After her beloved grandmother’s death, the specifics of Jayne’s molestation, stifled for so long, pushed their way out. The resulting confluence of grief, shame, and bewilderment caused Jayne to shut down completely. She was unable to concentrate, unable to lead her team of three other Covenant Players, unable to serve as their mentor out on the road; she was an emotional mess.

When Jayne’s grandma died, she and her team were in Northern Minnesota, staying in a host home. Jayne headed to Canada for the funeral and then rejoined her Covenant Players team in North Dakota. The team of stand-up individuals then accompanied Jayne to a town where they had performed previously, a place where Jayne had formed a deep connection with a loving family, the Dotans. Knowing that she wasn’t okay, that she was non-functional, that she was falling further into a pit of raw devastation, Jayne needed time to recover, so she took shelter in their support.

Initially, Jayne moved in with family who was friends with the Dotans; she lived with them for six months. After that, she moved in with the Dotan family and remained there for years. During that time, she began deliberately working on her abuse history and its resultant issues. Once she began facing and talking about the abuse that had occurred in her childhood, the serious weight gain began for Jayne. Similar to the same way a toddler who makes a leap in language development might experience a regression in physical development, Jayne’s body reflected the pain that her brain was processing. During her years with the Dotans, as she liberated her memories, grieved for her grandmother, and gained significant weight, Jayne also started attending college and became involved in theater and performance.

Then, in September of 1996, just as Jayne was getting some traction in her life, her mum was diagnosed with cancer.

As her mother’s health declined, Jayne reverted to her grandmother’s motto for comfort: “Fuck the world; let’s get ice cream.” During her mum’s illness, Jayne’s sister did much of the care taking since she was geographically closer, but Jayne got there as much as she could; she would alternate a couple of weeks of attending college classes with driving to Canada to help with her mother for a few weeks. Back and forth between worlds, helping usher her mum toward her death, Jayne–an emotional eater fighting through the worst of stresses–gained even more weight.

From the time of her mum’s diagnosis–to her death a year later–and with a few years of grief beyond that– Jayne gained a hundred pounds.

A changed body shape doesn’t necessarily change the essence of the person. Somewhat astonishingly, it’s entirely possible to gain a hundred pounds, or to lose a hundred pounds, without a similar change occurring inside. Yes, there is always a mind/body connection; at the same time, there can be a profound mind/body disconnect.

For Jayne, the disconnect meant that she was still going river rafting, riding motorcycles, going to the bike rally in Sturgis, South Dakota.

Yet while she remained active, a full participant in life, her subconscious knew something was afoot. In the years following her mother’s death, Jayne didn’t weigh herself. She refused to get on the scales at the doctor’s office.

As it can, pursuit of education gave her life forward momentum and purpose. Jayne earned her Associate of Arts degree in 1997, an Associate of Science degree in Corrections in 1998, a Bachelor’s degree in Sociology in 2000, and her Master’s of Sociology in 2003. Her Master’s thesis was a case study of a woman who’d been traumatically abused by her husband, a woman who’d also been a victim of childhood sexual abuse. The interviews they did together were hard for Jayne; sometimes, the sheer brutality her subject’s experience and its intersections with her own history caused Jayne to vomit. Thus, in addition to working on her issues with a counselor, Jayne’s education served as a form of therapy.

Then, in February of 2006, her second father, Mr. Dotan, was diagnosed with Stage 4 colon cancer. Two months later, Jayne’s dad–that born salesman who could have convinced a tribe of nomads they needed a camel load of sand–died. He’d lived as diabetic in denial, having undergone a partial leg amputation and problems with his eyes before his body gave out. Rounding out this spring of stress was Mr. Dotan’s death the month after Jayne’s father passed away. Bam. Bam. BAM.

In the face of these losses, Jayne hit a new low.

And a new high. Her weight had hit its peak: 436 pounds.

So there Jayne was: in her early thirties, finished with graduate school, working at a Parenting Resource Center, having lost both a surrogate and biological parents, feeling emotionally wiped out, weighing 436 pounds. Something had to give.

Fortunately, the same way education can change everything, so can a baby.

In this case, the baby was Jayne’s niece. This little girl, born the year before Jayne’s father(s) died, brought a new dimension to Jayne’s choices. She wanted to be there for her niece; as the last person alive holding the family surname, Jayne wanted to represent in this child’s life. Deep inside, she knew one thing: if she didn’t do something about her weight, she was going to die.

