His grunting is muffled, but still, every “oof” and muttered curse can be heard in the hallway where his wife and I are stifling our laughter.

She speaks a few words of English, and I have a smidgen of tatty Russian, but we don’t need language to share a giggle, especially when it’s about the man in the bathroom grubbing around on his belly beneath the sink, frustrated and grumbling.

Every twenty seconds or so, we hear a cranky clank as my landlord tries to remove and then replace the metal vent covering the water meter. It’s October 1st, and, in addition to stopping by to collect the rent, he’s taking pictures of the numbers on various meters around my apartment so as to gauge the cost of utilities.

Getting to the bathroom meter, though — it just might defeat the best efforts of even Slava, a man whose tattoos and bald head convey an initial impression of undauntable toughness. There’s a truism about metal wall covers, however: they’re indifferent to tattoos.

To our credit, Slava’s wife and I weather the grunts straight-faced for at least three minutes before, eyes locking, we throw fists to lips and start shaking. I don’t know for sure what Slava is threatening down there on the floor, but his mumbles telegraph “FFS” effectively. Part of me wants to peek through the partially closed door, just to see if his track pants are slipping at all. I’ve never seen Belarusian plumber’s crack before, and I do so hate to miss a cultural moment.

But no. If I peer through the door, and Slava looks up at that moment, it’ll just irk him further, and then I’ll have to type some sheepish words into Google Translate and jam my phone towards his face down there under the sink. Better I just hover in the foyer with his wife.

THERE. In concert with three slams and six curses, the shadows in the bathroom shift as Slava stands up. I hope he’s not too worked up — because next he’s going to look at the faulty microwave and try to determine why it works fine for a few minutes and then taps out for ten hours. Since I need to type the particulars of the microwave’s moods into the translation app and coordinate a technology-assisted conversation, I want him calm and collected.

I scare easily, see, and I’d rather have no microwave at all than get yelled at.

Fortunately, Slava’s face, as he comes out of the bathroom, is full of good humor. It always is.

***

From the day I arrived in Polotsk and looked at apartments, Slava’s charmed me. When the women from the international center at the university and I first followed him up the crumbling stairs of the building and waited for him to unlock the possible rental, we had no idea what glories awaited us inside. We had no idea the apartment we were about to see had been the first place Slava bought for himself — ten years ago, when he was burning to create the perfect bachelor pad. As he remodeled his new purchase to showcase his tastes and sense of self, the driving motto seemed to be “Only the Best.”

“Only the best” is, it turns out, a uniquely individual expression.

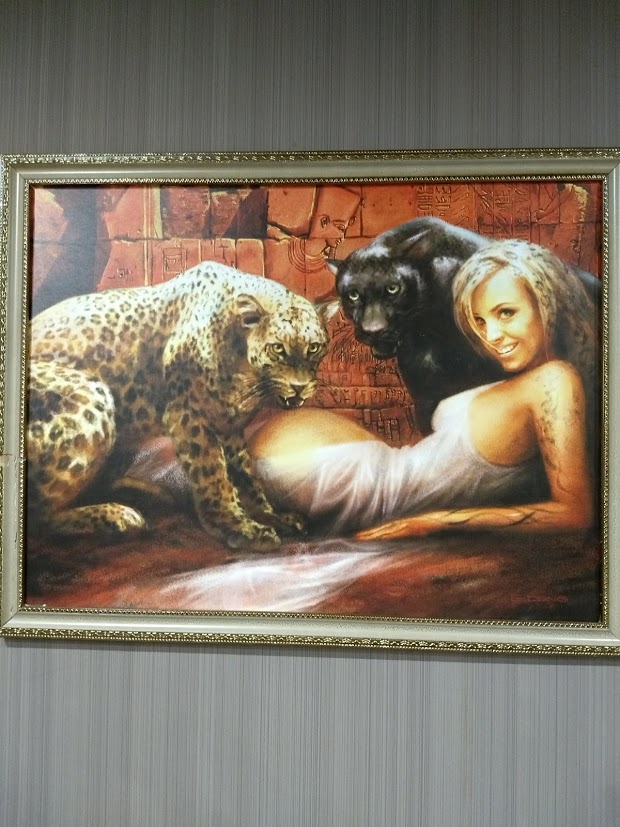

I didn’t know, that first day when I walked into Slava’s former bachelor pad, if I was allowed to raise my eyebrows, make a face, have a laugh. I didn’t know if what I was seeing was representative of Belarusian decor, as a rule. The women with me were properly respectful, definitely awed as they looked up at the massive Sad Angel mural spanning the ceiling of the living room, so I tried to follow suit.

As they asked questions and established a feeling of connection, I poked around the apartment, amazed at the sheer number of distinctive touches that revealed the interior of a man who initially read, to my gaze, as “thuggish.”

