Introduction from Diane

First, a bit about me. I was born in Boston and spent my teenage years wrestling with an urge to get out and see the world. For almost 20 years, I’ve taught linguistics at the University of Leeds in England. In 2004, I took a career break to go backpacking and met a Turkish man. We got married, had two children, and then the marriage came to an end. Along the way I learned to speak basic Turkish and met a collection of friends, both Turkish and foreign, who are still an important part of my life. I love Turkey and go there once or twice a year so that the children can spend time with their father and his family in their village. Some of my friends there are now involved in the efforts to help the Syrian refugees living in Turkey. There are an estimated 3 million Syrians in Turkey (probably more, since many are still undocumented). Only about 10% live in the UN-funded refugee camps near the Syrian border. The rest are distributed throughout Turkey. They’re not entitled to any housing or financial support directly from the Turkish government but can get support from charities and NGOs working in the country. Most Syrian adults speak little or no Turkish, and a lot of their children aren’t enrolled in schools. This year I spent my Christmas vacation talking to people who are running projects to help the refugees. I wanted to tell their stories, the stories about what happens after the newspaper headlines die down, the stories about lives passed in years of limbo, waiting to go home or to feel at home in a place that is not home.

I first met Léonie in April 2016. Months later, we met at her house for a long chat about her work and her life. She is one of the most inspiring women I’ve ever met. The house she shares with her husband Zaki is modest and dim, and it suffers from the chronic power cuts and water shortages common in Turkish villages, but she’s transformed it into a beautifully white, ethereal, gauzy space. Talking to Léonie lowers my blood pressure. I asked her to tell me her story.

Léonie grew up in France, travelling back and forth to Greece to spend time with her Greek father. She studied Fine Arts in Paris. In art school her professors told her that her work wasn’t “arty” enough; instead of focusing on aesthetics, she was preoccupied with social issues and activism, driven by an urge to do something more meaningful. At 18, Léonie started volunteering with disabled adults, and she later went to Lausanne in Switzerland to study art therapy for 4 years. Her first professional experience was in a psychiatric hospital in France, but the civil system, with its emphasis on pills over therapy, started to kill her passion, so she left.

Léonie set off for Turkey and travelled around for a while. Eventually she encountered Mehmet, a local businessman in a village in central Turkey who had a son with Down Syndrome. She helped him set up the Shining Star Center for children with autism, Down Syndrome, and other learning and behavioral difficulties. Léonie took an alternative approach to education for these children. Using art and hippotherapy (with horses), she was able to spend a lot of individual time with the kids, and she invited other local children to the center to integrate them through play and art. It worked. In a part of the world without much support for kids with special needs, they blossomed.

During her travels around Turkey, Léonie had fallen in love with a Syrian named Zaki. An aspiring filmmaker from Aleppo, Zaki left Syria when the atmosphere became “poisoned.” He left Syria for Istanbul in 2013. His family are in Turkey (in Mersin) and have been able to support him. Zaki had studied economics in Syria, but without the right paperwork, he couldn’t transfer his credits to Turkey, and it took two years for him to be able to start over again at university. He started studying English, but he struggled with the new country, the new language and the new system. After a year, he met Léonie, “stuff happened,” and he decided to head for the village in central Turkey where Léonie was running the Shining Star Center so he could help out sometimes.

Léonie quickly realized that her work there had come to its limits, and she wouldn’t be able to achieve her goals at Shining Star. She and Mehmet fell out, and Léonie left the center to work on developing new projects with Zaki, on a smaller scale but more faithful to their values and vision. In the meantime, they found out that several hundred Syrians were living in the area, and, wanting to support and empower these displaced refugees, started running art therapy sessions with the Syrians.

I watched Léonie in action when we went to visit the center for refugees run by Open Arms in Kayseri in April 2016. The plan was to help the children create their own movie. When we arrived at the center, the place was full of people, and children were running around noisily. Our Syrian friend Ahmet acted as Arabic interpreter for the day. Léonie started by commandeering a room for the art project and building a table for a work space. She spent a lot of time creating a calm, safe space for the group of 7 boys and girls, using a minimal amount of materials. She used her quiet voice to settle the children down from the noisy chaos. When they were ready, Léonie opened the cans of Play-doh and explained that they were going to make a movie telling a story, and the story would be theirs. The children chose their characters: a lion, a giraffe, and some fish. She told them to play together with the animals for a few minutes to create a narrative. They decided to set the story next to a lake.