After several thwarted attempts, Jayne found an insurance company that looked at her BMI of 64 and agreed “Hell, YES,” a gastric bypass surgery was merited. In August of 2006, Jayne underwent an old-school, textbook “open roux en y” surgery. In the weeks after the surgery, she could have three one-ounce cups of liquid each day for her meals. After some time, she moved on to eating little squares of toast. If Jayne overate, she would throw up and become, as she puts it, “a hot frickin’ mess.”

Obviously, the change wrought by the surgery was huge, akin to applying defibrillator paddles to a heart in crisis. With her weight loss jump-started by the surgery, she lost 100 pounds in three months.

Whereas earlier in her life, Jayne had gained weight while letting out the secrets of sexual abuse, now weight loss opened up a channel that allowed other hidden information a means to come out.

Three months after the gastric bypass, Jayne was visiting her friend Sarah’s house, panicking because the initial weight loss was slowing down. Knowing that she’d failed at every other weight loss effort in her life, Jayne was gripped with fear, doubting that the results from the bypass would continue. Watching Jayne’s agitation, Sarah asked, “So what haven’t you worked on? If you’re an emotional person, and these feelings are connected to weight, what else is hanging out there? What haven’t you connected?”

Sitting at Sarah’s feet, Jayne finally allowed the dreaded words passed her lips: “I am gay.”

Immediately, she tried to suck them back into her mouth, to unsay them, even though Sarah’s reaction was no more threatening than a neutral “Are you sure?”

After that moment of coming out, Jayne sobbed for three days, drawing, writing, covering her bedroom floor in Sarah’s house with paper. Attempting to lend balance to Jayne’s emotions, Sarah challenged her to have a plan before she left and advised her, “Don’t jump completely into the gay thing.” Thus, Jayne went home and started talking to people. In short order, the music teacher at the college in town recommended a local woman named Claire as a resource to talk to. Claire, a lesbian, had been a college instructor until her retirement and had worked for decades as an advocate for sexual minorities.

One week after being given Claire’s name, Jayne ran into Claire at a play, in the lobby. Jayne used the moment to tell Claire–to ask Claire, “I’ve been told you might be able to talk to me.”

Looking closely at Jayne, Claire asked, “Is this the kind of conversation we can have at the coffee house, or do we need to meet at my house?”

They met at her house. They talked for hours. Claire proved to be the perfect resource for Jayne–affirming, questioning, explaining.

Bolstered by her talks with Claire, Jayne came out to her sister that Christmas. She came out to more and more people. Eventually, her friends were ready for her to hook up with someone, and when one of them asked, “So, Jayne, what are you looking for in a woman?”, the answer was, “Well, a 45-year-old version of Claire would do it for me.” Remarkably, the friend’s conclusion was not that they needed to search out such a person but, rather, that Jayne saw what she wanted in Claire. The friend urged Jayne to “go for it.”

And so it began.

Over the next few months of meeting with Claire, Jayne knew she was falling in love. When they would part from each other, the looming question was: “When I am going to see you next?” Their email conversations gained momentum. They became flirtatious. What Jayne realized, with each passing day, was that she was attracted to Claire emotionally, but not necessarily physically. In fact, she was on the verge of telling Claire, “I just can’t do this,” when, one night, Claire took her from a wine tasting to an evening at the theater, and then, during the performance, Claire reached over and grabbed Jayne’s finger and held onto it.

Jayne’s brain shut down as she asked herself, “Holy shit, what is this about?” That night, Claire kissed her on the cheek and all the next day, Jayne couldn’t stop thinking about Claire and “those fucking fingers.” From then on, when they were together, they sat knee to knee, teeming with schoolgirl crush. There was a lot more kissing. There was delightful groping. Unquestionably, the element of physical attraction had kicked in. As Jayne explains it, “When that switch flipped, from then on, when we lock eyes, I don’t see her age.” The way Claire frames their physical relationship is equally poignant: “I was her first, and she is my last.”

In the summer of 2008, friends and family from near and far gathered to witness their union. During the wedding ceremony, a very special guest–her willingness to attend this wedding stunned everyone–rose, walked to the front of the church, and gave a reading. Proving that the ghosts of the past can find peace, and that people are always more than we think, Jayne’s “Icky” grandma, the very proper British war bride, had found it within herself to attend her overweight grand-daughter’s lesbian wedding.

