The whole thing took less than a second–the fleeting fraction of a second, in fact. It was a flash. A blip. A blur.

The whole thing passed so quickly I didn’t fully feel it until the next day, the day after, again today, right now, in the dark, petrified spot at the bottom of my stomach, that fisted knot of a place that sends tentacles to my lungs and yanks down hard, compressing, tightening, squeezing until I gasp to draw a breath.

In time, the thing was an ephemeral flash; inside of me now, days later, the realization of how close it was, how we almost lost them, continues to spread through my organs, a black, cold mist swirling from lungs to heart to brain, coating tissues and making sludge of capillaries. As I butter a piece of toast, I feel the fog of fear spreading again. I put down the knife, suddenly too heavy. As I type an email, my fingers freeze when the recollection catches me sideways. My message is incomplete, but I no longer remember what I meant to say. It calcifies my marrow, this fear, this memory of we almost lost them.

It happened so damn fast, the hard details have soft edges in my memory’s picture of it–a long-exposure photograph where lights have tails.

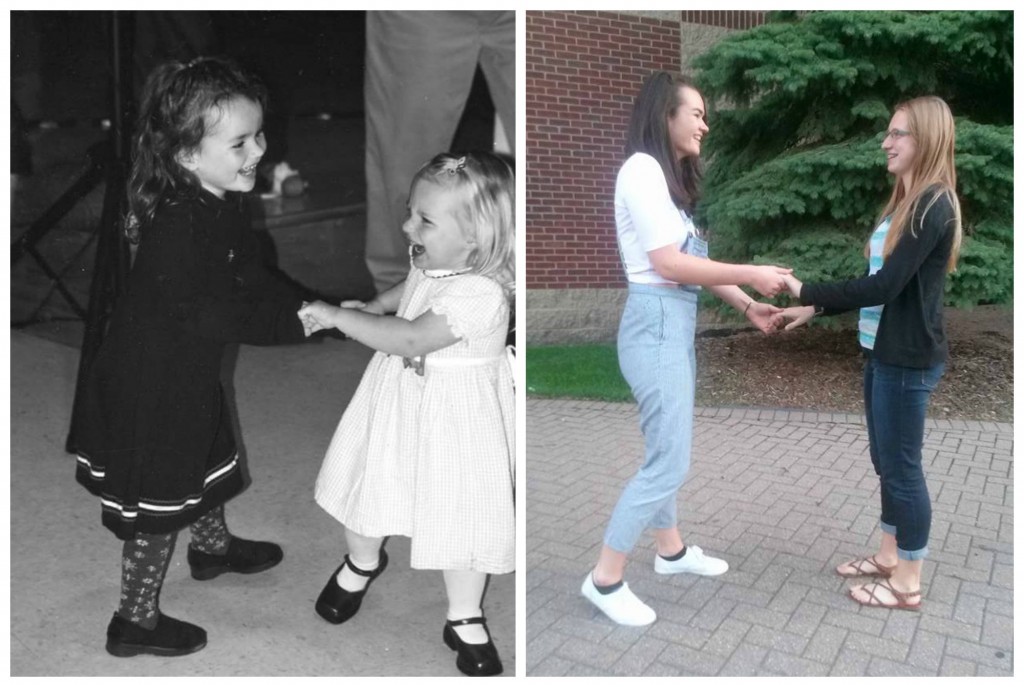

Two girls, excited and tired, walked in front of me and my husband, the four of us heading towards a waiting bus.

Then. A step. A stop. A lurch. A blur. A relieved laugh.

And we got on the bus, chattering hopefully about getting back to our hotel before the nearby late-night cookie store closed.

It was easy to gloss over the fright of that moment, moving as we were through a series of sensational events, the stuff of a hearty diary entry. The whole evening–hell, the whole weekend–had been a great boondoggle. Plans for it had started six months earlier when we’d weathered a frantic day of purchasing tickets for Allegra and Cousin Lily to attend the Taylor Swift concert in September. The morning tickets went on sale, I was the only person at home, not at work or school. I had a page of instructions from Allegra, a flow-chart of possibilities (“If there are no seats in Section 116, then the floor would be okay”). For hours, I toggled between multiple open tabs, searching and refreshing and being told all reasonably priced tickets were gone. Sold out. At the end of the school day, when Allegra came panting into the house, excited for news, it was bad.

