I knew it was coming, so I’d had a couple days to brace myself.

I knew it was coming, so I’d had a couple days to brace myself.

Mostly, my strategy was to hide upstairs, answer the occasional question, and deliberately pour my soul into a zen acceptance of chaos.

Actually, now that I reread that previous sentence, I think I might ask Byron to stitch a version of it into a sampler with the heading “Tips for Parenting Teens.”

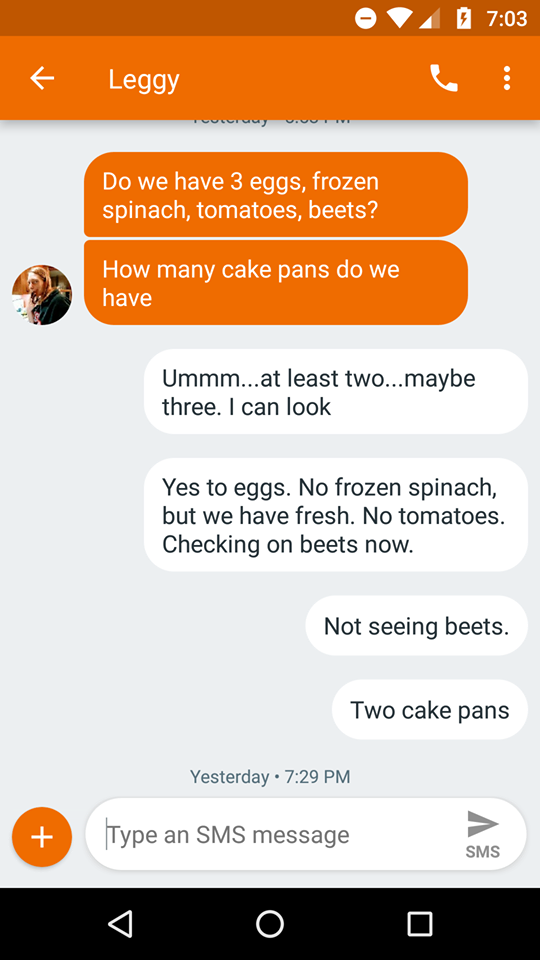

So I knew Allegra and two friends had decided to make dinner at our house Sunday night and that our girl would be calling me after she was done with work and when they got to the grocery store, to ask about items we might already have in stock at the house. Because she is well raised, it was a text, not a call, that came through first. Cake pans. Eggs. Spinach. Tomatoes, Beets. Well, this sounded promising. I knew the plan was to make tricolor pasta from scratch, but BEETS? Nice, ladies. Nice.

A few minutes later, my phone rang. It was Leggy. Stabbing wildly at the screen, I managed to refuse her call as I tried to answer it. Calling her back, I opened with, “So, yeah, I have no idea how to answer my phone. Like, truly. I was trying to answer it. As of tonight, my record for failing to answer all calls is intact.”

Oh, she felt me. Why should anyone know how to answer a phone when phone calls are the devil’s work? We shared a silent moment of mutual understanding that felt like a warm hug. Phone calls. Fuck ’em.

Anyhow, did we have cocoa?

And so it went. A short time later, I heard the girls come into the house, a rustle of bags and giggles in the kitchen. Adhering to my planned strategy, I stayed upstairs and let them figure themselves out.

Except, then, after a relatively quiet twenty minutes, the top of Allegra’s head rose on the staircase. “Where’s the pasta maker?” In the basement pantry.

Some bit later, I heard the squeaky crank of the pasta maker’s handle. Dang, but something in me is wired towards squeaky cranks (see: the boyfriend of my twenties). I wanted to go down. Take a peek at how it was going. Watch them crank. But nah. If this was their deal, it should be their deal.

