A prompt for today’s post:

Recently, the chief curator at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City rejected the White House’s request to loan Vincent van Gogh’s Landscape With Snow painting, instead offering to lend Maurizio Cattelan’s functional, solid gold toilet sculpture titled America. If you could borrow any work of art from a museum or collection in the world, what would you choose?

First off, I giggle at the Guggenheim’s statement in counter-offering the gold toilet sculpture to the Trump White House.

Beyond that, well, this prompt got me thinking for days. Coincidentally, just after I started compiling thoughts and ideas about the art that appeals to me to the point that I’d like to have it in my house for an extended period, the Obamas’ official portraits were released. I am not going to ask for either of those portraits on loan, though, as a huge part of their importance is having those powerful black faces — created by black artists — hanging in public spaces.

Sooooo…if I could have some art on loan, what might I request?

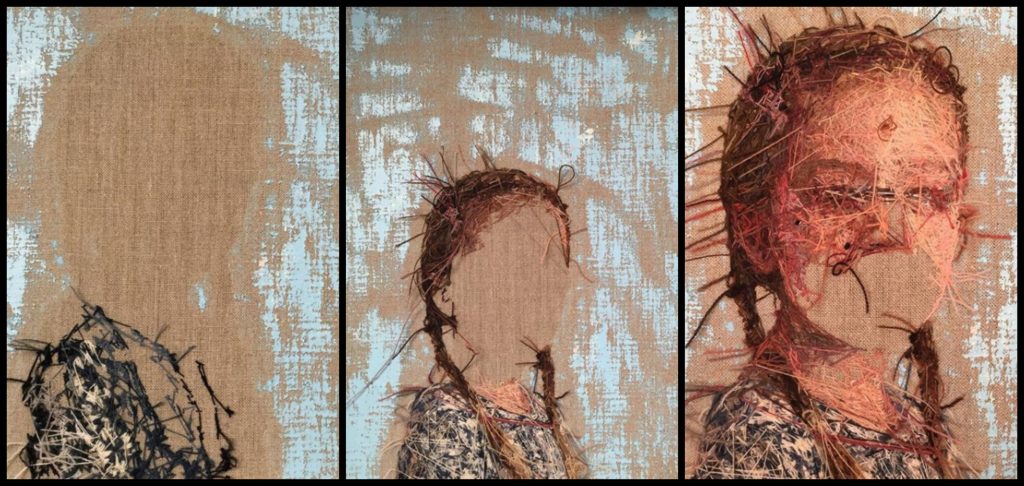

Immediately after I started pondering this question, I knew a couple of things: I tend to favor close-up portraits of people’s faces, and I am partial to textiles and fiber arts. Of course, my taste is not limited to these things, but my heart does thump visibly in my sternum for them, which explains why the first artist to come to mind was Cayce Zavaglia, whose portraits of friends and family give life to my Instagram, whose embroidery technique stops all my traffic, whose display of the “verso” of each piece serves as a metaphor for what it is to be human. An article published by Studio International notes:

The artist’s proclivity for portraying people she trusts as beautiful, strong and timeless found a counterpart in the embroideries’ reverse, where facial features become obscured by unwanted threads and knots. Zavaglia found an inspiring metaphor in the discovery of this reverse image, as it indicates, for her, the unseen and unpolished side of the human psyche. Apart from opening up the reverse side of her embroidered paintings to the viewer by displaying them on stands in the manner of sculpture, Zavaglia also found a way back to painting by focusing on this reverse side and documenting it in her hyperrealistic style in various stages of completion.

My first possible request, then, would be anything by Cayce Zavaglia.

