to see me than her – because, again, Belarus had been so closed off from Westerners that in this city of Polotsk, with a population of 90,000, and in the neighboring city of Novopolotsk, with a population of over 100,000, I was the only native speaker of English. For those who’d spend years studying the language, my presence was a chance to experience authenticity.

On this particular Tuesday after I’d been to the toilet, I was hanging out in the hallway, waiting for Vera, the teacher of the next class. I loved to hang out in the hall and watch the university students in their native habitat, but I also loved to linger there because into the wall outside my classroom was embedded a cannonball from 1812, from one of the times Napoleon’s troops had invaded Polotsk. I liked to stand there by the door outside my classroom, leaning, resting my hand on the cannonball, rubbing it and thinking, “When else in life will I be able to casually stroke a cannonball?”

On this day, as the cannonball and I were hanging out, I heard a voice come at me from over my right shoulder. “Excuse me. I have a problem.”

It was one of my fourth-year students; I wasn’t quite sure what her name was yet. When it comes to names in Belarus, as in Russia, there are a lot of Nastyas, a lot of Dashas, a lot of Elenas, Irynas, Alionas, with occasional Sonyas for variety. But with this student, I couldn’t think of her name even though she was standing in front of me, telling me “I have a problem.”

Then, in a flash, I remembered: Yana. Her name is Yana. This is the Russian diminutive of Johanna. Yana.

Relief flooding me, I said, “Oh, Yana, yes. What is your problem?”

Inside myself, I was braced and nervous. When a student comes up to a teacher and announces “I have a problem,” the words send a gong of doom ringing through the teacher’s skull.

In very broken English, she communicated, “I need help. My English no good. I need help. You have time for me?”

At this point of my experience in Belarus, I was constantly overwhelmed. As the only native English speaker in the area, I was a kind of celebrity. I was teaching my classes at the university; another day each week I was teaching at the language center in a nearby city; another day of the week I was volunteering at a gymnasium with high school students who were training for a Language Olympiad. When I would leave my apartment or walk home from campus, I would be chased by Belarusian English teachers who would breathlessly ask, “Next Wednesday, could you come to two of my classes, 80-minutes each, with second-year students, and talk on the topic of Travel? A slideshow would be very interesting.” Or another time, “Could you come do two 80-minute classes with my first-year students? We’ll try out a round table discussion on the subject of The Intersection of Culture and Colors.”

Even more, I went to fitness and yoga classes, and every time I left the studio, there would be two or three women wanting to walk me home – to practice their English. The ten-minute walk could take thirty. Sometimes it ended in someone’s home, with tea and cake and photographs.

Absolutely, I was overwhelmed by the enthusiastic attention that alternated with days of drifty loneliness. Whereas my life in the U.S. has a steady, predictable pace to it, Belarus was a study in extremes. Indeed, when Yana said, “Do you have time for me?” I felt an internal panic, a scream rising. What I wanted to say was, “NOOOOOOOOO, PUBLIC INTERACTIONS EXHAUST ME; MY COUCH AND I NEED MORE MOPING TIME!”

But still. She was a student. And I was her teacher.

Of course, the answer was “Yes, I have time for you.”

***

We arranged to meet the next week in the square in the middle of the city where there’s a big fountain. It was October, and the water was piping. Kids after school were playing in the fountain as their parents and grandparents hovered nearby.

Yana and I had decided we would sit on a bench and just talk to each other so she could practice her conversational English. On that gorgeous October day – that kind of October day when the sunlight is slanting sideways, and the whole world seems like it’s glowing, the leaves skittering across cobblestones – on that kind of October day, Yana and I sat for two hours on a bench, chatting and watching kids play.

I knew for this to be helpful time for Yana, I shouldn’t be the one talking. Rather, I needed to get her talking. I went for the easiest possible opener: “Tell me your life story.”

Yana began with the fact that she was from a small village about an hour outside of Polotsk, and her coming to the university was an achievement for her family and her village. She loved her parents, her sister, her older brother, their spouses, her nieces, her nephew. She was devoted to the kids and would help them every day with their homework and play games with them. Her family was her life.

Jumping to important life events, she rewound three years, disclosing, “My head start hurting. Bad head hurt. I no okay.” She went to a doctor, then a lot of doctors, and after many exams they discovered that Yana, at the age of 21, had a brain tumor.

It was difficult for me to find out all the small details of Yana’s medical journey because her English vocabulary was limited. When I asked her, “Did you have surgery?” she looked at me blankly. I tried “Operation?”

