During sophomore year of high school, my English teacher was named Mrs. Rice.

We can’t accuse Mrs. Rice of being overly fond of the redhead in the second row.

As I review the work I did in her class, it is apparent that Mrs. Rice was a seasoned teacher. I wasn’t the first “Look at me, I’m cute — except I’m mostly an idiot” student to gallivant into her classroom, giggling and checking the crispness of her hairspray.

Mrs. Rice was not impressed.

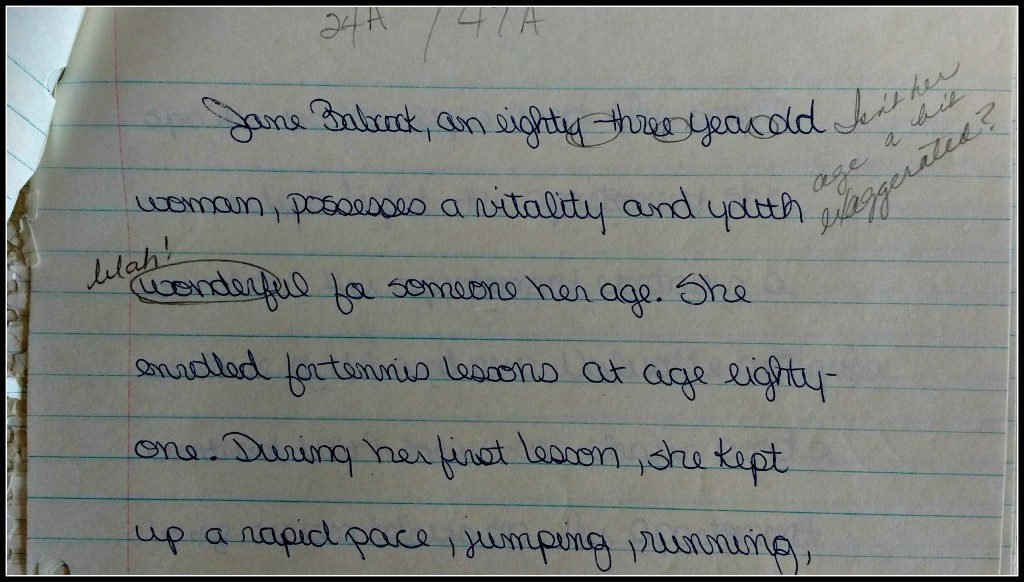

Exhibit A:

In the first sentence of my “character sketch,” Mrs. Rice called me out twice, first asking “Isn’t her age a bit exaggerated?” before commenting “blah!” on my use of the word wonderful.

While I concede my opening sentence is not wonderful tight, I’d also argue it’s a reasonably solid sentence from a fifteen-year-old. But nothing escaped the correction of Mrs. Rice’s pencil.

Even now, as I type this, I can hear her bones rolling around inside her coffin as her skeletal hand scrambles to find the grading pencil she was buried with — so that she can scrawl “Do not open sentences with coordinating conjunctions” all over my blog posts. Then again, maybe Mrs. Rice is still alive; I don’t know what became of her after I tripped my way out the door at the end of her rigorous class. Probably, she breathed a sigh of relief so extended that her next inhale didn’t occur until 1984.