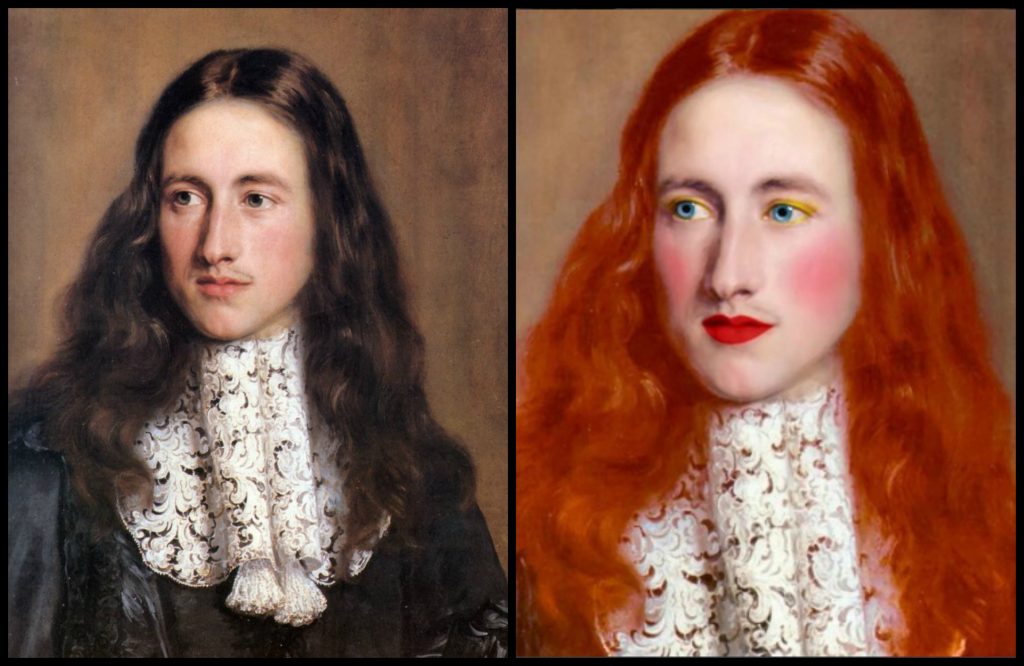

Zavaglia’s Instagram account not only features her work in progress, it also includes images of her current inspirations as an artist. A few months ago, she posted the image below on the right, of a red-haired dandy, which leads me to my next possible choice of a loan. That portrait of a wealthy, privileged man — yet clearly altered so that the colors and his appearance are jacked up — will not leave my head. Zavaglia’s commenters identified the 17th C. original from which the red-head was drawn: Portrait of a Young Man of the Chigi Family by Jacob Ferdinand Voet, which you see below on the left.

So Zavaglia was inspired by the jacked-up portrait, which was done by a disabled artist named Terri Bowden, and Bowden based her work on the original done by Voet, and, well, the whole business of art paying itself forward feels right and just. A blog named Disparate Minds explains Bowden’s approach thusly:

In her boldly marked drawings, Terri Bowden portrays…figures as if they are intense, strikingly present memories – fleshy and visceral in some aspects, but broadly summarized, distorted, and surreal in others. Faces are rendered with a realism and clarity that evokes vulnerability, re-contextualizing familiar icons of distant pop culture with a mysterious, untold narrative.

It’s the business of “re-contextualizing familiar icons of distant pop culture” that comes across strongly for me in the red-haired Chigi portrait. That dandy in Bowden’s painting is club-ready — his colors vivid and unreal in a way that makes me feel like I want to get dizzy under a disco ball with him.

In other words, I wouldn’t mind that face hanging on the wall in the living room.

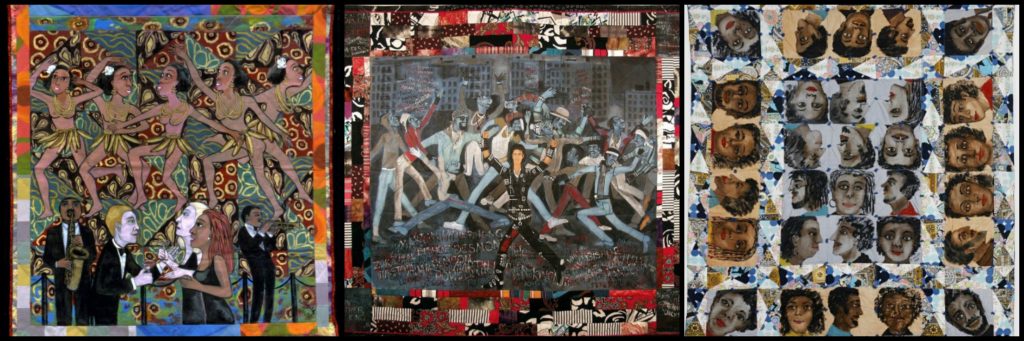

Also arresting to my eyes are the narrative quilts of Faith Ringgold, best known as the author of the children’s book Tar Beach. On her website, there is an FAQ section; one of my favorite moments on that page is this:

Do you do all your books on the criticism of black people?

Like all artists and writers, I am both enriched and limited by what I know and have experienced. In other words my books and my art are based on my life’s experience. I am, as you know, a black woman in America.