She got that one. “Yes, yes.”

I followed up with “Cancer?”

She knew that word. “No, no, no. It okay. I was okay.”

“It was benign?” I clarified.

“It was okay.”

Then she made it clear she had many treatments after her surgery, the aftereffects of which were that she had debilitating headaches still, but she also fell into a kind of depression, suffering from cognitive challenges that made her flat, grey, nonfunctional.

During this time, she dropped out from the university; stuck in darkness, she couldn’t handle being a student. For the next three years, Yana stayed in her bedroom in her parents’ house in the village. The only person she would speak to, the only person she would allow into her bedroom, was her mother.

Every day, her mother would bring in food and try to cajole her. She’d bring in the little nieces and the nephew. Desperately, she tried anything, everything, her every effort asking, “Can we bring Yana back to life?”

Always, Yana refused every overture. Every day was NO.

It got so bad that Yana was hospitalized. There under the October sun, kids splashing nearby, she haltingly explained, “They take me…asylum. Asylum. One month. Bad place. I believe asylum…horrors. Asylum worst place in the world.”

I decided not to press for details on those horrors, but my takeaway from those two hours on the bench was that Yana was different. In Belarus, you don’t see a whole lot of different.

After Yana was released from the asylum, something inside her flipped. She decided, “I’m going to rejoin the world. I’m going to re-engage.”

Bravely, tipping towards the light, she walked out of her bedroom and out of her house. She returned to the university.

When I saw her that fall in my classroom as a fourth-year student, I hadn’t realized it was the first time she’d set foot on the university campus in over three years. I hadn’t realized that when she was sitting in my Writing for Social Media class, she was returning to the world of the living.

As we talked on the bench that October day, she said to me, glowing like the autumn sun, “Now, I fine. No stresses, no pressures, no problems. I look my classmates, these girls, hair, make-up, boots, boyfriends, all look same. Me? I not same. I fine. Nothing bother me.”

***

After that day on the bench, Yana and I agreed to meet again two weeks later. By that point, the weather had changed; stark and windy, November helped us decide to meet at a coffee shop.

Again, we spent two hours together. Contemplating how to fill the time, I had been intimidated, thinking, “She pretty much gave me everything that first day. I don’t know what we’re going to talk about.” Punting, I packed some games into a bag.

As we sat down at a table with our lattes, I asked her if she knew the phrase “to be a guinea pig.” No, she did not. I explained the idiom and told her she was my guinea pig with these games because I wanted to know if they would work for non-native English speakers.

Yana’s eyes got big when I pulled out Bananagrams.

For two hours, we sat there, starting off easy and slow – “We don’t have to play by the rules,” I told her, spreading out the tiles. “Just take some tiles and try to put together words in English. I’ll help you. Can you see some words there?”

Oh, yeah, she nodded. Uh-huh. She could see some words there.

Upping the difficulty, I pressed, “Can you link some words together, like in a crossword?”

Sure. Okay. Uh-huh. Uh-huh. Yana nodded and moved tiles.

Then she got quiet. Her head was down. As she slid more tiles in front of her, I realized she was improvising her own variation of the game.

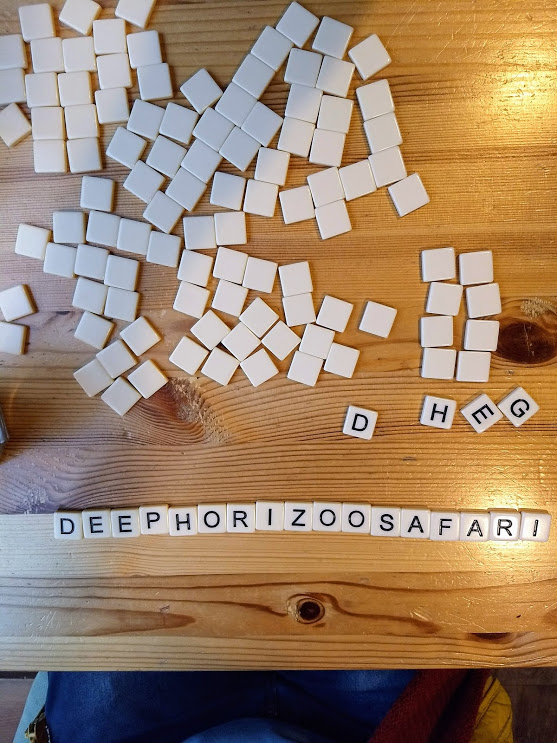

She had spelled the word deep.

