I don’t have a favorite book.

I have multitudes of favorite books–linked to specific phases of my life, places I’ve been while reading them, reasons why they were just the right book at the right time. In truth, many of my favorite books aren’t remarkable, from a writerly standpoint, yet they are important to me, emotionally.

In my youth, and to this day, the Betsy-Tacy-Tib series by Maud Hart Lovelace has ruled my heart. Lovelace’s prose is not noteworthy, but I have read those books multiple times because I savor that journey back to the early 1900s, when pompadours were in vogue, and games at hen parties consisted of seeing who could remove the peel from an apple in the longest unbroken strip. Whenever I read these books, I grow up with Betsy once again and feel an ache in my heart as I hope Joe falls in love with her, me, us.

Then there are the works of Wallace Stegner–arguably the finest author the United States has produced; there is no questioning his ability both as storyteller and sentence stylist. Thinking of his books, I recall a profoundly lonely summer break during college when I lived in a mostly empty fraternity house in Evanston, Illinois, commuting to Deerfield for my job at Prentice-Hall publishing. All day at work, hacking away at my assigned project of updating the Rand-McNally travel guides, I would telephone hotels and resorts around the country, checking to see if they still accepted Visa and if their rates had gone up. I knew no one in the area, save a single friend with whom I worked, and would return to the frat each night, drop my bag on the linoleum floor tiles, recline on the prison-quality bunk beds, lean against the cinder block walls, and watch my most reliable companions, Roseanne and Murphy Brown, flicker on the black-and-white television’s 12-inch screen. Over dinners of thick egg noodles stirred with Ranch dressing squeezed out of the bottle, I cracked each of Stegner’s books and let his lyrical prose sweep me to the American West, a place where water is scarce, the wheelchair-bound research their pioneering grandparents, and violence in saloons can lead to love. At the end of the summer, I’d read Stegner’s entire oeuvre and considered him my savior.

A handful of years later, I found solace and adventure in Elizabeth Arthur’s Antarctic Navigation, a book about South Pole exploration that dovetails perfectly with my polar-literature mania. Normally, all I ask of such books is that an under-stocked ship become ice-locked for two years, the hull crushed by pressure, as morale and civility dwindle–bonus points awarded to books that detail cannibalism, poisoning the captain with arsenic, boiling shoes for dinner, and acting nonchalant as half of the surviving members of the expedition float away into the night when the ice upon which they were sleeping cracks off and becomes a floe. Interestingly, Antarctic Navigation covers none of these topics, yet still it sticks with me, most likely because the heroine is a passionate, obsessive type who attempts to re-create the doomed expedition of Robert Falcon Scott (After-the-fact advice, Scott: use dogs, not horses, but if you insist on using horses, don’t be surprised when a couple of ’em get taken down by killer whales. Duh.). It also sticks with me because I first read it when I was deeply committed to a relationship that was sucking away my self-esteem and hope for the future–yet I was still three years away from awareness of these attenuations. When I read the last few hundred pages in the book–the proverbial race to The Pole–I was sleeping in a separate bedroom, away from my boyfriend; he said he slept better with me in a different room. At the time, it all seemed very logical. Fortunately, being in a separate bedroom allowed me to turn page after page through the dim hours of the night. When finally I slapped the back cover closed, I looked up and was startled to see the morning sun trumpeting through the blinds. It was 7 a.m. The book had almost 800 pages. Always enamored with a feisty heroine, it took me 1000 more days to rediscover the one stooping inside me.

And so. There are stacks of influential books whose greatest appeal is the emotional support they’ve provided me. Yes, the writing is good, often excellent. Yes, there is much to be learned about the world from them. However, I love them because they were sustaining friends.

In contrast are books that dazzle me when I’m not reading from a place of neediness but, rather, from a place of I Just Want to Enjoy Some Good Writing. This is not to say that such books aren’t also sustaining friends; it’s more that, these days, I’m looking for books that make my knees weak with the glory of their cadence, structure, content, and storytelling. When I crack a cover and dive in, there is no greater delight than discovering a fresh, original voice in the pages–the kind of singular voice that makes me think, “If this book were translated, readers of the translated language would be missing out. It would be impossible for this book to read as beautifully in any other form.”

With many books, from the Betsy-Tacy-Tib series to Antarctic Navigation, I wouldn’t bemoan a translation. Put into German, Thai, or Turkish, these books would not lose their essential appeal. But: with books that have greatness in the writing, I worry, fretting, “If someone reads this in another language, it won’t be right any more. It won’t be the same.”

As is usually the case with worry, it’s wasted energy. The issue with translation isn’t that it happens but, instead, that it needs to be handled with a deft hand and a precise eye. I’ve been thinking about this lately as I consider some books that have just about blown my bifocals out. They are that good.