As Claire and Jayne were dating and committing, Jayne continued to lose weight, eventually getting down to 230 pounds. With a two-hundred pound weight loss behind her, she was wrapping and binding her torso every day due to excess skin. To truly be free of the weight and reclaim her body as a place she was glad to inhabit, Jayne needed to get rid of the bindings, so she had skin-removal surgery on her stomach surgery in 2009. This surgery took off a remarkable 19 pounds of skin from her belly and left her with 172 staples around her entire body. Also during this process, the surgeon lifted her rear end and created new belly button for her. Instantly, post-surgery, weighing in around 219 pounds, Jayne felt better, in terms of her self-perception. Finally–FINALLY–she was able to wear clothes that made sense, which resulted in a significant confidence boost.

It’s important to note that, as she was working on herself, Jayne was also helping others. Her primary job had her working with “at risk” students. In truth, every job she has taken has been quite deliberately chosen because it allows her to make a difference for others. She is exceedingly aware that “Key people saved me, made the difference, fostered resiliency.” As a result, Jayne’s professional life is devoted to giving it back–particularly in her work at the local high school, where she serves as a touchstone for the school’s “problem” kids. In addition to working to keep them on track, she also teaches at the community college and takes groups of teens to Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area on trips every summer.

Then, in 2010, Claire was diagnosed with cancer–a return of cancer she’d fought off twice before. The stress of that time, with driving back and forth to appointments, with her partner undergoing chemotherapy, triggered Jayne’s emotional eating habits. By autumn of 2011, Jayne was back up to 256 pounds, back in her size 16 pants. She realized she was losing control.

It was around this time that Jayne’s sister, who had become involved in selling and promoting the nutrition-and-wellness products of the company called Visalus, drafted Jayne as a distributor. If Jayne joined her sister’s team, she not only could help her sister, she also could help herself.

Visalus is a goal-oriented company, and Jayne is a goal-oriented gal. Because Visalus asks customers to state their goals publicly and then uses group support to help motivate participants, it was a good fit for Jayne (“You give me a challenge, and I’ll take it.”). Responding to Visalus’ challenges, Jayne went beyond thinking solely about diet and began incorporating exercise into her days–for the first time since childhood.