Meanwhile, Narjice, the director of OAK, took Léonie aside, pointing out one of the children in the group, a silent, beautiful dark-eyed 4-year old girl named Shahed. Narjice had been contacted in late 2015 about a cold, hungry family who had just escaped from Aleppo with nothing but the clothes on their backs. A Russian bombing next to her family’s house had left Shahed in shock, too traumatized and afraid to speak or make eye contact. OAK helped the family settle in to their new house with food, bedding and heating, but several months later Shahed still wouldn’t speak or interact with other children, and she screamed and cried if she was separated from her mother.

Léonie was trained to deal with children like Shahed. She didn’t bring attention to her, and she let the dynamic of the group create connections between the children. The more outgoing kids, like one bespectacled boy, helped the shyer ones to open up. Léonie didn’t expect Shahed to talk that day, but she decided to try to communicate with her using art. Shahed was playing with Play-doh. Léonie sat down next to her and started to copy the shapes she was making. Shahed started to smile, and Léonie knew they had a connection. Léonie went back to the rest of the group, and they started to work on the story for the film together. The kids were shouting and jostling to get their ideas in. Shahed sat in silence, watching them, clearly frustrated. In the end, the kids couldn’t learn the script by heart, so Ahmet read out the lines one by one, and Léonie recorded the kids repeating each line in unison. While this was going on, Léonie saw Shahed’s lips moving. Then the words came out of her mouth, and she was saying the lines with the others.

Léonie says that in one-to-one therapy it would normally take months for a child to make this much progress, but the group dynamic is much more powerful. While the kids waited for their parents to collect them, they played with Play-doh together. Shahed started to speak Arabic to Léonie. She talked about how she was making cookies and she wanted Léonie to copy her. (Almost a year later, Shahed is the happy, confident alpha child at the OAK play sessions, fluent in Turkish, and always smiling.)

When she’d finished editing and animating the movie, Léonie posted it on social media. The boy with the glasses annoyed his mother by watching it over and over again. In the story, a lion and a giraffe are walking by a lake. They’re tired and bored, so they decide to have a picnic with some fish. Then a bus arrives and takes them to Istanbul. Léonie says that first workshop couldn’t have been more perfect; the kids told their own story, the tale of a journey with a happy ending.

Léonie and Zaki have big plans. They’ve set up their own small-scale NGO called Handic’Happy, a mobile art therapy center that will travel to refugee camps and wherever there’s a need. With Zaki’s filmmaking skills, they’ll keep making movies, retro style, low-tech animated films with sets and props made from trash and found materials, like backgrounds painted onto rolls of paper that move across the screen as the narrative unfolds. (The movies are hilarious, surreal brightly-colored creations, well worth watching.) Léonie points out that making a movie is a perfect therapeutic tool for working with these kids because visual media is such a strong part of their lives. And her experience with disabled children shows how successful this approach can be.

On a recent trip back to France, Léonie did a hippotherapy film project with kids with learning disabilities using a green screen and costumes. Each wrote a different story and came up with a character. One boy with autism was clumsy and shy. He was passionate about video games, so they made a hat for him and drew on a moustache with a pen. From the moment he put his costume, he wore the character of Mario. His whole body language changed as he went completely into character, totally confident. Another boy, one with Aspbergers, didn’t like to be touched. He chose to be a robot and built a huge costume like a protective box around him. In the movie, his robot was an architect and went into the future to build eco-houses. He loved being a robot and talked about it constantly with his mother. The third boy had Down Syndrome. Obsessed with mayors, he was desperate to meet them and get their autographs. The other boys – who were autistic – struggled to work with him, but he was the powerful one in the story, a wizard. He told his mother he was a hero, and she saw him blossom into a confident child. Léonie sees her role as helping children find their voices by telling their own stories. Being stars in a movie makes them feel valuable because someone is listening to their story. They’ll remember the experience for the rest of their lives.

The way Léonie sees it, most NGOs working with refugees focus on basic needs, but therapy is also essential. She and Zaki want Handic’Happy to be itinerant and mobile so they can reach as many kids as possible. As with other similar projects, they’ll act as a service provider to get contracts with bigger NGOs. Léonie wants to run different kinds of workshops in the field to make these movies, with puppets, Play-Doh, and live action, using whatever materials she can get, with the kids choosing the characters, storyline and scenery. The plan is also to upload the movies to a YouTube channel, where the families can watch any time. For the Syrian kids, it’ll be a really important way for them to keep contact with relatives still in Syria. The refugee project will be called Nomadic Heroes. Léonie wants the kids to see themselves not just as refugees trying to survive, but as heroes of their own stories (on tv!). They’ve already overcome obstacles through creativity and resilience. Léonie sees creativity as one of the best tools in life; Nomadic Heroes will remind children that in life they’ll have challenges, but they already have the tools to meet them.

