The light changes. A cover has opened, slit of sun beaming into the darkness, a ha-ha neiner-neiner taunt transmitted from the world of wind and spit. In the quick second between dandelion shaft blinking back to onyx, a gentle violence occurs, crinkling followed by thump.

A book has been returned.

***

With that thump, the movable floor inside the Returns bin lowers almost imperceptibly; a single book isn’t that heavy, after all. But then the flap clinks, signaling another, another, another, dark to light, light to dark, typeset words in freefall. Absorbing the weight of pages and ideas, springs stretch, and the catching floor gradually sinks.

It’s designed to protect the books, this bin is. When it’s empty, the floor rests near the top, quick purchase for incoming books slithering through the slot. As Returns accumulate, the floor gradually descends, earlier Returns nesting and bolstering newcomers so no volume sustains damage from a traumatic plummet.

Eventually, when enough readers have honored the socialist agreement that cooperative sharing benefits the collective, the thing is full.

It’s time to empty the cart.

***

Heavy with books come home, the chockablock bin is rolled from sidewalk through the open garage door into the space where library workers await the next scheduled curbside pick-up. In between appointments, they busy themselves with the unseen tasks — parents emptying the dishwasher at 10 p.m. while the kids sleep — that keep the place functioning.

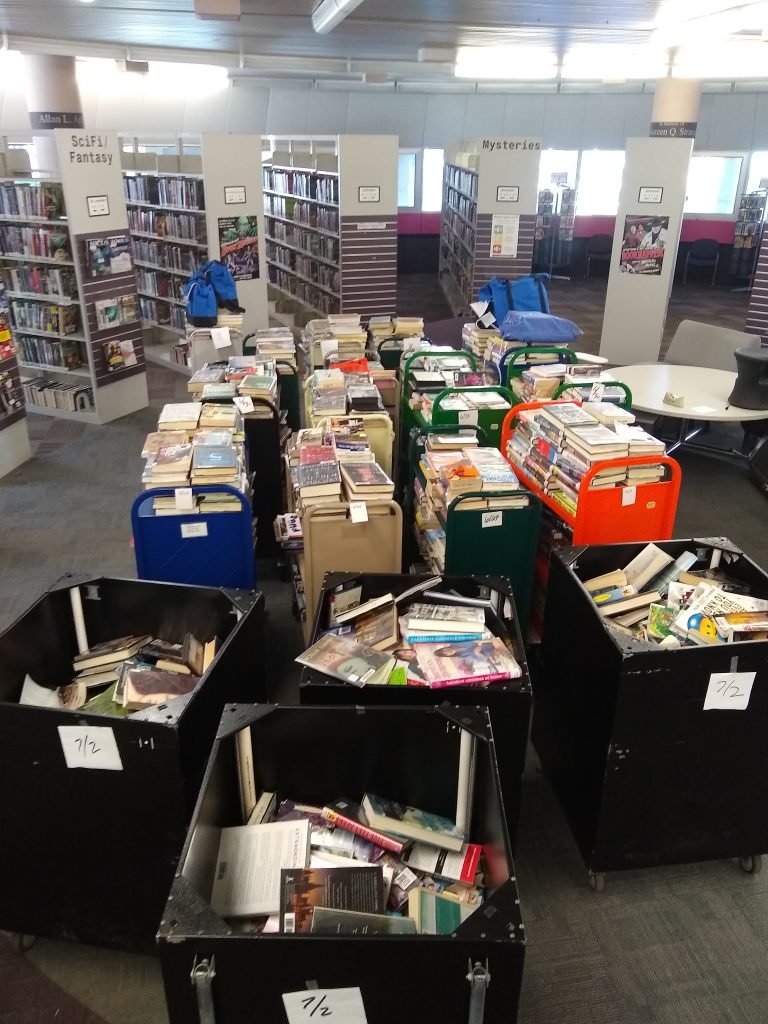

In May of 2020, it’s only recently that the library, hobbled by lockdown and layoffs, has begun to accept Returns; after months of being asked to hold onto their items because there isn’t enough staff to process even a portion of the 57,000 books checked out in the weeks before closure, fretting patrons can finally hand back the books they’ve been fostering — a permission joyfully greeted by hundreds of conscientious worriers whose pandemic anxieties latched onto the abuse that is an overdue book. With so much still unknown about transmission of the novel virus, and per Institute of Museum and Library Services guidelines, all Returns spend three days of quarantine in the bin before rejoining the organized cacophony of the stacks. The bins fill and fill, with extra bins transported from the (closed) branches, lest Returns outpace processing capability.

