Her eyes filled with tears as I spoke.

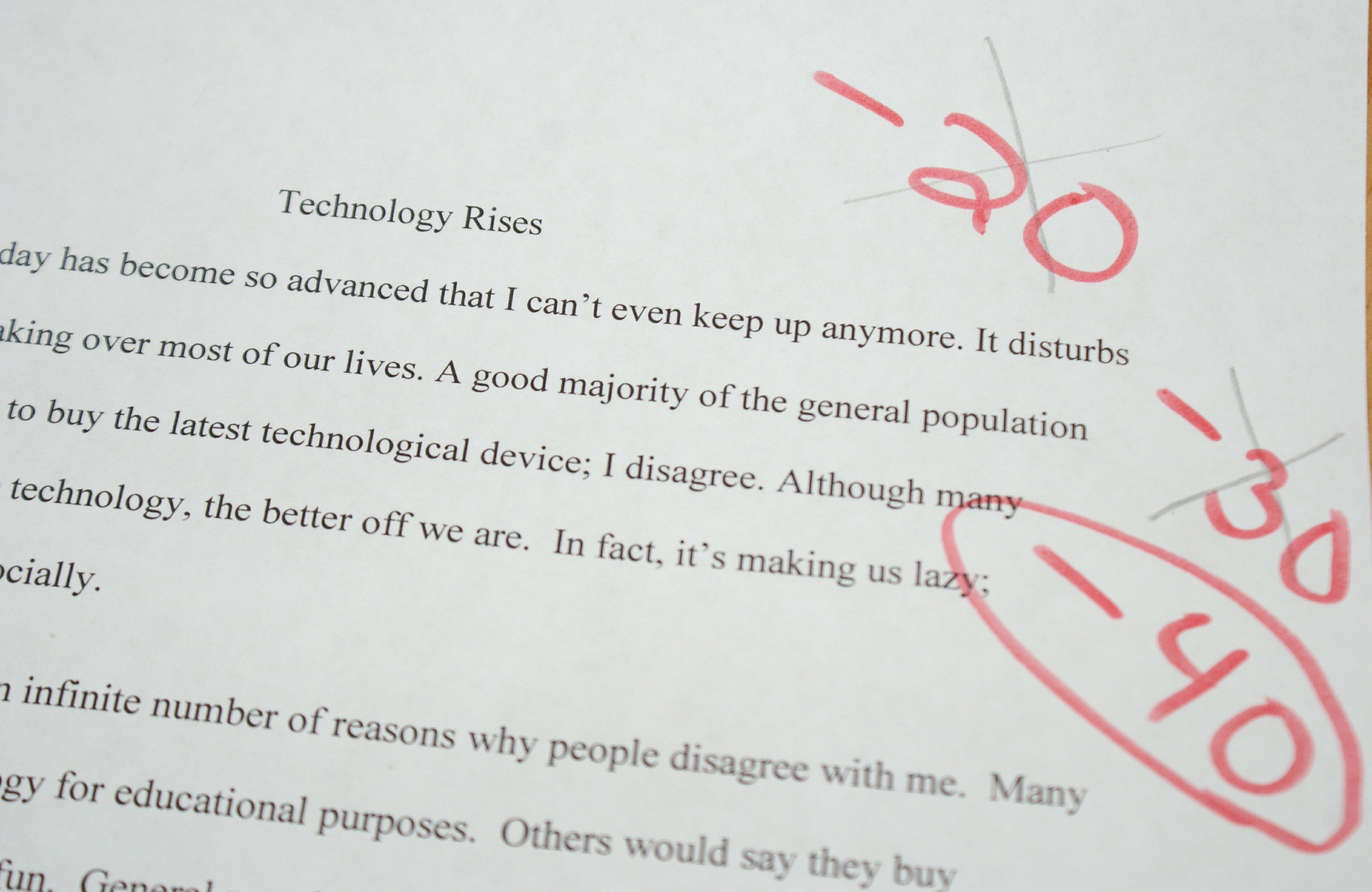

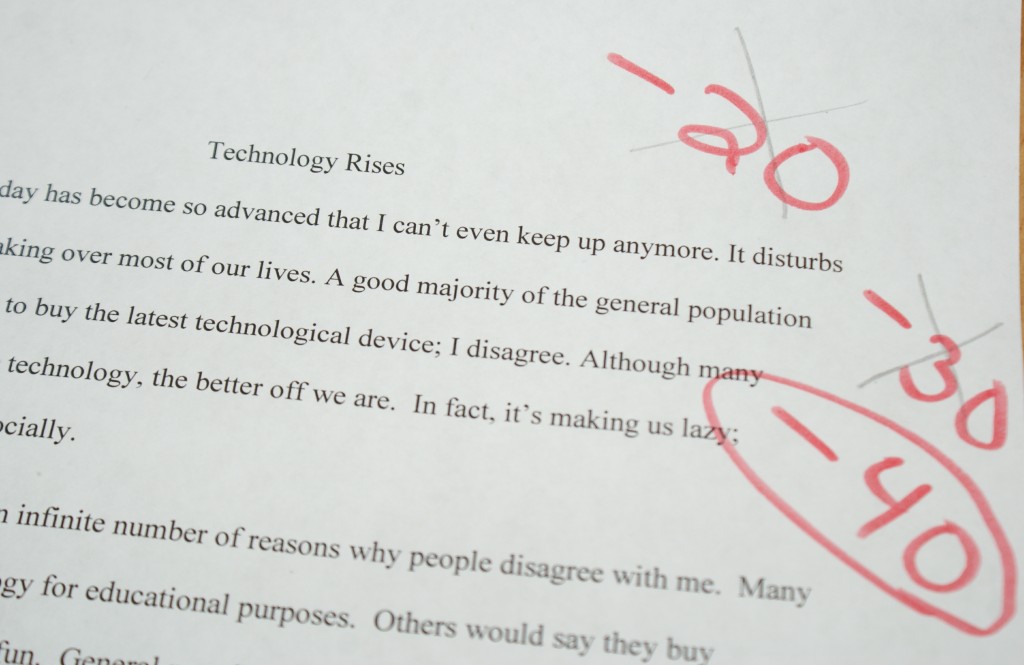

“Yup, you will lose twenty points on your essay if you submit it today. The policy is that you lose ten points for each day that it’s late, and since today is Wednesday, and the paper was due Monday, that’s what you’re dealing with.” I stood in front of her, having fielded her question as I made my way around the classroom during a group activity. Moments before, I had been checking in on everyone’s progress; when I reached her and her partner’s corner of the room, the student had stopped working to ask if she truly had to lose points for turning in her essay past the deadline.

Upon hearing my answer, she slumped down in her chair and leaned her head onto her bent arm, propping her upper body against the wall. Blinking rapidly, trying to get a hold of herself, her speech was agitated. “But I don’t want to lose twenty points. That means I might as well just take a zero–”

“NOOOO, don’t think of it that way,” interrupted her partner, a thirty-six-year-old mother of three. “You have to turn in your paper today. Do it today, right after class, when you go home. You can email it to Jocelyn or put it in the Dropbox online, and you can still get most of the points!”

I agreed with the partner’s advice and emphasized the logical option: “At this point in time, losing twenty points is the best possible deal you can get, so please, please, please salvage what you can, and submit the thing today–tonight, before midnight. Use the Dropbox as soon as you get home, and turn that paper in. Twenty points does some damage, but you can still get a passing grade.”

“But I don’t want a grade that’s twenty points lower than what the paper should get. It’s a really good paper. I don’t want a lower score on it.” Her face was flushing with emotion as she teetered between tears and anger.

When I responded to her, it felt–as it all too often does with teaching adults–like I was counseling one of my children. Actually, I was counseling this adult in a way my children wouldn’t require, for they would have turned their work in on time. But I tried to help her understand I wasn’t going to make an exception to the policy simply because she wanted me to. Trying to inject a supportive tone into my voice, I told her, “The thing is, you can’t go back in time and change your behaviors from two days ago, when you didn’t turn in your paper. All you have is the chance to make the best possible decision you can today, right now, with the reality that’s in front of you.”

To her credit, she was frustrated with the situation, not with me. Reaching her limit, she threw her hands up and announced, “Screw it. I’ll just take a zero.”

“Wait a minute,” I challenged her. “What’s that attitude about? Do you realize you literally just threw your hands up in the air as you dismissed something that’s bothering you? You have to know that if you don’t turn in this paper, even for meager points, you literally cannot pass this class, as all four out-of-class essays have to be submitted, no matter how poor their scores. Submitting them all is a baseline requirement. So why are you rolling over on this? What’s the benefit to having an attitude of all-or-nothing?”

