He was such a nice guy, one of the first to make us feel comfortable when we moved to the village in central Turkey. Thus, it was a shock when he asked me to become his mistress.

Because his store was on the main drag, on a corner our family passed whenever we walked home, we had a habit of exchanging daily hellos. “Merhaba, Murat!” I’d cry as we trudged to our house from the bus stop, backpacks and bags full of groceries from the neighboring town.

While our relationship was based on the superficial–what with us not knowing any Turkish verbs, much less words for abstract concepts–Murat could be counted on for a smile and a hearty greeting in return. Standing outside his liquor store, his head bent as he lit a cigarette, he’d spy us out of the corner of his eye and beam. Casting a wave our direction, he’d call out the phrase he’d taught us during our first week in Cappadocia: “Nasilsiniz?”

How were we? Well, we’d just bought chicken and peppers and chocolate bars. We were good. Waving back, I’d assure him, “Iyiyim. Çok iyiyim!” Then Byron would join in, asking the assemblage of men–Murat’s posse–“Siz nasilsiniz?”

They, too, were always well. We were always “good.” They were always “good.” Given our limited Turkish, we didn’t know how to be anything else with each other. Even if Paco had been complaining about the heat, and the reek from the bus driver’s armpits had made Byron nauseous, and we’d have gladly swapped 10,000 peppers for just one head of cauliflower, and I’d had both kids perched on my sweaty knees during the ride back to the village because of the crowding, we had to be “good!”

Often, we’d stop at Murat’s shop to stock up on beer and wine. It was from him that I learned the words beyaz and kirmizi (“white” and “red”). Often, he’d grab a bag of roasted chickpeas off the rack and toss it to the kids, announcing, in English, “my gift.”

In return, the kids’ gift, because somebody fetched them up right, was their ability to put a few of those roasted chickpeas into their mouths, chew for a minute, and look pleasant–instead of spitting them out with a loud “PATOOOUUUI. These crappy things taste like chalk! What are the Turkish words for ‘Please swab my mouth with lemon cologne’?”

One thing my children unquestionably learned from that year of travel is this: if you don’t speak the language, plaster a smile on your face and act appreciative, even if you suspect you’re being poisoned.

That’s what happens when one doesn’t have command of the vernacular. One suffers poisoning without protest. One is diminished–flatter, without the dimension created by verbs and abstract concepts. No matter the turmoil roiling inside, one must always be fine. Intelligence and humor burble up, looking for expression; lacking conveyance, they remain bottled. Not being able to share one’s thoughts, one’s nuances, is lonely, deflating, crazy-making.

Unable to communicate fully, a person feels powerless.

Fortunately, there are ways to connect that go beyond the words stored in our heads. For example, there are gestures and the prodigious, forceful effectiveness of body language. Our neighbors in the village–the komsu–managed to transmit their ability to be pushy, annoying, nosy, kind, generous, greedy, thoughtful, and desperate, all through the six overlapping words we shared with them.

Also, there is the invaluable translation tool called “I made a friend who speaks the language, and I will cement my hip to hers and have her talk for me.” Indeed, such people are aspirational, the BMWs of pals in a foreign country: we treasure them and park them in temperature-controlled garages in return for the pleasure of basking in their shiny linguistic prowess. We had several such friends during our time in Turkey, men and women who helped us find a place to live, who negotiated our “lease,” who called the cable company, who cursed out overcharging taxi drivers, who asked my questions about headscarves, who put voice to the thoughts stalled in our heads.

Not only did they lubricate social and transactional situations for us, they were our best teachers, able to explain appropriateness, pronunciation, and the mores surrounding certain usages. Because she is fluent in both English and Turkish, our friend Ileyn was able to explain why her daughter addressed me as “Abla Jocelyn” (sister) and not “Teyze Jocelyn” (aunt). Because she’d figured out how to maneuver through the practicalities of Turkish life, our friend Christina taught us to call “Inecek var” to the mini-bus driver when we wanted him to pull over. Because he had lived in Turkey for more than thirty years, our friend Andus (and his wife Gulcan) was able to talk to people in uniform about why they wouldn’t stamp their seal on our some of our residency paperwork. Without the aid of friends who could straddle the languages, we would have left the country knowing ten words and not a hundred. It’s not often math can be applied to relationships, but they made our experience ten times easier. Carry the two.

Of course, in this modern age, we also have technology to help us, thanks to online software and translation sites. On a rote level, these sites are extremely helpful, for they contain dictionaries and phrases that respond to an off-the-cuff “Let me plug in these words in English and get a straightforward answer to my linguistic conundrum.”