For 72 hours, the jumbled books hang in limbo, neither well nor sick, welcome but not admitted, the romances discreetly smoldering, poetry tautly observing, YA sullenly pouting, memoirs pointedly recounting, board books happily clapping, references clinically mapping, fantasies wildly conjuring, mysteries slyly twisting.

Laced throughout, there are murderous thrillers, their pages potentially hosting death.

***

He reaches into the bin, beginning to sort the Returns onto three carts — this one upstairs to Reference, that one to Fiction and Media, this little guy back to Youth Services. Sorting provides a kind of relief, a bit of variety to the hours, along with posing an elegant challenge: Will these six novels stack nicely and work well into the cart? Can he frame them as just-so pieces of a puzzle, thereby maximizing how many books ultimately fit onto the tiered cart shelves? Even more, there’s the satisfaction of seeing long-requested books re-entering the circle of circulation, passing from one set of hands to the next, fulfilling the promise of the communal contract.

Wait.

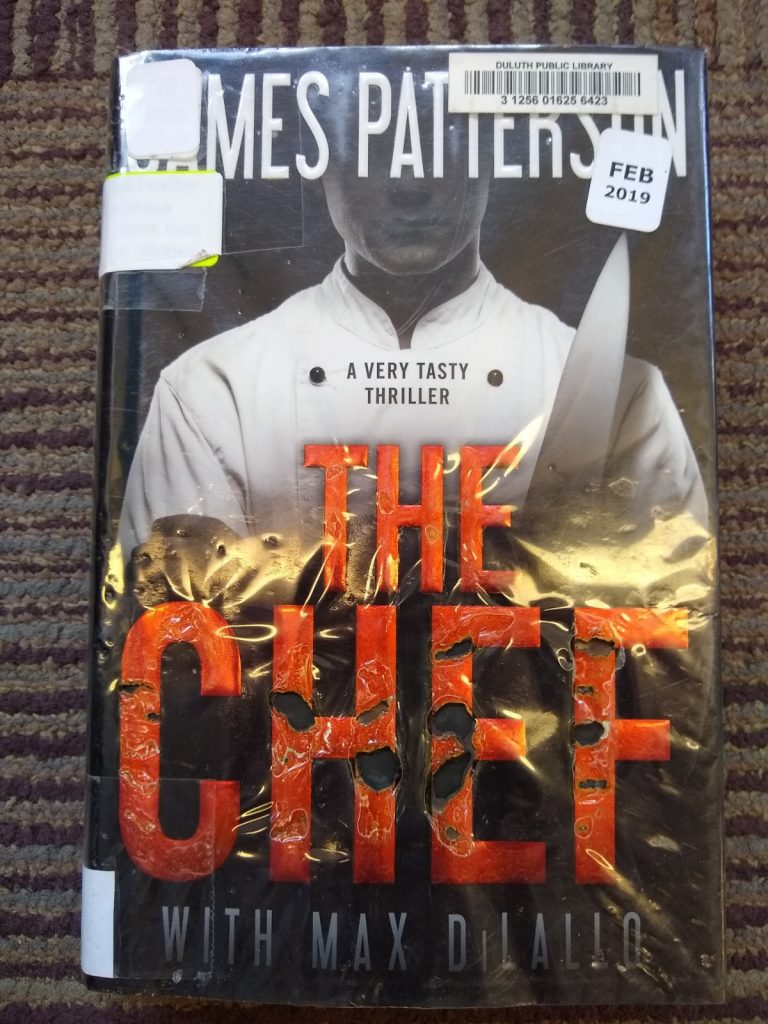

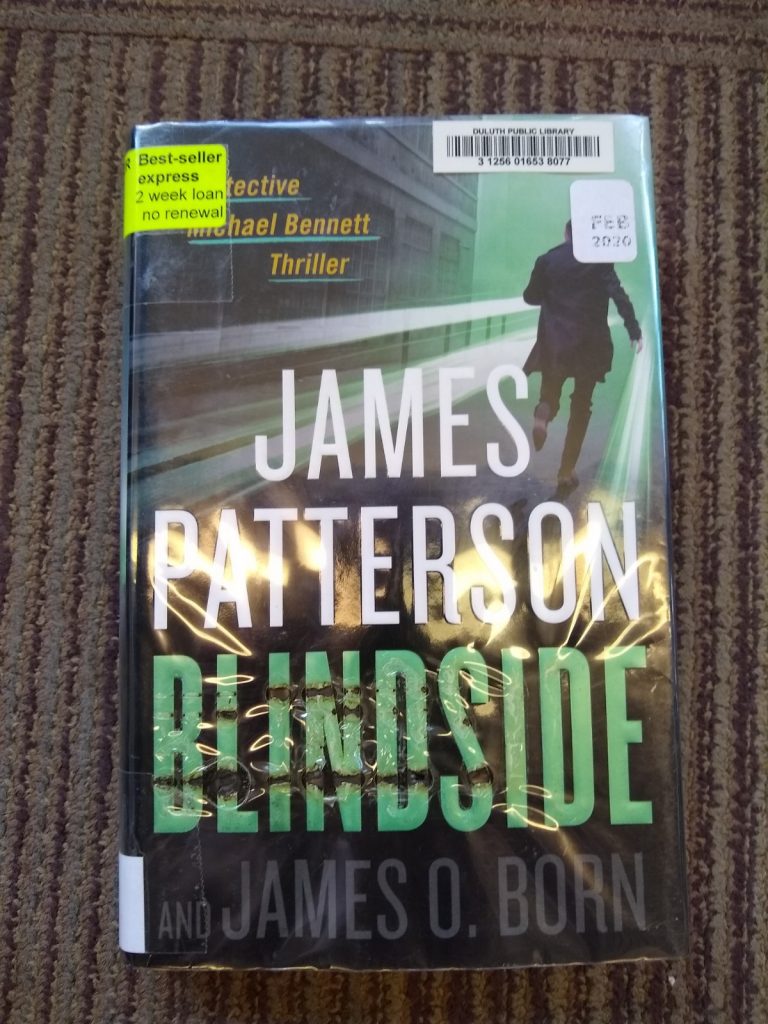

He pauses to examine the book in his hand. It’s by James Patterson. So many of them, always, are by James Patterson.

What’s going on here? Why is this plastic cover so rough?

He holds it closer, then farther away. Why are parts of this cover…melted? And why, if it’s been held to flame, is the entire cover not scorched? Has some punk with a lighter been working on fine motor skills, selectively burning spots of the book’s cover?

Confounded, reminded anew that just when he thinks he’s seen everything, there’s a surprise, he sets the damaged book aside. He doesn’t yet know who, but somebody will pay.