To its end, she had attached the word horizon.

She’d seen the movie.

Her eyes continuously scanning the tiles, she told me, “I want put more after horizon. What I do?”

“Well,” I mused, “horizon could become the word horizontal if we add some letters on the end…”

Yana’s eyes brightened, and before I quite knew what was happening, we were launched into a version of Bananagrams that involved the creation of compound words and portmanteaus and strings of overlapping text.

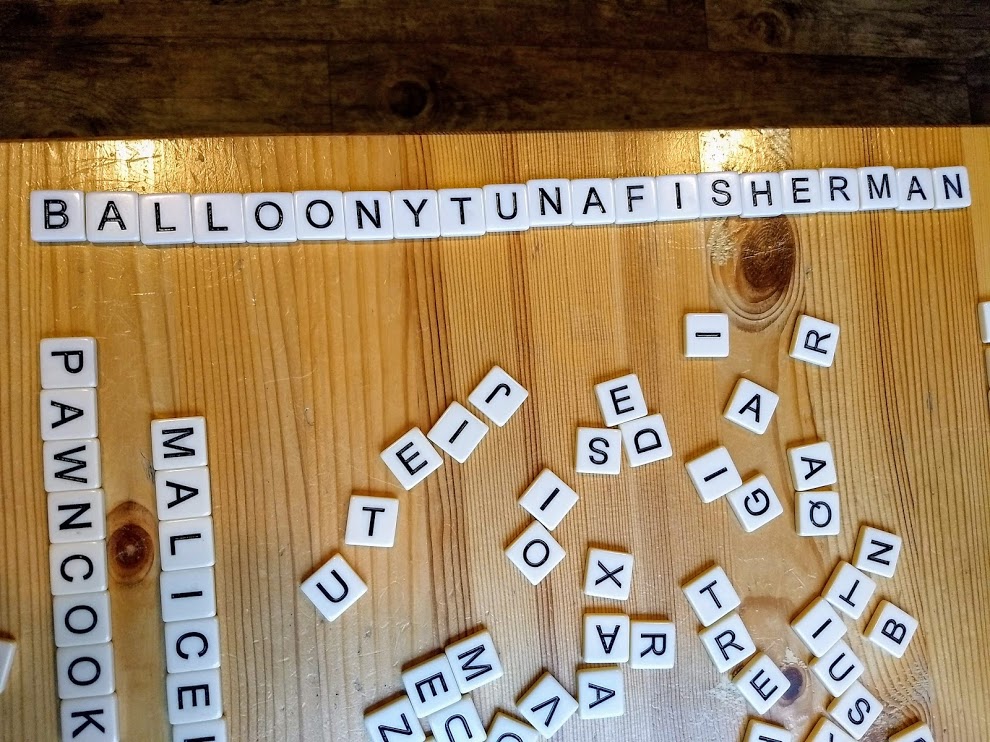

Having run out of space with deephorizoosafari, Yana started a new line with balloon, asking, “Hmm, what I do? I want add more.”

Looking at the word, I suggested, “Well, if you add a -y, you’ll have the word loony growing out of balloon. We have this cartoon in the United States, Loony Tunes, that’s really famous; do you know it?”

No.

I explained Bugs Bunny and Sylvester the Cat and Tweety Bird. Then we added letters to make: balloonytunes. Excitedly, we kept the growing word evolving – adding, re-spelling, shifting – “Ah, how about tuna? Tuna is a kind of fish!”

Placing the letters on the end of the growing word, Yana read aloud, “Balloonytunafish…what I add?”

“What’s the word for a person who takes a rod and a line and stands in the river trying to catch fish?” I challenged her, miming my description.

“Fisherman!” Yana yelped. “Balloonytunafisherman!”