As I kept myself busy at the computer instead of tromping down to ask dull questions and provide overly perky commentary to their actions, I thought about the teenagery-ness of wanting to make three different pastas from scratch when those same chefs had never, say, made spaghetti from a box and red sauce out of a jar all on their own. Although I had tried earlier to suggest there’s no pride lost in opening a box of noodles, my words fell on 17-year-old ears. “But we want to make it from scratch, and we want three colors! Also, we want to make a cake!” From a mix? “From scratch!”

I commend the attitude and the values behind thoughtful, non-instant cooking. Yet, at the same time, I was amused by the desire to take on big goals before mastering smaller building blocks. Although I was chuckling at their ambition, I admired them for it — ah, that glorious stretch of years when anything seems possible because everything is still possible, so why not go big? That confident mindset is something that life’s vagaries can erode; no need for me to act as an instrument of deflation. Hell, when I was about 15, having never before cooked a reasonable pan of brownies, I told my mom I wanted to make a Baked Alaska because I couldn’t believe ice cream could go in the oven. To her eternal credit, my mom’s answer was, “Let’s do it.”

Baked Alaska is really cool, y’all. I haven’t made it since I was 15. But I know it’s cool because I lived in a house where ideas were welcome.

In addition to confidence and ambition, these teen girls have humor. When Allegra first announced they would be making dinner, she laughed when I replied, “So we should plan on eating around 10, then?”

“Well, last time we did this, it did take us five hours, so yeah, it will be late. You should make some eggs for Paco so he doesn’t get crabby,” she nodded. “But, I mean, last time we did make homemade fettucine and sauce and noodles and soup and salad and bread and pie, so it was understandable that it took us five hours.”

Please, for the love of James Beard, girls, stick to tricolor pasta and a cake. Don’t go getting notions about a protein, I prayed.

In the kitchen, the squeaks and shouts continued. Then, through the banister railings, Allegra’s head rose again. “Do we have more flour?” Yes, downstairs in the basement pantry, by the Fischer-Price village.

Although I’d been following my strategies like a boss, a look at the screen told me it was Shot of Scotch O’Clock. Could I maybe contribute to the evening’s memories by being the mom who only showed her face when in search of booze?

Bravely, I headed down.

Well, now. Things were happening. Allegra was separating threads of tomato noodles while Natalie worked spinach dough through the machine. Elizabeth was on frosting duty, except

“Mom, do we have more butter somewhere?”

Yes, down in the basement in the freezer. Here, let me get it.

A moment later, a pound of frozen butter in hand, I suggested they might want to soften a stick in the microwave on low power — or, alternately, “Jam it into your armpit, honey.”

“Hey,” Allegra said. “That’s what I did earlier, and it worked great!”

Leaving them to the softening, I headed upstairs.

Forty-five minutes later, the pasta maker still cranking, I decided a glass of wine might be in order, what with dinner being a distant hope. This time when I got to the kitchen, Natalie decided her arm was tired, so Allegra took over; in return, Natalie tucked the stick of butter under the front of her shirt, nesting it at her waistline. Within minutes, her chi had made the stuff malleable. In one corner, beet pasta covered the counter. In another, chocolate frosting came to life. Duties were traded and handed off, and somehow, synergistically, the food was happening.

Back upstairs, I recalled the time my sister, some other neighbor girls, and I decided to make a special summer lunch for some of the neighborhood boys. After finding them at Mike’s house, we told them to come to our house in an hour for some good food. Minutes later, having scrambled down the hill into our kitchen, we had water boiling for a box of mac ‘n cheese and a pan heating for hamburgers.

Mostly what I remember about that afternoon with “strange” boys sitting at our dining room table is that I felt special — that we girls had presented ourselves as capable and domestic…in some bizarre hope of gaining a boyfriend? — that our efforts proved our value.

Because life is beautiful, a dynamic thing allowing for change and growth, I would, thirty-odd years later, accept a social media friend request from the lead boy on Hamburger Day and then, less than a week later, unfriend him, thinking, “I can’t stand you, and I can’t see why I need to pretend otherwise.”

