I went to a baby shower last weekend. Although it got a little woo-woo during the programmed portion of the event (a candle was lit in the center of the circle; we all held onto a long hank of yarn, one that apparently connected all our pulsing womanhoods into one larger life force; there were beads; there was sharing), I managed to stifle my desire to make a break for the door. This was a good thing, as conversation, once the compulsory estrogen communion was over, returned to an unorchestrated flow, during which Knocked-Up Friend noted that, because her IVF baby had been created quite deliberately, with the help of a village of medical types, and because the pregnancy was iffy, what with her being a fairly aged crone of 40, she hadn’t shared news of her pregnancy right away…but when she did go public, she expected the world to gather around her in a seizure of delight, making continued hoopla at her feet for the remainder of her nine months of maternal glow.

What a shock it was to her, then, to finally publicly join the ranks of the preggers in a prenatal yoga class. She entered the room, secure in the knowledge that she was the cutest pregnant woman in Duluth, only to realize that there were 10 other equally cute pregnant women there, all contorted into lotus position. The following week, when she went to her first birthing class at the hospital, her illusions were further snapped when she stepped into a room full of another 15 really cute pregnant women, all of whom inhabit Duluth. It appeared that the title of Cutest Pregnant Woman, with all its accompanying bling, glory and ballyhoo, would have to be shared with every other damn big-bellied woman in the Twin Ports region. She would not, to her dismay, be the sole Gestational Goddess in town.

The same lesson was pounded home to me five years ago, in the summer of 2002, when I was pregnant with the Wee Niblet. His being my second pregnancy, and with a very charming 2-year-old scene stealer already living in the house, I wasn’t actually under the delusion that I was the center of anyone’s universe, but, still, I was imbued with that special pregnancy feeling that I carried in my womb a profound and secret joy.

Then one day, as we awaited the arrival of my mom and her sister who were driving to Northern Minnesota all the way from Rectangular States to the West, the mail arrived.

And in the mail was a personal letter. How lovely to get a personal missive in the age of postal-service-whore-as-pimped-by-direct-mail!

Strangely, the letter was from my mom, who’d been on her way to us for days. She must have posted it just before she hit the road.

Assuming it would contain her usual “I saw this little snippet in the ‘Humor in Uniform’ section of READER’S DIGEST and thought it would make you chuckle” contents, I carelessly ripped open the envelope.

The first sentence read “The topic of this letter may surprise, even shock, you.” By the second sentence, the alveoli in my lungs filled with sludge, and breathing became difficult.

There I was, 35 years old, up the duff, about to become a child of divorce.

Naturally, my grades in school would slip due to all the hookey I would be playing as a result of my need to act out, a consequence of my feeling that my parents’ break-up was all my fault, which would mean I’d probably be hung over the day I took my SATs, and I’d never gain admission into a spendy private liberal arts college!

Or, more accurately, what with my advanced age, maybe I’d start refusing to clip coupons, pay taxes, and shovel the snow off my sidewalk after big storms. That’d drive home to dear old Ma and Pa the depth of the damage they’d inflicted!

My immediate reaction to this announcement that my mother had filed for divorce from me dear da–and informed me through mail in the age of telephone!–was, “What if this letter hadn’t arrived today? Mom will be here in an hour. Would she have gotten out of the car, sized up my body language, and then just fished around (‘So, how’s GrandGirl? Your pregnancy going well? Get any interesting mail lately? Great weather here by the lake!’) until it became clear that I didn’t yet know? And then, tomorrow, when the mail is delivered, would she excuse herself to the bathroom until the rustling sound of papers stopped, and the sound of bereft wailing began? Then she’d know I had read her note, and she could emerge from the bathroom, asking again, ‘Get any interesting mail lately?’”

But I got the letter that day, just before her arrival. I started sobbing immediately. An hour later, when she and my aunt pulled up in front of the house, I marched outside, grabbed her in a big hug and said, “I can’t pretend any niceties here. I just got your letter. And I’m so sad.”