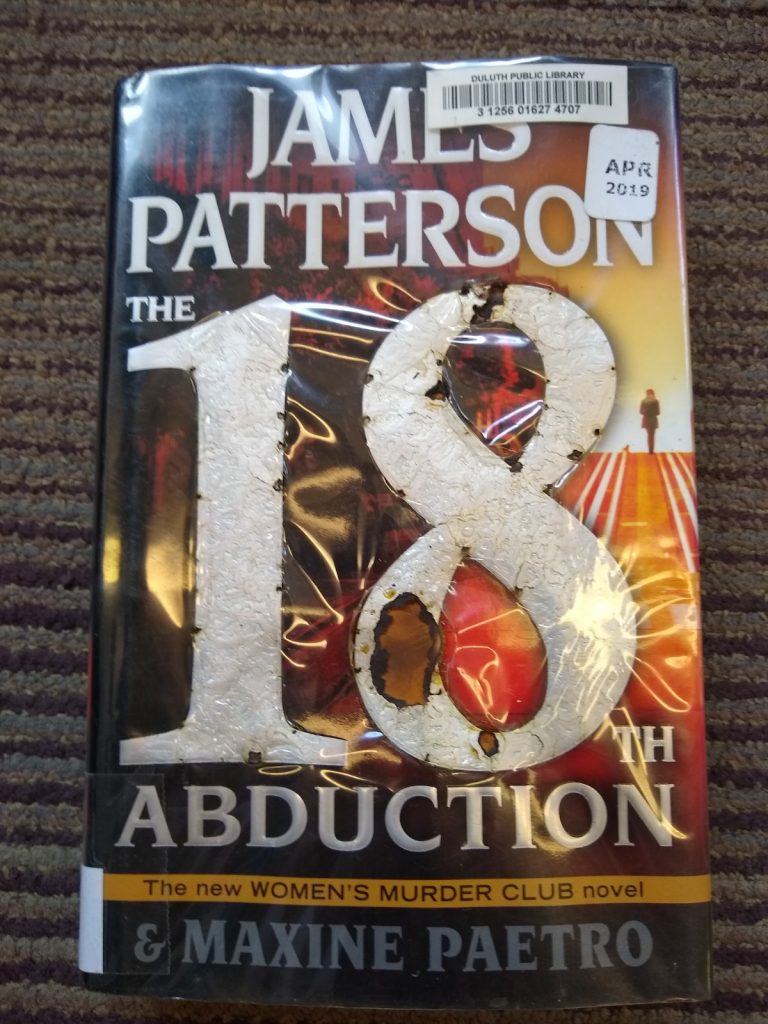

Shrugging, he reaches in and pulls out a second book from the same clump of Returns. It’s another James Patterson, this one titled The 18th Abduction, except the 18 seems to have been abducted by fire, not only melted from superficially but also burned into the cardboard of the cover.

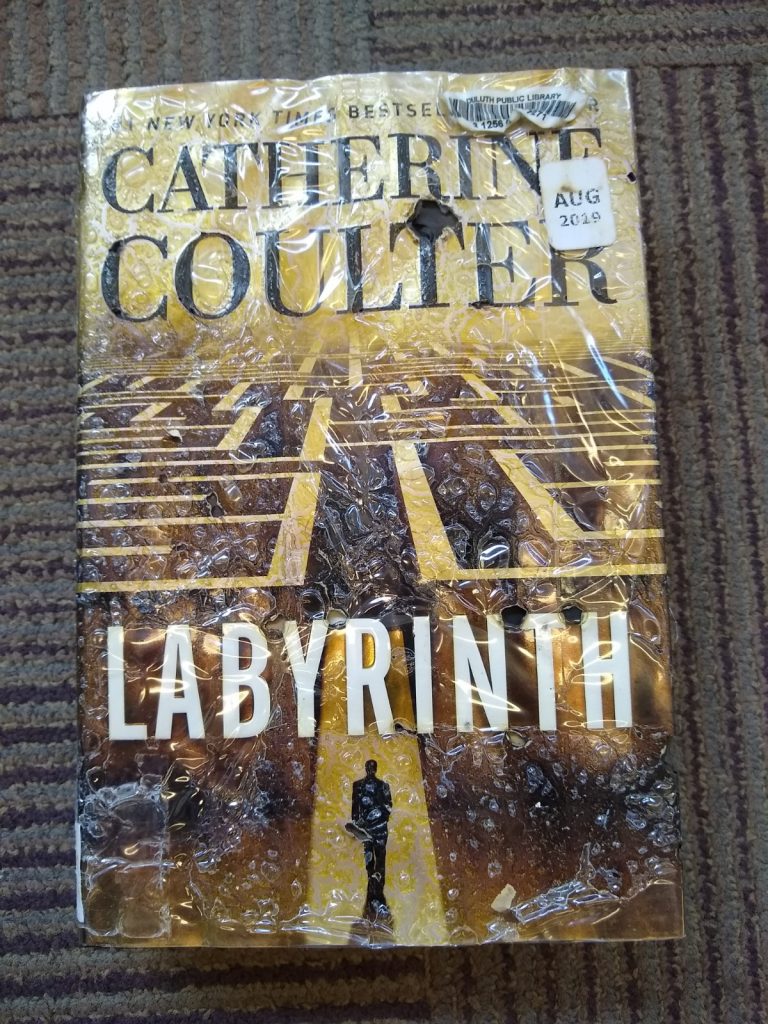

Well now. He reaches in again, pulls out a third bizarrely melted James Patterson, then, on the fourth pull, the relief of a tragically wonky Catherine Coulter. At least the arsonist patron has range.