But then, every time I stopped peeking into the closet, taking stock of the washing machine, and wondering at the bright pink flowery rugs in the bathroom — every time I slowed my roll and looked at Slava — I saw the truth of him there, in his eyes.

This guy was sweet like a chocolate lab. It was all I could do not to pet his head and scruffle him about the ears.

Slava was all right.

Without question, I took the apartment.

***

It’s at the end of my first month under Sad Angel that Slava and his wife stop by to check the meters, collect rent, and troubleshoot the microwave. Even though I know he’s the dearest soul, still, I am a bit nervous. This will be our first interaction without a translator present.

True to form, even though I am prepared for his visit and have had a stack of American dollars flattening and smoothing for days, readying them for proper payment, I dither from the moment he buzzes the apartment. Because I don’t have a steady flow of people stopping by, needing to be let in, I haven’t used the security system much.

Hearing the buzz, I push the button that shows me the building’s exterior view. Yup. Someone or something is standing there, a blurry landlordish blob. Simultaneously, I lift the handset and warble “Allio?”

A tough monotone replies: “Slava.”

“Okay,” I half shout and hang up the receiver.

Flustered, I hit the security camera button again, realize it’s the wrong one, and then randomly punch three other buttons on the camera pad. None of them yields the tweeting sound that indicates I’ve unlocked the building’s front door.

Fuck.

I always know I’m an idiot, but I hate it when other people know it, too.

A few seconds later, the handset rings.

Again, I hear the terse “Slava,” but this time I lapse into a garbled English explanation that sounds something like “Sorry, I pushed the wrong button I don’t really know people here so I haven’t really done this before nobody ever needs buzzing in at my home in America we don’t have an intercom system I’m kind of a book reader more than a button pusher hahaha bad joke actually not a joke at all if you really think about it…”

On the other end, there is silence.

I push the correct button and hear the tweeting of the main building door unlocking.

Getting to the fourth floor takes Slava a couple minutes, time during which I hover uncomfortably inside the apartment’s open door, wanting to appear welcoming while, at the same time, worrying — because I have a faint recollection of some Belarusian belief that it’s bad luck to exchange money in a doorway, or maybe it’s just bad luck to give someone a bouquet with an odd number of flowers, or maybe it’s both, but mostly I am well aware I need to hand over a stack of money, and I still don’t pronounce “Zdravstvuyte” correctly. Will Slava think I’m sneezing if I try to greet him in Russian, and should I maybe have gotten him a dozen ‘mums to lubricate the rent payment?

***

In short order, I’ve handed Slava the rent, and he’s taken photos of the meters in the foyer and the bathroom. The bathmat next to the tub is askew, and I wouldn’t be surprised if there are a couple belly hairs in its folds.

When he enters the kitchen and opens the cupboard that houses yet another meter, his eyebrows jump.

Crap. Did I use a kabillion kajigawatts during the month of September or something?

“Is there a problem?” I venture, hoping “problem” is a word Slava will understand.

“Nyet,” he tells me, adding something that sounds like “Tak mnogo produktov.” I understand that last word: products. Dude can’t believe the size of my food stash.

Dude has no idea there’re three times as many products hiding in other cupboards, that he’s only glimpsing the tip of my issues. Dude has no idea he’s just clapped eyes on my “I’m going to a place called Belarus without my family” nerves made manifest, laid eyes on the comfort foods I brought from the U.S., witnessed the remnants of months of nervous preparation that resulted in a Mountain of Anxiety on our dining room table in Duluth: if I had a bad day in a foreign country, could the key to restoring mental balance possibly, perhaps, be a container of curried cashews from the Whole Foods Co-op? SHOULD I MAYBE PACK SOME TRADER JOE’S CANDIED PECANS IN CASE I EVER FEEL LIKE CRYING?

Slava recovers quickly from the surprise of my beef jerky hoard, snaps a photo of the meter, and turns his attention towards diagnosing the microwave.

First, he takes a pink, flowery plate out of the dish cupboard and sets it inside the microwave. Then, looking around for something to “warm,” he lands on a piece of scrap paper. Since I’ve explained to him through the translation app that the microwave works fine for four or five minutes, he sets the plate with the piece of paper on it inside the oven, programs the timer for five minutes, and hits Start.

I wish I’d watched more closely which buttons he pushed, as I have yet to figure out how to set a timer on the microwave. Instead, I stick to using the one button I faintly understand. If I push it twice, it yields a reasonable about of heating time before, of course, the entire machine goes dead. When I try pushing other buttons, the whole effort spirals into a cold-food snafu faster than you can say “Moy kartofel syroy.”

As it takes me thirty seconds to realize, five minutes is an incredibly long time to stand in front of a microwave next someone without speaking. Silently, we watch the piece of paper spin. ‘Round. And. ‘Round. At first, I try to fill the time by typing “That’s a delicious dinner you’re making” and forcing my phone screen in front of his face, but after my first attempt at app humor, I realize it’s a lot of work for both of us to act like I’m amusing.