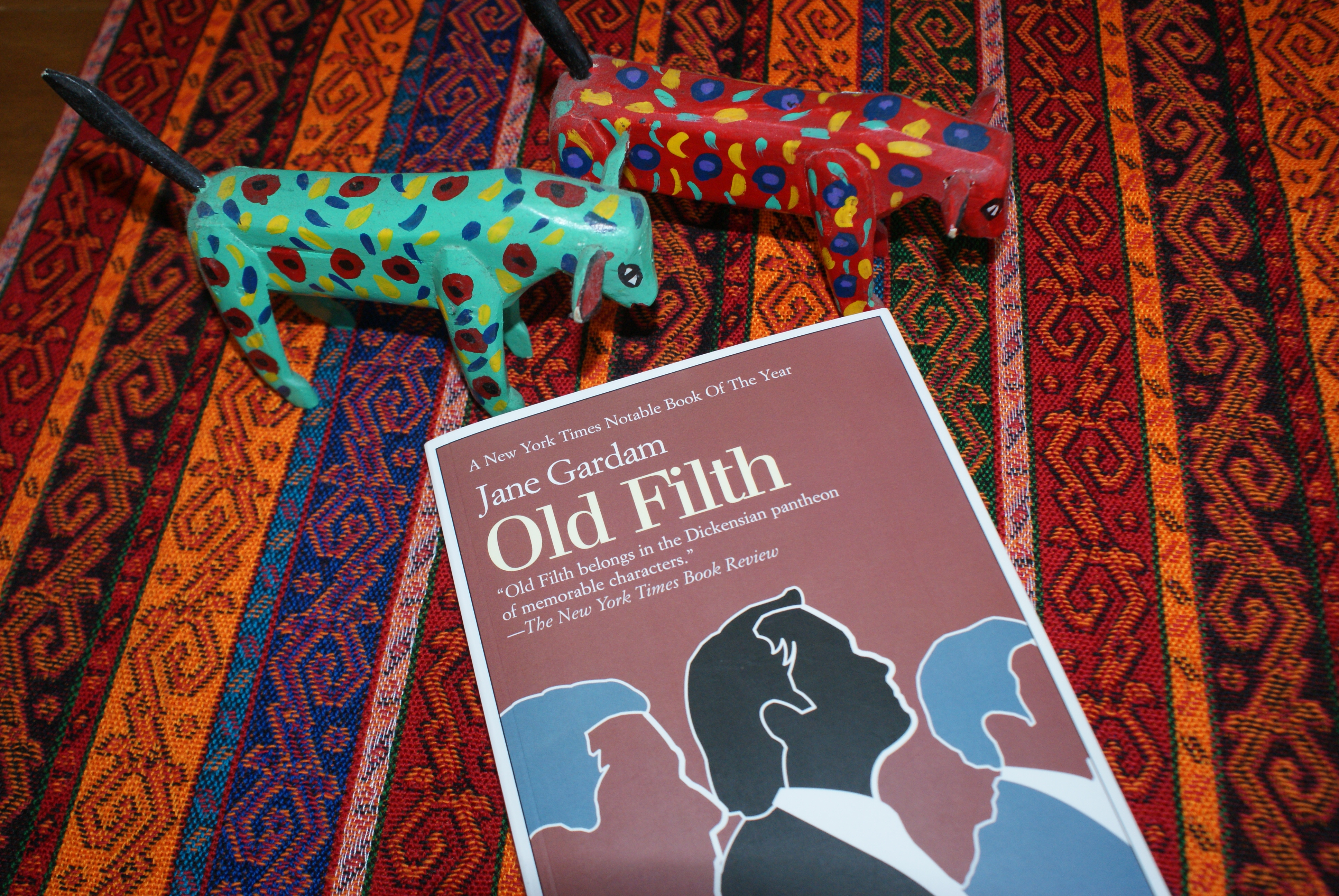

Indeed, in the past year, I’ve encountered two series that have impacted me deeply. While reading both Jane Gardam’s Old Filth trilogy and Elena Ferrante’s “Neapolitan Novels” (three so far, with the fourth and final installment being released in September), I went through the stages of Enchanted Readership: from excitement at having found books with strong voices to joy at being in the presence of intelligent, talented authors to wonder at what they were able to achieve on the page to sadness that the reading experience was finite. Nothing commends a book more highly than a bereft reader turning the last page–slowly and reluctantly. That’s how I was with these books.