Then again.

Just last week, Paco was writing a story in Spanish, and he was uncertain about the phrase “Once upon a time…” along with some of his verb choices. Relating the adventures of a monkey named Bob gets really complicated, really fast, when you’re doing it in another language. We were using online sources, but I didn’t trust their results, so I messaged my sister. She’s a Spanish/English bilingual teacher and has, previously, lived in Spanish-speaking countries, so her understanding of the language is authentic, responsive to specific contexts. As it turns out, the Internet had yielded the correct wording for “Once upon a time…” Supplementing cyberspace was big sister Allegra, who’d come in the room, looked over Paco’s story, and helped him make some edits (while also complimenting his range of verb tenses–“I didn’t learn the imperfect ’til this year, Paco! I can’t believe you already know it!”). By the time we started chatting, my sister really didn’t need to weigh in with much help. Thus, we veered off topic, chatting about random things, such as the fact that Allegra’s and my current happy jam, a song called “Shut Up and Dance” by a group named Walk the Moon, is also my sister’s current car jam. Quickly, I opened a tab for Google Translate and input “shut up and dance”–because I wanted to tell my sister, in Spanish, that she should do just that.

The computer told me: “cerrada y bailar conmigo.”

My sister told me: “nope.”

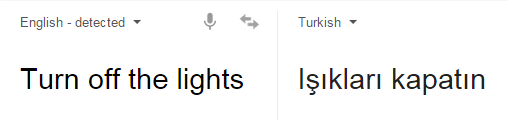

Then she explained that it should actually be cállate y baila conmigo because cerrada means closed or shut, like a door, not like “shut your mouth, you yappy thing.” This distinction brought to mind the difference between Turkish and English when it comes to something like making a room dark. In English, we “turn off” the lights. In Turkish, the lights are extinguished–a holdover from the age of torches and candles. Most online translation programs don’t catch that particularity or provide common usage.

Rather, the results of a simple online search are very literal:

With a bit more digging, however, the curious searcher discovers it’s a very different verb, in fact, that’s actually used to make the artificial overhead fluorescence cease with its oppressive intensity:

For me, whenever I start wriggling down the rabbit hole that is using translation software–typing, checking, cross-checking–I almost immediately crave the help of a fluent speaker, for clarification, explanation, and affirmation. I want a bunny familiar with all the twists to reach down and give me a good yank. As bunnies do.

I could’ve used a fluent speaker and a good yank one day in Murat’s shop. ‘Cause a big hole opened up right there next to the pomegranate lokum, and I nearly toppled panties first into it.

I know. Imagine the wedgie.

Friends, arkadaslar, amigos: Google Translate tried to bust up my marriage.

After many months of enjoying our daily wave and “How you doin’?” conversations with Murat, I had stopped in his shop with the kids–Byron was far down the dusty main street drinking the obligatory third cup of tea while attempting to mime the words “I would like to buy a hammer” to the guys at the hardware store–when I noticed an enlarged photo of a young man hanging on the wall. In recent weeks, Murat had overhauled his shop, changing it from a liquor store into a fruit-and-nut shop. We didn’t know why he’d made this change–until I pointed to the enlarged photo and attempted to ask “Who is that?” The boy in the photo, a teenager, was surrounded by clouds and beams of light; because most portraits I’d seen hanging in Turkish homes integrated equally cheesy backdrops, I didn’t think much of the boy’s heavenly surroundings.

But then Murat’s eyes filled with tears, and he explained, haltingly, in English, that this was his son. Had been his son. There had been an accident with a car and a motorcycle. His son, age 15, had died. Apparently, this had happened relatively recently. Trying to explain his heart’s pain in thirteen words, Murat swung his arm wide, indicating the baskets of dried apricots and sesame peanuts, and said, in English, “No more Boy. I…No beer. No wine. I good Muslim now. For Boy.” His face crumpled.

It was a terrible moment.

In response to his disclosure, my first response was physical; I wanted to step towards that crumpled face and envelop the bereft father in a hug. To merely stand there, attempting to emit sympathy from a distance, felt clinical, but in a Muslim culture, the separation between men and women runs strict and deep, even when the woman is a foreigner. And I certainly didn’t have the words, in Turkish, to throw across the divide as a bridge of comfort. Of course, sometimes it’s not the words but, rather, the presence of them, that reassures us we’re not alone.