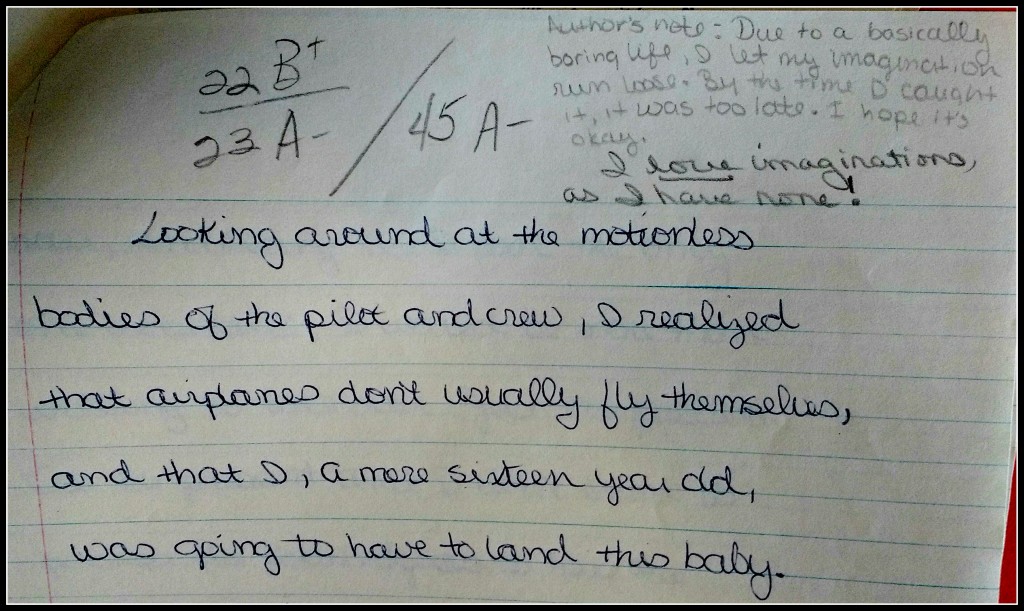

What tickles me most about Mrs. Rice and her comments is that now, 33 years later, I am Mrs. Rice. Like her, I am witness to the half-efforts of distracted students, often dragged down by the dreck, perking up when work that is original and thoughtful crosses my vision. Too often, I suspect, my comments err on the side of sharpness rather than understanding. Thus, the review of my early essays is proving a helpful teaching tool. As I look at what I wrote when I was the student, I remember that I was truly trying. I wanted to be clever, articulate, admired. I wanted to express intelligence in my writing, and as I pushed into her assignments, I believed I was digging deep.

Three days after I submitted a masterpiece, the graded copy, shriveled and apologetic, would land on the desk in front of me. Leafing through the pages, I’d read the incisive, poison-dart comments shot into my prose, and I’d feel like a dolt.

At the same time, once the sting faded, I learned from her critique.

For me as a teacher, I need to remain aware of the power of my feedback. Because writing comments is such workaday stuff, I too often forget that there are real people crouching behind the writing — real, quivering people with feelings. Ideally, I’ll forge a Grading Spirit Animal that draws from the best of Mrs. Rice while folding in a bit of Michelle Obama and Mr. Rogers. Fortunately, all of these inspirations have demonstrated a fondness for cardigans, so that’ll be my go-to look whenever a heap of papers hits my Inbox.

Look at me, digressing. That last paragraph, winging off in a whole new direction simply because I wanted to express those thoughts, would’ve caused the tip of Mrs. Rice’s pencil to snap.

Refocusing, then, on the summary message sent by Mrs. Rice’s comments: I annoyed her. More likely, I wasn’t much on her radar at all, and if I were, she thought I had promise but was choosing not to fulfill it.

I’ll grant her that hypothesis.

Her annoyance was legitimate.