Over the course of that evening, there were talks between the girls. How much would each of them be willing to spend? Could they bump up to more expensive seats? Yes, they could. Both girls were workers and savers. They had the money. As Allegra noted, “I don’t really buy much. I don’t need stuff. But I need to see Taylor Swift. I will see Taylor Swift.”

We got tickets. The dream would be realized.

Months passed, and suddenly Taylor was upon us. Determined to do it up right, we decided not to drive three hours home after the concert but, rather, booked a hotel room near the university. To fuel screaming and dancing, there was pre-show sesame chicken. Then, to get to the venue, we took a bus to the nearest light rail station, crossing from Minneapolis into St. Paul. At precisely 7:30, Byron and I watched our charges flow into the Xcel Energy Center along with hundreds of other white girls with too much money. Racing towards the experience of their lifetimes, they could hardly be bothered to call out a quick “We’ll text you when it’s over!”

Chinese food, public transportation, swirls of fans in tottering heels exiting rented limousines: it was more than they’d known how to hope for six months earlier. All this, and Taylor had yet to hit the stage.

When she did, she delivered everything her besotted fans could hope for. There was a gorgeous gown as she played the piano and sang a ballad. There were multiple costume changes. There was Mama Swift–clearly responding well to her breast cancer treatments!–roaming the crowd, inviting notably enthusiastic fans to a backstage meet-and-greet. Even though Mama Swift didn’t choose Allegra and Lily, SHE CHOSE SOME GIRLS RIGHT BEHIND THEM AND WAS AS CLOSE TO THEM AS I AM TO YOU RIGHT NOW AS I SHOUT THESE TYPED WORDS. That close. Even better, she looked healthy, which made Allegra and Lily’s night. They’d worried, not certain they could handle Taylor’s grief if her mother were taken from her.

Their rundown after the concert, as we all lolled in the lobby of the glorious St. Paul hotel together finishing our drinks (Maker’s Mark for Byron, Riesling for me, Sprite for the girls), was reminiscent, in its enthusiastic investment in a beloved celebrity’s minutiae, of how anxious I used to get about the relationship between Shaun and David Cassidy, two legendary talents who never quite gave off the vibe of being each other’s port in a storm.

These things matter.

…especially when you’re 15 or 16, and everything outside the routine turns of daily life–everything beyond lockers, smelly gym clothes, and the heft of an Honors Biology book in the backpack–feels like a glimpse of a possible future, a whiff of When Life Really Starts, a taste of the endless possibilities that can mushroom from energy and smarts and imagination.

When we love a pop star, we believe, very cleanly, in something, and that’s powerful magic, particularly during a stage of life that can be oppositional, driven by a need for separation, mobbed with infinitesimal slights and cuts.

That’s why, as we four sat in the lobby of the fancy hotel near the Xcel Energy Center (more than likely the hotel where Taylor herself was staying), I was completely happy. Not only was my stomach full of sake, udon noodles, and pickled eggplant from the special “date” dinner I’d had with Byron while the girls were at the concert; not only was there a huge bag of nummy popcorn in a bag under the table, bought at the Candyland store near some of the Charles Schultz-inspired statues littered around St. Paul; not only had Himself and I enjoyed a lovely wander around the downtown, stumbling across live music, craft beer, and a Saints baseball game during the ritual sing-along; not only had this evening been perfection for me and Byron, it had been perfection for the two girls who had been squealing “I’m so excited!!!!” for months –or, in Allegra’s case, smiling gently, which is her equivalent of “I’m so excited!!!!”