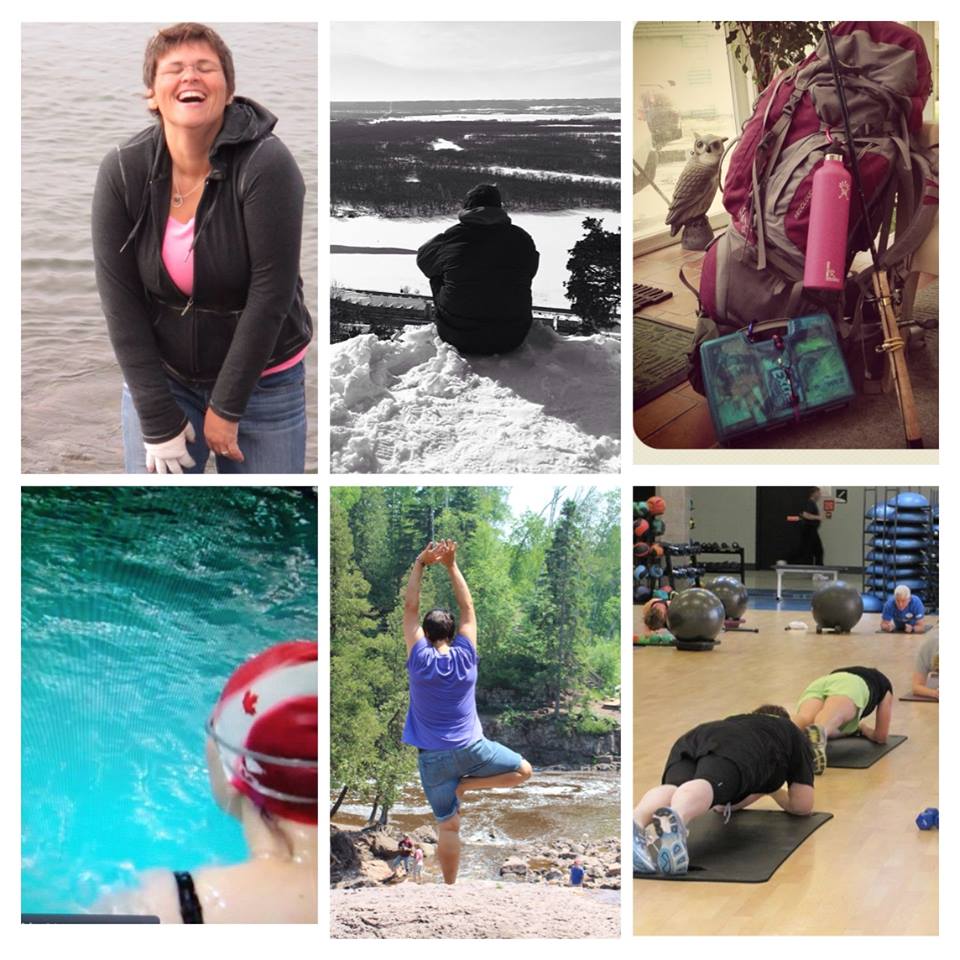

Throughout the course of several 90-day Challenges, Jayne fought back against the encroaching weight. To increase the challenge, she launched herself into a full-on madcap attempt to try out as many kinds of activities as she could manage. She bought a treadmill and ran her first 5K. She took a swimming lesson; with the technique of the strokes re-awakened, she began swimming regularly. She started attending yoga. She tried dog sledding, skjoring (being pulled on skis by a horse), downhill and cross-country skiing. She attended a Core Challenge class…which raised the half-joking question, what in her life so far hadn’t challenged her core?

With the exercise switch flipped, Jayne worked off the pounds. Even beyond Visalus challenges, her personal goal was to get to a point where she was satisfied with her weight and felt like she was “done.” At that point, she planned to reward herself with one last surgery: getting her “batwings”–the excess skin on her arms–removed. Without that surgery, her exterior would never truly reflect all the work she’d done, both in therapy and in tennis shoes. As she mulled over the idea of a magic number with regards to weight, trying to figure out when she could call an end to the fight, it became clear that there is no magic number and that weight, so plagued by emotions, is actually best when measured emotionally. Jayne had to ask herself, “Do I feel confident? Do I feel healthy? Do I feel like I can sustain this?” When she realized her answers to these questions were “Yes,” and when I doctor mentioned that, in his opinion, her body was at a good stage for the surgery, Jayne realized it was time to reward herself and get rid of the batwings. She was in the best shape of her life, swimming eight miles a week. She was ready to see what her swimming arms really looked like under all that skin.

In April of 2013, Jayne had the surgery on her arms. Going into it, she was terrified because it meant she couldn’t work out for six weeks, and her relationship with activity and a reasonable weight still felt new enough that she didn’t fully trust that it would always be a part of her life. During the recovery from the surgery, Jayne did gain fifteen pounds, but once she was given the go-ahead to move her body, she worked “like a mother-fu**er” to get it off. Her strongest motivation post-surgery came from the state of Minnesota, which had finally legalized same-sex unions. If she and Claire were going to get married “for real,” then Jayne wanted to look better than she ever had before. As their August wedding date approached, Jayne lost those fifteen pounds, and then some.

The wedding was the high point of a very high summer. At long last, her body felt truly healthy, and when she looked in the mirror, the person Jayne saw felt like someone she wanted to see. Fantastically, she could weigh herself at any point in any day, and the number on the scale was under 200 pounds. It felt suspiciously like Jayne had made friends with her body.

What’s more, with the fitness piece in place, and her arms actually looking as strong as they were, Jayne started to discover a long-hidden “girlie” part of herself. She went shopping. She bought dresses. She wore tank tops. She experienced the kind of moment that is folded away in the heart, like an unexpected love note, when she was attending a conference in Atlanta and had been having a terrible week. At a conference event, Jayne was wearing maxi-dress, and a beautiful woman came up to her just to say, “I’ve been noticing you, and I want you to know I really like the way you dress.” This compliment was incredibly well timed–the capstone to Jayne’s celebration of her new self–because a couple of days later, when she got off the airplane back in Minnesota, Jayne had to face a problem that had been bothering her. Strangely, her right hand had been and continued to be huge, seemingly infected.

After spending a day at Urgent Care, Jayne came home with a course of antibiotics. They didn’t help. Her hand continued to look like she weighed 436 pounds again. Something else was going on. Jayne met with a specialist at the Mayo Clinic, a woman whose empathy and understanding were exactly what Jayne needed. During their first appointment together, the doctor had a moment of revelation when Jayne lifted her arm and exposed, under her skin, “a cord.” Apparently, during her arm surgery, the surgeon had cut through a bundle of lymph nodes, which then created some cording. With this revelation came an eventual diagnosis. Jayne had lymph edema. The honeymoon was over.

Many people have seen women with lymph edema, women who are survivors of breast cancer. As a consequence of their illness and its ensuing interventions, they can end up living the rest of their lives wearing compression sleeves that compensate for what the lymph system is no longer doing: draining fluids. When we see such women, the response is sympathy, respect, gladness that they are still alive.