I last another half a minute before I break. The microwave’s problems are something I can live with; so long as I can warm leftovers to an edible temperature, I’m not bothered. Typing the words “The problem with the microwave is no big deal” into my phone, I once again jam my phone into his face.

Reading the screen, he looks more puzzled than when he met my Anxiety Food Stash.

Oooooooh, of course “no big deal” doesn’t translate correctly! I hadn’t been thinking of it as slang, but I probably just told him “The problem with the microwave is small process of distributing the cards to players in a card game.” Coming at it more straightforwardly, I type, “It is not a problem.”

Nodding with comprehension, he uses my phone to respond. “If it gets worse, tell me. I will get a different one.”

***

Ten minutes later, just as I’m about to put on one of those facial masks that makes me look like Jason in Halloween, I see something red on the kitchen counter. It’s Slava’s phone. Once he stopped the microwave at my behest and pulled out the slip of paper — making me feel how warm it was — he’d booked towards the door, quickly putting on his shoes before he and his wife wished me a good night.

Apparently, for all of us, it was a relief to be done.

But damn. Now he’d have to come back for his phone, thus providing me with another opportunity to push seven buttons on the security pad and still leave him standing outside.

Sighing, I realize I should let him know his phone is here, lest he tear apart his car seats, thinking it’s slipped out of his pocket. Taking a photo of his phone on the kitchen counter, I send it to him. A minute later, I think maybe I should tell him I won’t be home later, so I copy and paste some words from the translation app into another message.

Wow. Slava’s phone keeps dinging. He sure gets a lot of notifications.

There’s a beat. then another beat. Plus one more beat…before my brain catches up with my behaviors. Oooooooooooh. Slava’s phone is dinging every time I send him a message. Yeah, he sure does get a lot of notifications — from me.

A few minutes later, the phone begins ringing. I look at the screen. Can I answer it? Should I answer it? Somehow, it seems wrong to answer someone else’s phone, especially without being able to speak the language.

After a few more rings, the thing goes quiet. So. How long until Slava realizes where he left his phone and comes back?

Again, his phone starts ringing. Again, I don’t answer it. And then again: it rings. I cave: grabbing it, I jab randomly at the screen. Hell, 80% of the time, I can’t answer my own phone and hang up on the caller by mistake. In some sort of miracle, though, I manage to swipe the right direction and establish a connection on this foreign phone. “Allio?” I croak.

It’s Slava, and because he launches into a whole lot of words in Russian, and because I have no idea what he’s just said, I simply agree, “Okay.” For all I know, I’ve just made a date to shave his back. But “okay.”

Twenty minutes later, he’s back at the door to the building, and after I successfully buzz him in, I start down the stairs with his phone, hoping to save him a few flights of climb. Meeting in the middle, our eyes lock, and we smile knowingly at each other: so, yeah, hi again anyhow. Before we head opposite directions, I use all my words on him, from “spaciba” to “das vedanya”; in return, he musters a hard-won “goodbye.”

***

Back under Sad Angel, I sink into the couch and smooth the lotion-infused mask over my face, feeling the muscles relax completely as they absorb both anti-aging promises and the fact that they no longer have to host an overly perky smile meant to compensate for lack of language. Hoping some ginseng fairy dust will manage to make my face look less like an unmade bed, I tip my head back and close my eyes as I muse on the appeal of my landlord.

If my life is a book, and I’m currently writing the Belarus chapter, then Slava is everything I could ask for in a character. He’s cute, complex, charismatic, cuddly, quirky. If I were creating a “landlord,” I wouldn’t come up with material as good as what he’s given me — warming a piece of paper in a microwave, crawling around frustratedly on the bathroom floor, proudly describing the expensive living room ceiling mural.

It’s the job of supporting characters to amplify the protagonist’s humanity, offer hope, play a role in a turnaround, remind the audience why the journey of the main character is important, heighten conflicts, advance the plot, or develop themes.

In my time in Belarus, Slava is a perfect supporting character. He is one of the few people to enter the intimacy of my home here, to know “too much food” feels about right to me, to have seen the half-read People magazine by the toilet, to know I am inept with seemingly straightforward tasks like pushing buttons. He is one of the few here who crosses the boundary from public to private interaction. Whenever I leave my apartment in Polotsk, I am dressed, wearing make-up, braced with the trappings of full public persona for whatever comes. But as soon I get home, I am, blessedly, just me again, my real self free to wander the rooms with poor posture and a finger up her nose.

Back in the States, my family knows my truest self. They live with her.

Here, though, I am the only one who knows My In-the-house Self.

Except, of course, for Slava.

He’s seen her, too, and despite these insider’s glimpses, he still smiles when he sees her.

And that very specific connection, especially in the midst of an intense experience that is a constant swirl of wonder and exhaustion,

feels like home.

Leave a Reply