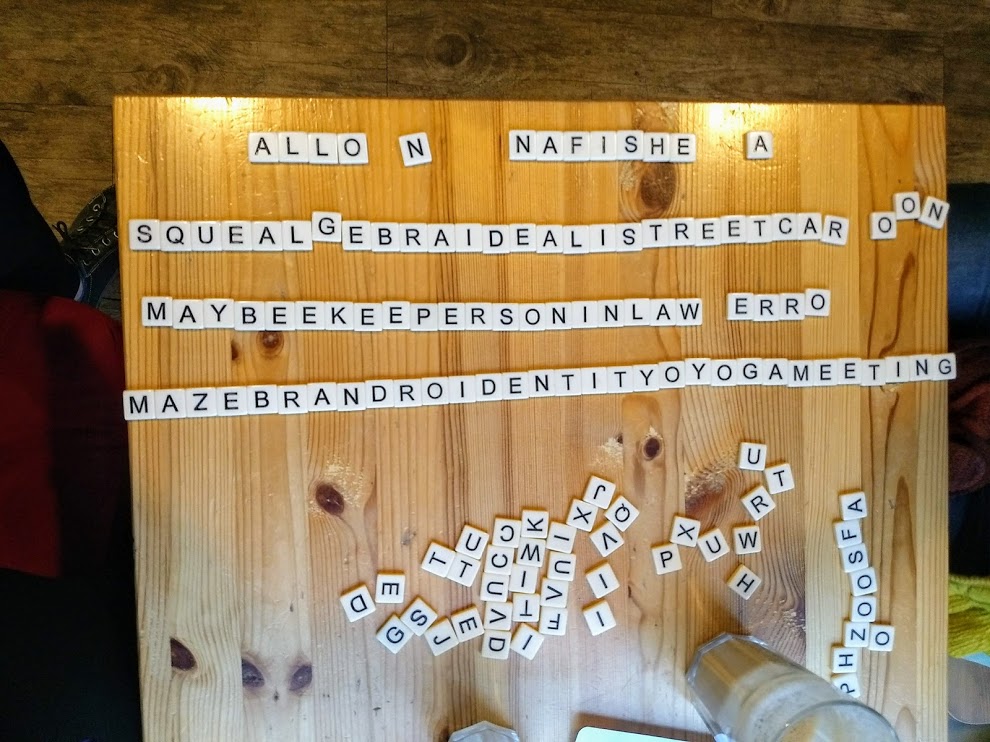

Starting a new word, her brain churning as she tried to figure out the spelling, Yana came up with squeal. Immediately, mind-bogglingly, she saw a word to attach: algebra.

Her hands restless on the table, picking up letters, considering, discarding, she kept going. I helped her with vocabulary and spelling, but she was a firecracker. For an hour and a half, we strung together words.

Before we finished, I realized something important.

I was watching this young woman, so excited, so involved, this same woman who had spent three years in her bedroom, refusing to speak to anyone but her mother – and this young woman was lighting up the space around her in a coffee shop, stringing together letters, enjoying the burble of her brain. She was happy. She was excited. She was pipping.

Clocking the wonder of transformation, I marveled: “Her English is not limited. She does not have ‘a problem.’ Yana’s English is amazing.”

***

After Yana and I met those two times, she tried to schedule more meetings.

Each time, she had to cancel. She had to go to the doctor. Another time, her class schedule changed for the day, so I got messages from her, begging off. “I can’t come. I’m sorry. I can’t come.”

In terms of our class together, her group met with me seven times. Of those seven classes, Yana attended three. Her group was to submit to me five written assignments. At the end, Yana had turned in two.

In terms of the classroom, Yana was terrible. And I felt like a terrible teacher.

So.

This is the story of a student, and this is the story of a teacher.

You will want something heartwarming, uplifting, and transformative.

Perhaps this is not that.

***

But.

***

At the end of our conversation that first day under the October sunlight when we sat on the bench and watched the kids play in the fountain, I said to Yana, “I am so happy we had this time together. I am so happy we had one-on-one time, and now I know more about you. As soon as I get home, I’m going to message my husband back in the United States, and I’m going to tell him all about you.”

In return, Yana beamed. “As soon as I leave, I send messages and do phone calls. My family in village, they wait. They know I am meet you. My family know this first time my life I speak with foreigner. They wait hear me. When I call, I tell them – “

her words cracked me open, made me need a kleenexboyfriendshiplollypop, bestowed a benediction upon five months of lonely, exhausting, untethered, gratifying, glorious, unimaginable adventure –

“When I call, I tell them, ‘The English teacher from America, she make me most happy I can be.’”

Damn. I grabbed her for a squeeze.

And then we turned our faces in opposite directions to begin the trek to our respective homes.

Slowly, deliberately, contentedly, we walked away from each other, two changed people, forever connected.

***

This story was first told at the Gag Me with a Spoon community storyshare. If you’d like to hear it spoken: https://www.listennotes.com/podcasts/gag-me-with-a-spoon/perhaps-this-is-not-that-HKjLDkc76TO/#edit

Yana gave me permission to write about her, in case you feel your panties getting bundled.

________________________________

Leave a Reply