“I am too,” she responded, falling into my arms. The rest of that night saw us on the couch, talking through this earth-shattering move she’d made.

To summarize my mother’s feelings: my father was not an expressive or demonstrative man; for forty years, she had felt unloved; she had tried to communicate her distress to him, but nothing ever changed; she had decided she’d be better off living alone than living with someone yet feeling so lonely.

I got all that. What made for a delightful and consistent father did not necessarily add up to marital bliss. I got it.

During our couch therapy that night, I told Mom that no one could find her happiness but her, and no one could go after it but her. So she should do what she needed to do. I also told her I was sorry for the pain she’d gone through all those years and in coming to the Ground Zero that signaled her readiness to make things change.

We pretty much ended up having a nice visit.

And yet.

I felt broken for my father, a quiet, gentle Finn defined by his reserve and thoughtfulness. I felt broken for his lack of representation during The Airing of the Grievances. I felt broken because his health was dismal, and he was 67, and he now faced his Golden Years alone. Personally, I felt broken because I’d just discovered, waaaaaaaay after the fact, that the story of my growing up years was a myth–I hadn’t actually grown up in a reasonably-happy, well-adjusted household but rather in a house of ache and missed connections and settling. Good thing I had been too busy watching re-runs of THE BEVERLY HILLBILLIES to notice any genuine human pain loitering there in the kitchen.

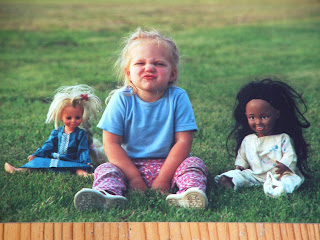

And on some level, I was broken that the child growing inside of me would never bask in the heady collective adoration of Gampy and Gammy. He would never sit between them on a porch swing, or on a couch, encircled by their palpable affection. There would be no circles of love at all, just straight lines between individuals.

After my mother’s visit, things got very sticky very fast. Mom and Dad continued to live in their house for another couple of months, until Mom moved into a little apartment and Dad into an independent-living home for seniors. We visited them during those last weeks together in their house, popping in on our way back to Minnesota from a wedding in Colorado. We brought with us a friend who was about to move to the Pacific Northwest, a friend who needed to outfit his new kitchen. And I’m here to tell you that, if you ever need to outfit your kitchen, stopping by the home of divorcing people is a pretty good strategy. They each are sure they need only one plate, fork, and glass. The rest? Friend can box up and take to his new life of friends and romance.

Staying in that house was tense. Awful. I didn’t know who felt how, who had been a part of which discussion, who needed help, or who didn’t want me to splinter a brave facade.

Then the news slipped out that my mom had actually been seeing someone else–not a physical affair yet, but an emotional one, made up of letters and phone calls exchanged behind my father’s back.

Gentle readers, my parents were church people. They had, under the banner of heaven, judged others for moral failings. They had, in the way of organized religion, pulled self-righteousness around them like an L.L. Bean Barn Jacket (color: Sandstone Pyramid; size: Extra Large).

Don’t get me wrong: my parents had always been tolerant, inclusive people, in terms of a worldview. But the soap opera aspect of my 67-year-old mother striking up a relationship with a guy she’d gone to high school with–and without ever telling my dad (that eventually became my job, when he questioned me directly, as did telling my brother and sister; my mother then asked what their reactions had been. Er, not so good)–was the most unexpected. Who knew our sleppy little hamlet of Pine Valley had been rife with divorce and infidelity and anger all those years? Suddenly, that summer, it seemed no one was without sin.

Well, except my dad, unless consistently trying one’s hardest is a sin. In the middle of all the ensuing stone throwing–my mom towards my dad (she needed to do that to work up the courage to follow through and to rationalize her right to do what needed no rationalization); my mom towards us kids (creating wounds that will never heal); us kids toward my mom; in some instances, us kids towards each other–the only one who never picked up a rock, the only one who wished fervently that everyone would just back off the hail of pebbles, was my dad.

Even though he couldn’t give my mom what she needed, he was the best of men.