For Jayne, cancer wasn’t the culprit. The fact that she’d undergone an elective surgery–“I was vain”–and ended up with a lifelong side effect ate at her. For the first twenty-two days after her diagnosis, Jayne cried every day. Her emotions swirled from regret to anger to outrage to guilt. The guilt came only partially from her feelings that she’d been vain; the bigger cause of her guilt was the face that Claire’s cancer, held for months in a kind of remission, had returned. They had learned on September 4th that the tumor in Claire’s pelvis had doubled in size during the previous three months. She would be returning to chemotherapy. Then, in early October, Jayne got the diagnosis of lymph edema, subsequently feeling herself crash from the highest of the highs to the lowest of the lows.

Between the two of them, they were sometimes attending seven appointments a week at the Mayo Clinic. When one works more than full-time and is constantly driving 45 minutes to the hospital, it’s hard to find time to go have a restorative swim at the pool.

Jayne was going to physical therapy, getting medical massages to help drain the fluid out of her arm, learning that she can anticipate being on antibiotics frequently for the rest of her life, as a scratch or a cut will likely result in infection. At the same time, she was being loaded up with information about how to wrap her hand (all day, every day), how to deal with the cracks in her skin that result from daily wrapping, how she will have to monitor her physical activity so that she just barely hits her limit and stops before she overdoes it; she was learning that there was no such thing any more as waking up and dashing out the door. Her hand, for the rest of her life, will require constant, detailed, careful, time-consuming tending.

With so many appointments and so much emotional fallout, Claire and Jayne were struggling. One of them had cancer; one of them had lymph edema. The stakes were radically different for each of them, yet Claire’s insidious tumor was a quiet thing that needed periodic tending while Jayne’s hand was a big, visible thing that requires constant thought and care. Jayne’s mind was consumed with her sadness over her hand–over never again wearing a maxi dress without its impact being marred by the presence of a fistful of gauze and a compression glove–yet it’s not as though she was dying. For months, she struggled with the anguish of letting herself feel her own pain while trying to acknowledge that it was something she could live with. Going into the closet to put on a dress resulted in a good cry rather than a personal celebration.

Fortunately, the escalating tensions in their household were defused by the promise of travel. Both Claire and Jayne love to travel and have had some of their very best times as a couple after getting on an airplane and winging off to sights unseen. Now, it was time for their honeymoon, even though it felt like the honeymoon had ended in the Mayo Clinic.

Although both women were well traveled, neither had been to South America before. To celebrate their legal wedding, they had planned a trip to Peru and Machu Picchu. The time they had together was a perfect balm to what ailed them. Claire cuddled a baby sloth. It peed on her; she never wanted to wash that shirt again. In a native village, Jayne shot a blow dart. They went fishing for piranha. Claire, months later, still carries the jaw of a piranha, well protected in a Ziploc baggie, around with her.

Thus, their honeymoon trip restored something important between them. It also presented Jayne with the chance to take her hand on the road and learn to deal with it outside of normal daily existence. Plane travel is terrible for lymph edema, and so Jayne’s hand was a mess. Yet she had a great trip.

If a messy hand and good times could co-exist, then maybe everything was going to be all right.

Initially, as she grappled with the development of the lymph edema, Jayne kept uncharacteristically quiet about it. An extrovert who needs to externalize to process, she made no public announcement of her new condition. When she was out in the world, she would pull down her sleeve and try to cover her bandages. Outside of a close circle of friends, she didn’t tell people. Those who loved her would want to be outraged on her behalf, to yell that she should sue the surgeon, to overlook the fact that lymph edema is listed as a potential complication of the arm surgery, to forget that Jayne signed off on the idea of potential complications. Before she could handle people’s reactions to the edema, she needed to be more in control of her own.

And then, after a few months of struggling with the intersection of her and Claire’s diagnoses; after learning to deal with the minutiae of her hand; after taking a wonderful trip with her love; after considering that she might, in fact, consult a lawyer; after feeling herself completely crumple; after making herself get back in the pool regularly;

and after standing back up and shaking her swollen fist to the sky–

Jayne came out–

this time with a disclosure of the lymph edema. She told everyone: her friends, her family, her co-workers, her students.

When the flood of their reactions hit, Jayne wasn’t swamped by them. She didn’t drown in their loving outrage and concern.

Nope.

She handled them. She helped her friends, family, co-workers, students feel better about her condition. She was ready.

And as she swam through the wave of love, she stayed afloat.

She became the hero of her story.

Leave a Reply