I also appreciate this overview of her work and views, as explained on Artsy:

A fervent civil rights and gender equality activist, Faith Ringgold has produced an inherently political oeuvre. In the early 1970s, she abandoned traditional oils for painting in acrylic on unstretched canvas with fabric borders, a technique evoking Tibetan thangkas (silk paintings with embroidery). The painted narrative quilts for which Ringgold is best known grew out of these early paintings, and denounce racism and discrimination with their subject matter. Combining quilt making, genre painting, and story telling through images and hand-written texts, the series “The American Collection” (1997) endeavors to rewrite African American art history, emphasizing the importance of family, roots, and artistic collaboration. In addition to demonstrating against the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney over what she perceives to be their exclusion of black and female artists, Ringgold has co-founded groups to support these demographics.

Below, you can see a few options that I would weigh, were I to request a loan of one of Ringgold’s quilts. On the left is Josephine Baker’s Bananas, in the middle is Who’s Bad?, and on the right is Echoes of Harlem.

Another possible request for a loan might be this next piece, Trolleyed, by Debbie Smyth, whose work is described as “statement thread drawings” by Thread Week:

…these playful yet sophisticated contemporary artworks are created by stretching a network of threads between accurately plotted pins. Her work beautifully blurs the boundaries between fine art drawings and textile art, flat and 3D work, illustration and embroidery, literally lifting the drawn line off the page in a series of “pin and thread” drawings.

The mixture of strong lines with messy ends feels a bit like looking in a mirror, to be honest. That this work manages to be both complicated and spare is another achievement I appreciate in all arts. Capping off my positive reaction to this shopping cart is that it’s an everyday thing — not some fancy 17th C. dude ready to go to the club but, rather, an item we all have touched, pushed, and used for its practicality. I look at Smyth’s cart, and it feels familiar; it feels tangled; it feels real; it feels fanciful. It feels like it should come hang on my kitchen wall.

Okay, the next contender for a letter from Jocelyn that opens with “Dear Artist I Admire: Could I show up with a pick-up truck and tote off one of your pieces…” is a Ghaniain man named El Anatsui who is, according to the Jack Shainman gallery:

well-known for large scale sculpture composed of thousands of folded and crumpled pieces of metal sourced from local alcohol recycling stations and bound together with copper wire. These intricate works, which can grow to be massive in scale, are both luminous and weighty, meticulously fabricated yet malleable.

Anatsui’s works feel like chain mail quilts, and I’m pretty sure I should hang one next to the bed so that I have something to look at when I can’t sleep at 4 a.m.

Awwwright, with these next ones, I’m going straight-on classic as I consider borrowing the paintings of Artemisia Gentileschi. Even though she produced in the 17th C., the controlled, bloodthirsty female rage in Judith Slaying Holofernes, Jael and Sisera, and Salome with the Head of John the Baptist feels pointedly relevant in today’s #metoo watershed, particularly if the paintings are viewed as a kind of autobiography — in which Gentileschi has painted herself as the murdering female exacting vengeance upon her abuser. Famously, Gentileschi was raped by a teacher/mentor, and if you’d like to know what that guy looked like, take a gander at the face of Holofernes, bleeding out on the bed.

I like this article in The Guardian that asks:

Artemisia Gentileschi turned the horrors of her own life – repression, injustice, rape – into brutal biblical paintings that were also a war cry for oppressed women. Why has her extraordinary genius been overlooked?

Again coincidentally, I had collaged these three paintings the day before the Obama portraits were unveiled, a day before Twitter erupted with opinions and tweets about every last detail, including outrage (from some) that one of the artists, Kehinde Wiley, has previously painted images of black women holding the severed heads of white women. In some beautiful Twitter moments, swells of art lovers directed the outraged to some basic art history — including various iterations of Judith slaying Holofernes — and explained to those who can’t fathom why a black woman holding a white woman’s head is a powerful fucking statement and not just “awful” that there is this thing where artistic pieces resonate over hundreds of years, and artists reference previous works in a way that adds layers to their new creations. I also appreciated those who posted art works in which black people are abused, dismembered, lynched, murdered, and oppressed and asked where the outrage had been when they were produced.

In summary: I am newly passionate about Artemisia Gentileschi because Trump is president, black lives matter, and sexual assault is no longer cause for a woman to feel she is at fault. COME TO ME, ARTEMISIA. I’d like to hang your work in the home of a woman I know who told her daughter “You made that all up” when she read her girl’s written account of the sexual harrassments she has experienced during her lifetime.