Before my little family quit that tense visit in Montana, we spent a morning driving around Billings with my dad, having me added to all bank and legal documents as his new co-signer, since he would no longer have a wife. At the end of our trips around town, we stood in a bank parking lot, trying to find the right way to cap off seing each other in such a bewildering, foreign time. Before that day, I had seen my dad cry once before, at his mother’s funeral. In the parking lot, for the second time, I saw, felt him cry, as he came into my arms, and I held him against my thumping belly. He sobbed and sobbed. So did I. So did the onlooking Groom. Girl pointed at birds in the sky. He sobbed on. Finally, all I could whisper in his ear, so conscious of his unflagging reliability, his dependability, his constancy, was, “You deserve better than this.”

They each moved into their new, separate homes in early September. My brother, in the military and assigned to a base in Japan, flew home to help with the monumental garage sale and to march them each to a financial advisor. During that time, Mom took her new relationship to a deeper level. Dad, an extreme introvert, ate in a cafeteria, amongst strangers. He made plans to buy us a larger house in Duluth and to take over living in our smaller one, to ease our double mortgage plight.

Then, one night in November, he called 911, complaining that he couldn’t breathe. That was the last time he lived in a home, such as it was there in the senior center, his “home” of two months. That was the last time he wasn’t being ministered to by unfamiliar, clinical hands, save my sister’s. That was the last day his life held anything like predictability.

For the next three months, he was in the hospital, being discharged only briefly to rehabilitation facilities before re-entering the hospital. As his lungs and heart declined, we had some close calls, a scary night of intubation and the doctor on the phone with me at 11 p.m., telling me to call my siblings.

But he recovered enough to still have hope of returning to a life of regularity. During all of this, I was unable to travel due to an impending due date, and my brother was across the world in Japan. Heroically, and I don’t use that word easily, my sister single-handedly walked with him to the grave, using up all her vacation days plus some, driving and flying back and forth between Denver and Billings, sometimes twice a week. She may have her foibles, as do we all, but I’m never forgetting how capably she carried him for all of us.

Three months after he first called 911, my dad died. On that morning, at about 5:30 a.m., he was in his first full day at a new rehabilitation center, and he had called in a worker, a stranger, to ask for help turning over. In that action of turning over, his last gasp was forced out.

And that was it.

My sister was in Denver.

My brother and his family (my sister-in-law seven months pregnant herself) were in the middle of the long trip from Japan to Montana, having realized the now-or-never nature of his decline. I reached them by phone during their layover in Detroit and broke the news. I’ve never been part of a more horrible phone conversation, and I’ll never forget my sister-in-law’s voice in the background, keening, “What do you mean he’s dead? How can he be dead? But we’re so close.” And over that, I heard the voice of my niece, my dad’s first grandchild, then five years old, questioning, “Grandpa Don is dead? Daddy? Daddy? Is Grandpa Don dead? Daddy, is your daddy dead?”

I, having just given birth to Wee Niblet during the worst day of my life on January 17th, was in heavy recovery. And then the date of the worst day of my life changed. It became February 2nd, the day my daddy died.

So this man–who lived out his life a mere 40 miles away from the ranch where he had been raised, who taught at the same college for 35 years, who was a fixture in his recliner–died, alone, amongst people who had to check a chart to call him by name, in a room that had been home for 12 hours. That will always slice me in two.

My enduring grief over the nature of his death is assuaged a bit when I remember that, although he never saw the Wee Niblet in person, he did get to see pictures and did have a chance to tell me how proud and overwhelmed he was to have such a lovely grandson (and, in his typical generous fashion, he offered to send a cheque so I could hire some “help” during my torturous recovery from the delivery).

I don’t know if there is a heaven, but I know now why people need the notion of one. If there is one, my dad is there, in his easy chair, listening to choral music directed by Robert Shaw, surrounded by photos all four of his grandchildren, photos that show them thriving and embraced by love.

Indeed, my dad didn’t get his happy ending.

My mom’s still working on hers.

—————————————

So, you see, my second pregnancy wasn’t at all about me.

Leave a Reply