Eventually, Allegra’s voice rose up the staircase again, this time with welcome news, especially for her brother who had been on a school bus at 6:45 a.m. that morning, heading to a robotics meet in another city. Even though he was dubious about the potential of tricolor pasta, he was, at 10:30 p.m., both hungry and ready to sleep.

“The pasta’s ready!”

Whew.

“Stay on your bed, kid,” I told Paco. “I’ll bring you a small bowl, and if you like it, you can have more.”

By the time I got to the kitchen, the girls were loading bowls for themselves, apologizing about the noodles (“They just taste like pasta, not like spinach or beets or tomatoes”); apologizing about the sauce, which they had made up once they realized they were missing Alfredo ingredients and had refused my offer of a frozen red sauce (“It’s kind of, um, weird. We just put Parmesan, butter, cream, and some leftover tomatoes together”); exclaiming about how much pasta they’d made when I told them I could boil up some more if they wanted to finish what was in the pot (their idea of “a lot of pasta” was modest); wondering where they should eat (the kitchen being inhospitable due to every possible dish and utensil having been used during the cooking, the dining room table full of Paco’s toothpick bridge he’s making for science class); and thinking it could be good to watch some DVR-ed Olympic skiing while they ate.

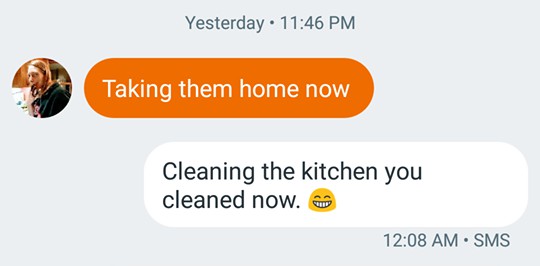

After a quick primer on how to navigate through Hulu using our Fire stick remote, I left them to enjoy their tiny bowls of noodles, big pieces of cake, and admiration of the skills required by biathlon. Back in the kitchen, I tried to keep my sigh inaudible. They. had. trashed. the. place.

I had known it would be a mess, but they had exceeded my expectations. Were I a set designer for a sitcom, and were it my job to stage a helter-skelter kitchen scene because — haha! — Dad had tried to cook, I could not have come up with what these three high school girls accomplished organically.

They had noticed the mess. They had said they’d clean up. They needed to be the ones who cleaned up.

But still. As long as I was there, before I scooped noodles for the boy and me, I just had to put a twist tie on that open bag of confectioner’s sugar, tuck it into the drawer, put those oven mitts away, collect the five empty butter wrappers, and stick the flour container back in its nook.

There. I did ten things. The rest was up to the girls.

From the next room, the easy, happy energy of three young women — longtime teammates — watching skiing and eating food they had made “just because” washed into the kitchen. I tucked and threw and stuck, and I was hungry, and I was afraid of the clean-up they would do, but, oh, I felt complete.

In every dream of my future back before I knew the shape my life would take, the kitchen was filled with light and noise, filled with the cacophony of friends coming together around food and communal creation.

As I walked up the stairs with pasta and cake ready to hand to the sleepy 15-year-old, I thought about my childhood friend, Lisa. She lived next door and was a constant playmate and companion, often staying with our family when her parents would take junkets to Vegas to gamble. Even as adolescents, Lisa and I would sleep head-to-foot on my waterbed, and during the days when we were hungry, and there were no moms around to feed us, we would make our favorite snack.

Pouring one cup of white rice into a pot, followed by two cups of water, we’d count down the twenty minutes until we could pull our snack of cooked fluff off the electric burner. Setting it on the floor in the middle of the kitchen — a dishtowel folded beneath it to keep the rug from melting — we’d add chunks of butter and generous shakes of salt to our work.

Then, leaning our heads over the pot, foreheads knocking, we’d dig our forks into the mounds of white grains, murmuring “Yummmm” to each other until the whole thing was gone.

All they did was take a notion to make a meal together.

What they achieved was so much more.

Leave a Reply