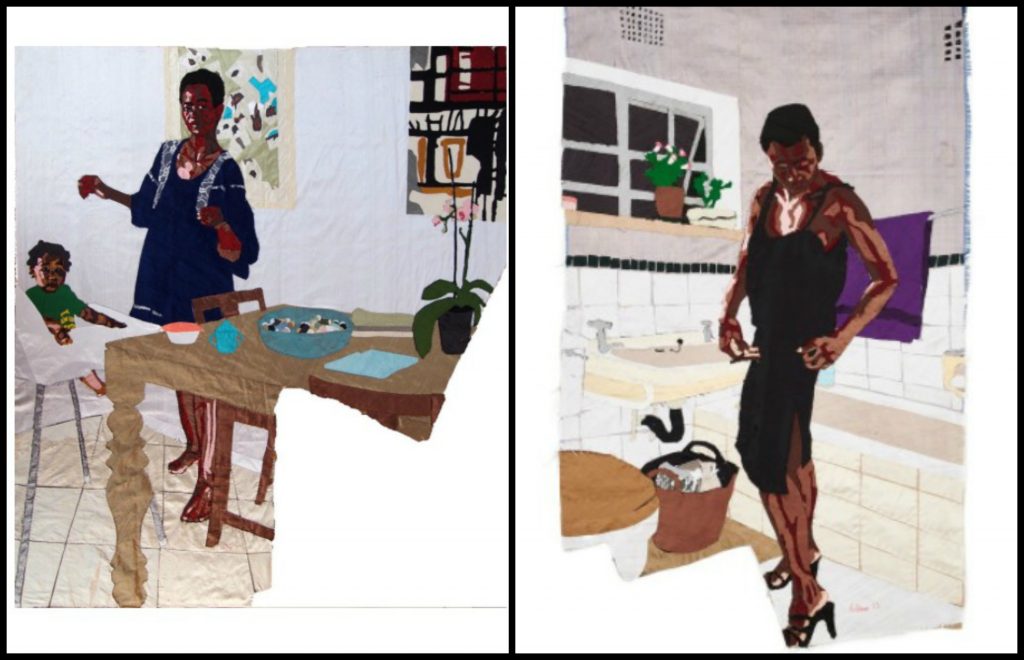

Now that I’ve been crabby about mothers who have internalized misogyny to the point that they are unable to be allies to their daughters, can we look at more quilts? The story quilts made by Malawian Billie Zangewa literally center a black woman, and they do it in a way that’s intimate, real, and human, focusing as they do on frozen moments from the artist’s life. In a quilt hanging in a museum (OR MY HALLWAY), do I want to see kitchen appliances plugged into an outlet? Yes, yes, I do. Do I want to see the pipe running from the artist’s bathroom sink in one of her pieces? Yes, yes, I do.

An article from True Africa provides more insights into Zangewa and what she does:

You do all your own stitching for your intricate silk tapestries. Can you tell us about the process?

I start off with an experience that elicits an emotion. The emotion then inspires an image that examines and narrates the experience. From here I do my visual research and then the template drawing. This is followed by cutting and pinning and then finally, the sewing.

It’s a very lengthy process and it all has to come together in the drawing phase otherwise I experience problems later on in the process. I have also learnt to allow my intuition to tell me what order things must be cut and pinned in. Previously, I would go from left to right or visa versa but the intuitive approach is more exciting and rewarding.

There’s been a lot of discussion on representation of black women in arts and culture. Do you find it empowering to portray yourself in your work as an African and black woman?

Absolutely. I am using my own image and body to tell my story. What could be more empowering than that?

Fortunately, my house has endless capacity when it comes to space on the walls for great art, which means I would like to borrow at least ten portraits painted by Missoula artist Tim Nielson (who also happens to be a friend, so you fuck wid him, you fuck wid me), filling all remaining hanging space with his vigorous, glorious, no-bullshittery patterns and shadows. If you follow him on Facebook, you’ll see that Tim chooses to paint people who deserve greater representation, and, truth be told, many times I don’t initially know the histories of his subjects. Fortunately, researching them teaches me much and gets my head to a place where I can start to see how Florynce Kennedy, Emma Goldman, John Brown, and St. James Hampton, for instance, are interrelated contributors to vision, activism, and constructive anarchy.

With Tim’s portraits filling my house, I’d have to shout at least once a day, “OKAY, BITCHES, LET’S OVERTHROW SOME SHIT!”

While my yells might scare the neighbors during windows-open season, who knows: some of them might get inspired.

And before you know it, look.

Something happened.

Art changed the world.

Leave a Reply