As the girls squished together into an armchair upholstered with burgundy velvet, the backdrop of a marble fireplace framing them, watching hundreds of fans staying at the hotel wait in line for the elevator, showing off the merchandise they’d bought at the show, the evening was complete.

Taylor had been awesome. They loved her. They were awesome. We loved them.

Eventually, yawning, we headed towards the light rail station. Perching on a ledge out of the wind, huddling hip-to-hip as we waited, Allegra and I warmed each other. When the train arrived, we hopped on, enjoying the mostly empty cars. After a handful of stops, it was time to get off and transfer to the bus. Normally, the light rail extends all the way to the station near our hotel, but for this one weekend, the last leg was closed, and we had to use the bus. Even though it was midnight, a public transit worker waited at the station, waving those of us exiting the train over to the idling bus across the street. The man in front of us, worried the bus would pull out before he got there, started jogging, his pack slapping his back. We, too, put a hustle in our step until we heard the worker call “No need to run! It’s waiting for you.” Slowing a bit, we were still in thrall to the momentum of the man in front of us racing towards the lights of the bus.

He dashed across the street. Talking, caught up in our bubble of four, absent-mindedly following our fellow train traveler, we weren’t paying full attention.

Then. A step. A stop. A lurch. A blur. A relieved laugh.

In front of us, the girls had very nearly stepped out into speeding traffic. Six inches away from a car hurtling by at 40 miles per hour, they halted. Some instinct stopped them, and they leaned back, their hair billowing as it raced past.

The whole thing took less than a second–the fleeting fraction of a second, in fact. It was a flash. A blip. A blur.

Collectively, we absorbed the near miss, our bodies hissing a quick “whoa” before we carried on. Talking. Walking. Catching that bus.

As we neared the lights of the bus, I whispered to Byron, “That was really close, what just happened there.”

Two words were enough: “I know.”

Clambering aboard the bus, we rode to the hotel, watched some Kardashians, brushed our teeth. The next morning, we checked out and treated ourselves to bubble tea before driving to a northern suburb for a stop at Target and Trader Joe’s. The sense of a heightened weekend continued at these places, where Lily randomly ran into her uncle and cousins and, even more startlingly, a two-headed woman was sighted near the underwear section, again by the office supplies, once more at the checkout. Ever on the mission, Lily lifted her phone close to her face and whispered, “I think she was on a tv show. I’ll google it.”

Feeling amused by it all, we–a foursome in tandem, almost by rote at this point–meandered across the parking lot, across the road, to Trader Joe’s and Chipotle. There had been Taylor; there had been a two-headed woman; there would be burritos. After a weekend such as this, we would return home flushed, beaming, renewed.

Of course, something else had happened. Or, rather, not happened.

As we walked, Allegra bumped up against my shoulder and commented, “I keep thinking about last night.”

“Yea, you’ll never get over that concert, will you? Big stuff,” I responded.

“No. Not that. The part with the car. Where it almost hit us. How we could have died.”

Prickles. Scalp to toes. Prickles.

I hadn’t been sure the closeness of that call had fully registered with her.

It had.

She continued, “I mean, for some reason we pulled back, and it was okay, but that car was going really fast, and it was so close. It was so close and going so fast.”

It is the rarest of gifts, to be able to talk to your child about how she didn’t die. “Yea, Leggy, that car blasted by, and none of us really paid attention to the traffic–partially because we were following the other guy from the train, partially because our brains were floating around happily, and partially because there was that kind of guardrail-fence thing there that made us feel protected and separate. But I have to say this: if you hadn’t leaned back, this would not have been a case of you being badly injured or even disabled for the rest of your life. If your feet had been a few inches further out, this would have been a case of absolute death. I keep seeing it in my mind, and it freezes me inside each time I think about it.”

Quietly–of course quietly because that’s her–she agreed, “Yea. Me, too. We would have died.”

Then, wryly–of course wryly because that’s her–she added, “But at least I would have seen Taylor Swift before I died.”

Laughing, I wrapped my hand around her waist, and, together, we walked towards the next thing.

————-

Leave a Reply