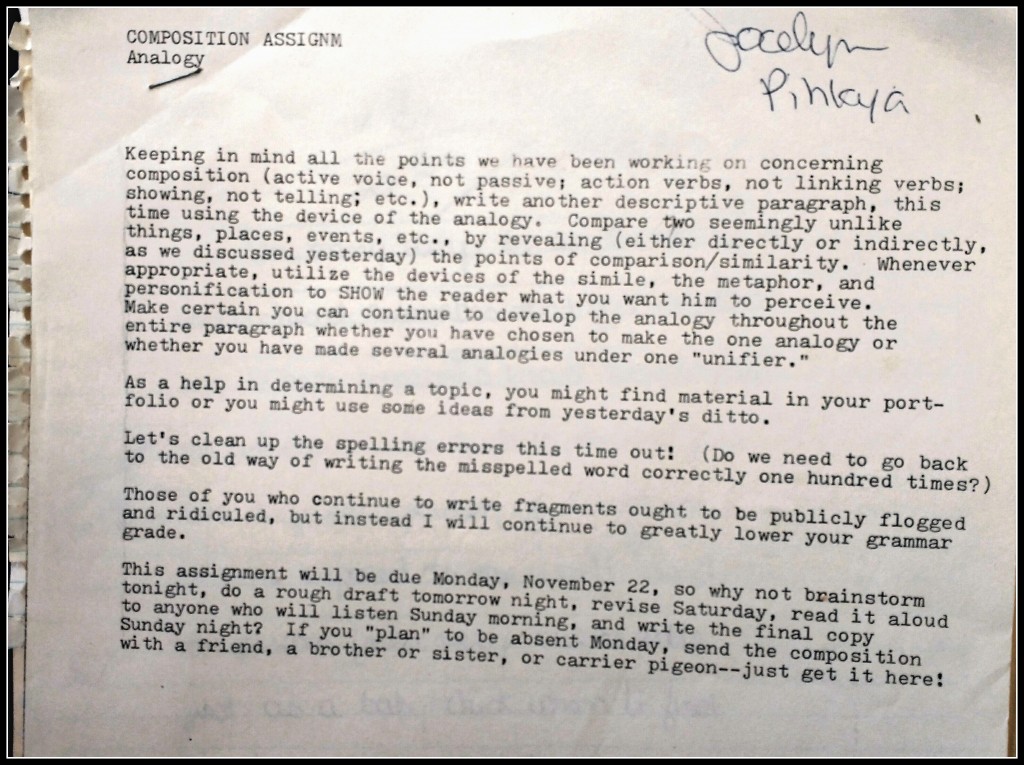

Exhibit B:

Mrs. Rice assigned an “analogy” essay.

You know you’re in an Old School English class when the light-hearted consequence for a grammatical error is violence and mockery.

I like to think I took her threats seriously and truly applied myself to the assignment.

However.

No matter how many hours I poured into it, there’s no denying: my analogy essay was and is nonsense, truly embarrassing swill.

Undoubtedly, I thought I was enhancing the broken heart/cracked egg analogy by bringing in a geyser.

Even though I lived near Yellowstone Park, I was wrong. Mrs. Rice wasn’t afraid to go off like Old Faithful and spout all over my fatuity.

The entire extended paragraph tried too hard and caused Mrs. Rice to pluck out her eyelashes, one by one, as she read.