Léonie’s ultimate aim is to collect materials for a book project, a book to be written and illustrated by these kids to give them a real voice. She says, “We never sit next to these kids and ask, what happened, how do you feel about it? They might feel like puppets, and maybe their parents don’t explain to them what really happened. There’s so much emphasis on surviving, they never process the events.” For the book, she wants to work with the children to ask the questions, What is war? How would you illustrate war? Not with guns, but with something totally imaginary. Zaki comments, “The regime is about stripping people of their dignity. Their parents have been humiliated in Syria and then again in Turkey. The kids will grow up, but with what kind of model? This generation is growing up scared, without a sense of justice.” Léonie wants the kids to make this book to give them a sense of control and to give value and meaning to the journeys they’ve made. She’s looking for a publisher already and plans to distribute the book in schools to help Turkish kids understand the background of their Syrian classmates.

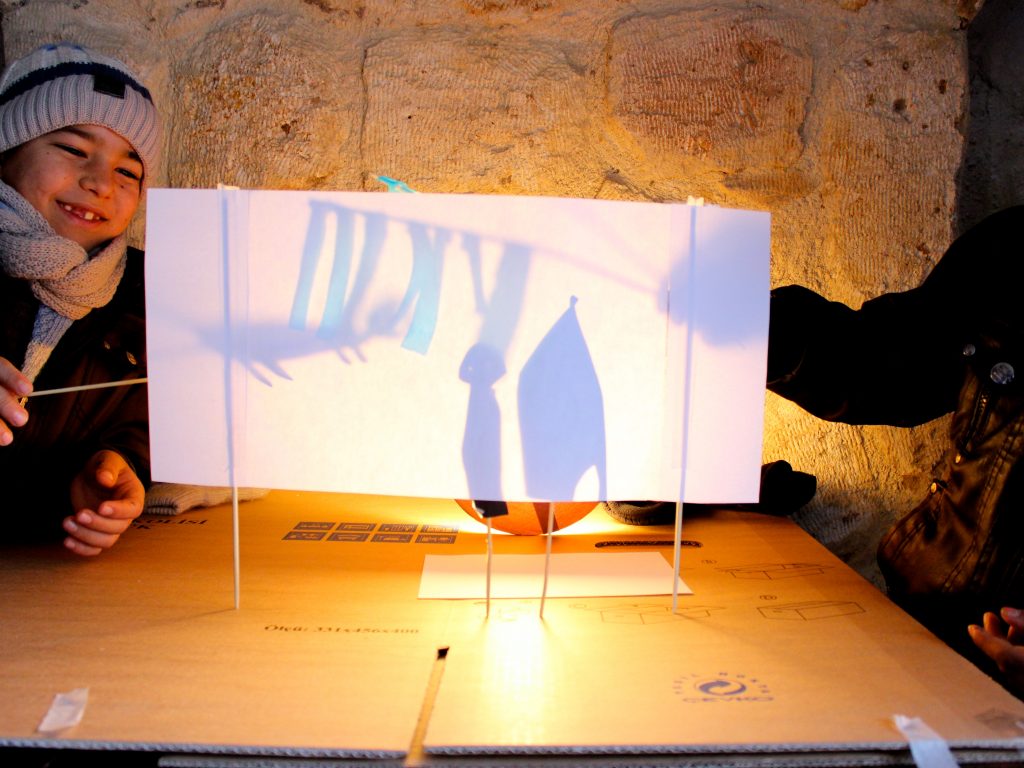

Back in the village, Léonie and Zaki have tried outaseries of new projects with the Syrian children. They’ve done drawing workshops about animals making a journey, and they’ve had puppet workshops with painted hands and shadow puppets. For the Cuddles for Syria project, Léonie and Zaki collected a donated pile of soft fabrics. The children were asked to choose their favorite textiles to design a toy, an imaginary friend, a best buddy who they wanted to comfort them when they felt upset. Léonie used the drawings as a pattern and constructed cuddly stuffed “buddies” for each child. One drawing workshop with two sisters was particularly difficult. The girls were painfully shy and too nervous to make much eye contact. A week later, Léonie gave the sisters the cuddly toys that they had designed. And a small smile appeared on their faces.

They are heroes. They have crossed to this place, and they are still alive. Soon, Léonie and Zaki will say goodbye to these children and take their project on the road.

Handic’Happy is a non-profit organization run by a volunteer team and relies entirely on private donations to carry out its work with children. They need your support. All the donations will be used efficiently and effectively towards pursuing their goals and to sustain and develop new programs that will directly benefit their participants.

You can follow Handic’Happy on Facebook and YouTube and make a donation at :

Website : https://www.handichappy.org

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Handic.Happy/

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCuES_kI6Oq7R96CK30xFklA

Leave a Reply