Previously, this worker has seen a bra returned in the book drop. He’s seen a single shoe in the bin. There was the ten-inch Buddha head someone left in the library, the base of a lamp decorated with figures of stallions. He knows from experience that when a patron asks if they can borrow a pair of scissors, the follow-up question should be, “Do you want them so you can cut your nails?” This worker has loaned the library phone to someone who needs to arrange pick-up of their pet’s ashes, and he’s been told that every Minnesota state senator will be called and complaints filed if the angry patron isn’t allowed out check out books. He’s heard monologues about the surveillance tactics of gangstalking; he’s handed out Kleenex to mop spontaneous tears.

But melted book covers is a new one.

A reader himself, the worker imagines a scenario. The burning on three of the abused volumes feels deliberate since it’s focused on the lettering, so he pictures a guy in his fifties in a wood-paneled apartment, soft body flopped into a tan velour recliner, brain plagued by Covid boredom. He’s at the point where he not only spends his days in the chair; he sleeps there, too, in that stained, smelly recliner, sipping from a half-drunk can of Red Bull on the side table at 3 a.m. when he gets up to pee. He watches some shows, cruises some illicit internet sites, but mostly, there’s nothing to do, no place to go, no one to talk to. He’s read all the books — read them twice — and he’s in Month Two of lockdown, frustrated and fragile and maybe not completely in control of his impulses anymore. So he’s flicking his lighter because he smokes, of course he smokes, why wouldn’t you smoke when all the world’s a hellscape, and he’s holding, sort of slackly at first but then with purpose, one of those g.d. James Patterson thrillers, and before he quite knows what he’s doing, because he’s just lounging in his recliner like he always does, wishing for something to be different, even a little different, he’s using his Bic to develop a new craft, one involving detailed burning of public property in faintly musty private spaces.

For sure, the library worker decides as he reaches into the bin for the next book — this one blessedly unmolested — that’s what happened. Recliner Guy found a way to bring sparks to tedium.

***

It ends up being a woman in her eighties.

Perplexed as he looks at the patron information on the computer screen, the worker revises the scenario he’s already cast, deciding her black sheep son has been using her card to check out books as fodder for his craft, and now Mom is going to have to pay for the damages. There’s no way an octogenarian with delicately wrinkled topography and a lemon-colored cardigan over her shoulders even in 78 degrees would burn books.

Poor lady, having to cover her ne’er-do-well son’s vandalism. He better apologize properly, or she might need to limit his recliner time and start replacing his Red Bull with Ensure.

***

The Arrowhead Library System sends out a weekly newsletter called The Weekly Weeder. A few weeks after discovering the melted books, he’s perusing the Weeder when his eyes are drawn to an article linked from CNN.

Slowly, his eyebrows rise as he reads the words, “Please don’t microwave your books to prevent transmission of Covid.”

Huh. In a twist worthy of a Catherine Coulter suspense novel, it turns out Grandma did the damage.

Reading the article, he sees examples of books from other library systems where the microchips and aluminum antennae of their RFIDs had, when microwaved by uneasy patrons, burned through covers. In the case of his library, the melting had occurred at the flash point of an elderly, at-risk patron intersecting with foil-embossed titles. Where, he wonders, would metallic material look best on the cover of Grandma Had a Microwave?

Weeks before, when the mystery remained unsolved, the library had sent the book-cooking patron a bill. In short order — no phone calls of explanation, no pleas for understanding, no attempts to pawn the behavior off on her son — a check arrived.

The cover of Grandma Owns Her Damage would, of course, have every letter embossed with metal, the “s” a dollar sign.

***

Technically, she owns the books now. However, even though she’s gone on to check out new items (James Patterson has written 147 novels), she hasn’t attempted to arrange pick-up of the burned books.

So there they sit, stacked in his work area next to his curated Special Collection of Patron Left-Behinds:

the stallion lamp base,

a child’s bike helmet with a unicorn horn shooting out the top,

a pair of glasses from the 2017 solar eclipse when supplies ran short, and enthusiasts resorted to hoarding (perfect justice: cloudy that day),

and

seatbelt webbing fashioned into a waist belt and printed with the words THE PUNISHER.

And so, as it goes in the public library, some perfect weirdos with a complicated backstory

have found a home.

***

Leave a Reply