Even more to her credit, she gave a giggle of self-acknowledgment as she confessed, “Because that’s how I’ve always dealt with everything in my life. If I can’t have it all, my way, then screw it; I’m done.” As her memory flicked back through various life events–becoming pregnant in high school, drug addiction, getting kicked out of her dad’s house–she drew in a huge breath. “I was so sure things were going to change now. I just got a new job, so I’m not unemployed any more, and I was going to prove that I could do my new job and not have it hurt my schoolwork…this was going to be the time I didn’t mess up.”

Her helpful partner chimed in again, “So don’t let it. If you take a zero, then you lose. Turn in your paper today, take the hit, and then you’ll prove something to yourself.”

The partner was a qualified counselor. She had been through Stuff. When she was pregnant with her third child, it was her male OB/GYN who told her she had to leave her husband since the husband was a tyrannical addict. Not only did this advice wake her up to the grimness of her life, it also provided her a life-altering epiphany as she realized, “There’s actually only one man I’ve ever known who’s listened to me and asked me questions. It’s probably not a great sign about the state of my existence that the only caring male I’ve ever known–my doctor–is in my life because he’s paid to be here.” After issuing an ultimatum, she ended up kicking her husband out.

Since making that change, life has not been easy. Divorced, she lost the nice house and comfortable lifestyle she’d enjoyed during her marriage and, as a single mother of three, working as a hairdresser at Great Clips, she has raised her children in poverty. On the day that this hard-working student advised her classmate not to give up, her sixteen-year-old daughter had just received yet another ten-day suspension from school; apparently the ten-day suspension the teenager had received a few months before hadn’t had any effect. In explaining the situation with her daughter, my student provided important perspective: “Do those people at the school not know how hard it is to get her there in the first place? And then they keep kicking her out? I mean, it’s killing me, but at least she’s there.”

As I stood and listened, my wander around the classroom paused at these female students’ table, a handful of thoughts zipped through my mind. Long ago, I learned that judgment is never constructive–yet, naturally, it still tried to nudge its way in. I also battled against frustration. Fatigued by 160 students, all of whom were in the middle of something, my most authentic self wanted to shout, “No matter what’s going on in your world, do your work already, and if you don’t do your work, own the consequences.” Simultaneous to pushing back against judgment and frustration, I was also holding defensiveness at bay. Being a policy enforcer requires an emotional separation from the pleading eyes and tragic words; holding the line made me the bad guy, and it’s difficult not to jut the chin self-righteously in that role. And then there was appreciation–affection!–for the single mother of three who used her voice as Peer more effectively than I could use mine as Teacher. When it came to weathering challenging experiences, trusting that education might transform her existence from one of not enough to one of plenty enough, understanding how exhausting it can be to fight to an upright posture after being ground under life’s heel, she provided her stressed-out table mate with an emotional fist bump. Because my life has been very fortunate, I wasn’t speaking to the late-paper student from a place of “Hey, honey, I’ve been there” empathy–nor, it could be argued, should I have been. However, what I knew in the moment was this: we needed the voice of that poverty-stricken hairdresser in the room. Her energetic and informed point of view, dovetailing with my inflexible standard bearing, created something unexpectedly powerful.

Woefully, easy happy endings are the stuff of Disney and the citizens of Jan Karon’s Mitford.

They are much more rare in the community college classroom.

The agitated student whose essay was doomed to lose twenty points was not magically reformed by the words of Teacher and Peer. She did not race home and submit her “really good paper” to the Dropbox before midnight. Possibly, she had to work. Or she had to pick up her two-year-old from the daycare since they had given her notice that leaving her son with them 16 hours per day was too much. Or she smoked a few outside a brick building while laughing with friends. Or she called up her mother and had a fight. Or she lay down on the couch, wanting to put her feet up for a minute, unable to turn in her paper electronically because she couldn’t afford Internet service in her subsidized apartment.

Another day ticked by. No essay.

Then another. Still no essay.

Four days past due, a semi-good paper slammed into the Dropbox, submitted just late enough to convey an attitude of “Here. Take it. And what-EVER about your lateness policy. But give me points. Or don’t. I don’t care. Except please do.”

And so it goes.

Leave a Reply