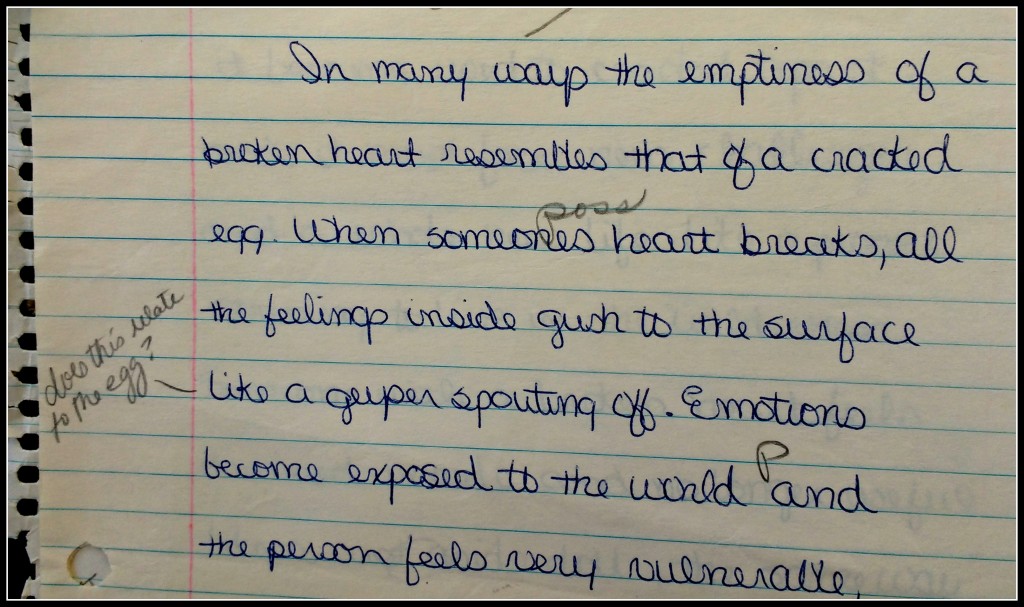

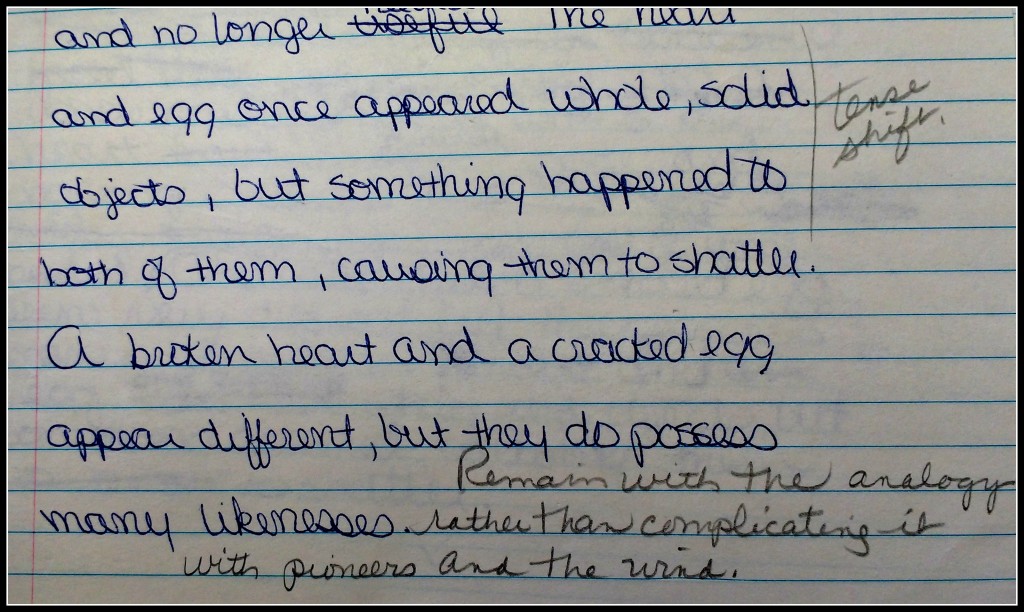

In many ways the emptiness of a broken heart resembles that of a cracked egg. When someones [sic] heart breaks, all the feelings inside gush to the surface like a geyser spouting off. Emotions become exposed to the world [sic] and the person feels very vulnerable, just as a baby chick when it first breaks out of its egg. A person with a broken heart realizes everything that he grew to depend on gets suddenly stripped away as though an angry gust of wind tore at them [sic] and through their [sic] security. A newly born chick also finds that everything it became used to cracked apart, and it must face new challenges and a whole new life like a pioneer striving to live in the wilderness. Someone with a broken heart feels drained inside and no longer feels useful like a cast [sic] aside doll, the same way a broken egg shell seems empty and no longer needed. The heart and egg once appeared hole, solid, objects, but something happened to both of them, causing them to shatter. A broken heart and a cracked egg appear different, but they do possess many likenesses.

I admit it. That’s a whole lot of crap there.

When I read Mrs. Rice’s closing comment at age 15, I’ll bet I was surprised that I hadn’t dazzled her. I mean, a broken heart being like a cracked egg? WHO HAD EVER THOUGHT OF THAT BEFORE? I WAS AN ANALYTICAL, POETIC GENIUS, RIGHT?

Not so much —

as Mrs. Rice noted in 13 accurate, spirit-deflating words at the bottom of my paper.

“Remain with the analogy rather than complicating it with pioneers and the wind.”

Decades later, reading her comment, I laughed out loud.

She had me pegged, Mrs. Rice did.

To this day, even though I still hear the echoes of her lessons whenever I try to get words out of my head and into the world, I struggle to meet Mrs. Rice’s standards.

Every single time, I start with simple intentions. A heart and an egg. Before I know it, though, a geyser erupts, the wind blows through, and the pioneers are bumping along in their Conestogas.

That’s the beauty of writing, though. There’s room for both the stickler and the dreamer. My tendencies might have caused my teacher to despair, but, then again,

maybe she needed me.

Leave a Reply