I wasn’t sure Murat understood when I murmured: “I’m so sorry. What has happened to you is an unthinkable tragedy. The kind of grief and pain you are living with break me, on your behalf. The love you had for your son gave him a good life, I’m sure. But, oh. Murat. I’m so sorry.” However, it wasn’t understanding of vocabulary that he needed in that moment. It was my tone, the shine of tears in my eyes, the communication of compassion, the flow of another voice. He heard what I was saying. My murmur was the language of common humanity, the one that runs beneath words.

Slowly, dashing the back of his hand against his eyes, he nodded, accepting my condolences. Daring in the moment, I reached out and patted his shoulder. He smiled.

Straightening his shoulders, he grabbed a bag of chickpeas off the rack and handed them to the kids. Their grins of thanks were carefully pasted on. Trying to change the mood, Murat asked if there was anything I needed from his store.

Had I been able to, I would have said, “I’ll take it all. Fifty baskets of nuts. Thirty baskets of dried fruits. Everything on all the shelves. I’ll take it all, even those boxes of spice paste labeled Turkish Viagra“–just to give him a new story to tell.

Without a million lira in my wallet, though, I could only request, “Could I have 500 grams of pistachios?”

As Murat scooped the nuts into a bag, we went through our ritual of pointing at various items and pronouncing the Turkish words followed by their English counterparts. After a few minutes of laughter at the mangled sounds coming out of our mouths, Murat tried to form a question–“You. I…?”–before filling in the rest of his thought with words that were beyond my ken. He stopped. Thought. Tried again. I was baffled and told him, “I don’t understand.”

Tapping his finger to his forehead, he raised his eyebrows and pointed to the laptop set up near his ashtray. Sitting down, he opened a browser and typed in his question. The words popped up in English, and he turned the screen so I could read the translation:

Perhaps sometimes at night you could come be with me so we could be together.

Allah help me. Dude wanted to hook up.

That’ll teach me to write a multi-pronged sabbatical plan, get it approved by administration, spend months figuring out a way to live abroad, rent out our house, pack the family into a plane, fly twelve hours over the ocean, fall to pieces in 104 degree heat, rent a 400-year-old Greek house, start homeschooling the kids, take a crowded mini-bus to the neighboring village for peppers, and then pat a crying guy’s arm. That sympathetic arm pat had, apparently, announced open season on my panties.

And I don’t even like the word “panties.” I just use it to make myself cringe. Panties, panties, panties. PAN-TIES. If I knew the word for panties in Turkish, I’m sure it would make me shudder, too. Turkish panties, Turkish panties, Turkish panties. TUR-KISH PAN-TIES.

Wait, Google Translate just told me the Turkish word for panties is külot. My people: our culottes come from the Turkish word for panties, panties, panties!

Unless Google Translate is, as usual, all messed up, and the actual word natives use for their panties is nikur.

I should have asked Murat.

That would have gone wellopenseasononnikur.

Instead of raising the panty question with Murat, I wisely opted for a beat of silence as I digested his translated words. Perhaps sometimes at night you could come be with me so we could be together.

He was such a nice guy, without a whiff of creep contaminating his aura. He was always kind to my kids, happy to see my husband. His son had just died. He probably had a wife. He had recommitted to his religion. He had launched a store where tourist buses stopped each day, allotting passengers ten minutes to stock up on his authentic (otantik) goods. It would be helpful to the health of his business if he could speak more English. He knew I was an English teacher.

His proposition wasn’t a sex thing. His proposition was a language thing.

So I read the words on the screen, reeled, gulped, processed, re-centered, and agreed that it would be lovely to stop by on occasion and work on vocabulary: “Evet! Çok iyi.”

Pistachios and children in hand, I headed out the door, onto the main drag teeming with men drinking tea, donkeys braying, motorcycles roaring by, komsu angling to make a lira, gangs of kids kicking balls. As I turned to wave goodbye to Murat, the evening Call to Prayer began to echo throughout the village.

Pulling the door of his shop closed behind him, Murat lit a cigarette, waved in our direction, and began to walk towards the mosque.

He didn’t have to say a word.

I knew what he was about.

No translation necessary.

———————————

**Apologies for the fact that my Turkish spellings aren’t always strictly correct; WordPress is a bitch about using the Turkish alphabet on this English-based blog. Incidentally, Google Translate tells me the Turkish word for “bitch” is orospu. I dare you to try it out in Istanbul at the Blue Mosque.

Leave a Reply