Get this, though: Elena Ferrante writes in Italian. I was reading translations of her originals. Slap me to Sunday and dunk me in the lake if the process of translation diminished her work in any way–for her novels, which follow two tough girls growing up in a poor Naples neighborhood as friends, competitors, touchstones, nemeses, are powerhouses. Ferrante is writing more than “girl friendship” books. Integral to these books are the neighborhood, the political times, the realities of the economy, the ingrained class system. They are intricate and detailed, and if you’re someone who often sighs deeply at how long my blog posts are, please don’t go near these books, as they are not the stuff of short paragraphs and easy take-away. These books require readers to show up and invest. The pay-offs are immense. After finishing each one, I was left musing, “Elena Ferrante is more than a feminist or an author who’s not interested in pandering to an audience. She’s a badass.”

And that’s what astounds me most: I read her novels in translation, yet Ferrante’s essence has not been lost–even when one is reading her Italian stories in English, it is clear that this author is uncompromising and tells her stories exactly the way she wants to tell her stories, the way she needs to tell her stories. Minna Proctor, a reviewer at Bookforum, handily summarizes Ferrante’s achievements: “Ferrante’s writing is so unencumbered, so natural, and yet so lovely, brazen, and flush. The constancy of detail and the pacing that zips and skips then slows to a real-time crawl have an almost psychic effect, bringing you deeply into synchronicity with the discomforts and urgency of the characters’ emotions. Ferrante is unlike other writers—not because she’s innovative, but rather because she’s unselfconscious [sic] and brutally, diligently honest.”

While I am blown away by Ferrante, I’m also blown away by Ferrante’s translator, Ann Goldstein. To keep a writer’s tone, fierceness, and intentions intact while changing all the words…that’s a phenomenal talent in itself. An excellent human translator is to rote online translation programs what 70% cocoa dark chocolate is to a Hershey’s bar.

The success of translation with Ferrante’s novels makes me hopeful that an effective translation of my other recent favorites, Jane Gardam’s Old Filth trilogy, might also be possible.

However, my gut says it would be impossible for such distinctively British books to work in any language except English. So much would be lost in translation–for example, the fact that “Filth” is an acronym for “Failed in London Try Hong Kong” means a translated version would have to take on an entirely new title. So much would be confusing to readers in various places around the world–for example, readers would need a well-established knowledge of Great Britain’s history with colonialization and attempts to bring “civilization” to countries in The East. When I think of moving these books out of their original language, I despair on Gardam’s behalf.

If an eighteen-year-old boy in, hmmm, Tanzania got his hands on a copy of Old Filth that had been translated into Swahili, he would struggle with this sentence about the book’s protagonist, Old Filth, and his wife: “But if any old pair had been born to become retired ex-pats in Hong Kong, members of the Cricket Club, the Jockey Club, stalwarts of the English Lending Library, props of St. Andrew’s Church and St. John’s Cathedral, they were Filth and Betty.”

Actually, before that sentence ever landed in the Tanzanian boy’s hands, how would a translator have handled putting concepts like being “ex-pats” and “props” into Swahili? Could a single word in Swahili match the English? If not, would the translator need to use long phrases to convey the concepts? If so, wouldn’t Gardam’s prose have been fundamentally altered by the process of translation?

On the other hand, if a book is magnificent, should concerns over translation keep it out of the hands of a reading public, no matter where they are in the world and what language they speak? If I think Old Filth is a great book, shouldn’t I want everyone to read it? Even if a Tanzanian boy knows nothing about British culture and is confused by much of what he reads in something like Old Filth, what better way is there for him to become acquainted with clubs and lending libraries and cathedrals? Where else in his life might he encounter insights into barristers, judges, advocates, and “The Court”? If not for reading about it, would this Tanzanian boy ever know that British parents stationed in The East often sent their children home to England for their schooling, creating an entire group of children known as “Raj orphans”?

Thus, although the protective reader in me wants to yell “Don’t even bother to translate these fantastic books, for too much will be lost!” as she clutches treasured volumes to her indignantly heaving bosom, the truth is she, that wild-eyed nut, should be locked into The Conservatory with Colonel Mustard and a lead pipe to see who comes out alive.

Of course sublime books should be translated. Even if nuance is sacrificed in the process, even if the original beauty of the prose gets corrupted, the gifts innate in every book should be available to all readers, no matter their language.

I learned about pompadours from Maud Hart Lovelace.

I learned about fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva from Wallace Stegner’s Angle of Repose.

I learned, from Elizabeth Arthur, that the National Science Foundation awards some grants to writers and artists, in an effort to open the experience of The South Pole to more than scientists.

I learned about Italy’s Red Brigades from Elena Ferrante.

And, like that apocryphal Tanzanian boy, I learned from Jane Gardam about a group of children known as “Raj orphans.”

Ultimately, with books, perhaps it’s not actually about the words. Perhaps the greatest gift they offer is that of exposure–to culture, to history, to ideas, to human nature.

They bring us the world.

All 6,500 languages of it.

Leave a Reply