“You sure eat a lot of fast food.”

Those eight words killed my appetite – punctured my excitement about dashing into the gas station to grab a couple of sliders at the attached White Castle.

Certainly, I knew how he felt. In the many letters and messages we’d exchanged during our courtship, he’d made it clear.

Yet. Those eight words, a casual observation made by the man I had been dating and was beginning to love, shrank me, a 31-year-old woman, into someone jittery, defensive, diminished.

Those eight words sniffed prissily at my history.

***

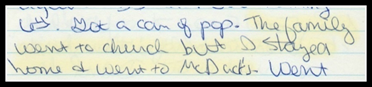

In 1982, for my 15th birthday, my dad gave me a 12-pack of Mello Yello. It was a thoughtful gift, one that indicated he understood the teenager lurking in the basement. To be presented with my own, private 12-pack of pop – something I never had to share with my siblings, something I could hoard in my bedroom closet – was a kind of power.

Dad didn’t use words much, but our shared meals, as recorded in my diary – pages of artless divulgences stashed in the same closet as the Mello-Yello – constituted warm communication.

Sometimes, to cap off a lethargic day, we’d drive in silence to Bonanza, the low-end, Old West-themed chain “steakhouse” where we’d order a prime rib dinner, maybe top sirloin, not for a special occasion but because it was Wednesday, no one wanted to cook, and we had coupons.

After ladling Ranch dressing onto iceberg lettuce at the salad bar and peeling the aluminum foil from baked potatoes, we’d return to our booth and sit in vinyl communion, relishing the paucity of demands on our energy and the fullness of our plates.

***

She spent her youth plucking, pitting, and canning, but my mother never liked to cook. As a woman born in 1935, graduating college in the 1950s, marrying in the early 1960s, her lack of interest in the kitchen smelled of “radical feminist statement.”

She certainly didn’t intend it that way: she just didn’t like to cook.

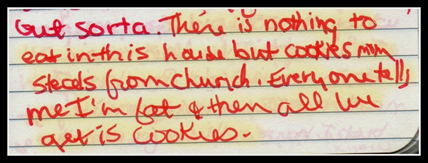

Dutifully, she would make chicken noodle soup, a Sunday roast, “poor man’s” beef stroganoff, chocolate chip cookies. She loved more adventurous foods, but none of us understood the appeal of her mushrooms and asparagus. “More for me!” she’d puff, fishing around the can, trying to spear another limp spear or soppy button.

For my mom, the day-in-day-out call of the kitchen always chafed. Planning a nightly meal became even more thorny when she escaped into full-time work.

***

A crumpled Baby Ruth wrapper in hand, I opened the cabinet below the kitchen sink and dropped it into the trash. Rustling faintly, the wrapper unfurled inside an empty Campbell’s can. So that was the tantalizing smell permeating the house: pork chops slow cooking in Cream of Mushroom soup.

In the ‘80s, although my dad tried to catch up with the times, mastering a few crock pot meals and the occasional batch of chili, willingly scrubbing the pots and pans, his contributions were voluntary. Failure to plan a meal did not tarnish him.

It was my mother who was on the hook for getting food into her kids’ mouths – even when those kids were old enough to pitch in and figure out food for themselves. Yet, like our parents, we couldn’t be bothered to conceive of a plan that would cover the family. My sister and I might share a box of mac ‘n cheese; my brother would fry himself a couple hamburger patties. But tending to the common interest? Flattening ourselves, we refused the challenge.

***

In the early years, our family would head to McDonald’s after church on Sunday – a righteous reward. In our best clothes, we perched on plastic seats, the paper around our hamburgers crackling as we unfolded it. Carefully, I would scrape the rehydrated onions off the patty and offer them to my dad. After tipping our trays into the swinging mouths of the garbage bins, we’d take a minute to embrace the flame-haired Ronald McDonald on a bench outside.

A decade later, a teen trying to separate herself, already disenchanted with the ritual and community of church, I bypassed the worship and went straight to the reward.

***

Desperate to be liked, always desperate to be liked, I spent hours with my face pressed to mirrors – pursuing pimples, applying eye shadow, sucking in my stomach, admiring the star embroidered onto the pocket of my HASH jeans, angling the curling iron. Fancying that effort could result in popularity, I hit the halls of the school hoping that the height of my bangs would distract from the tenderness of my heart.

Too many days, I lay face down on my waterbed, smudging mascara tears into the pillowcase.

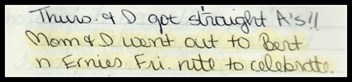

Tests saved me. Essays redeemed me. And when the report card came home – evidence that someone liked me – my mom and I celebrated the results by eating out. A musician, my dad had evening rehearsals. My sister found her place in the world through babysitting most nights. My brother refused to join in, noting that we didn’t have enough money to be eating out.

Saluting my achievement worked for a couple of us. As I plowed my way through a mountain of nachos, my mom sighed about her job as a church secretary. Dabbing at crumbs, she alternated bites of turkey sandwich with tidbits of despair about the pastor’s cruelty. To counterbalance her misery, we ordered the cheesecake.

***

My mother marched to the television and twisted the knob until the screen went dark. “It’s after 9 p.m., it’s a school night, and I don’t think that’s a good show for kids to be watching.”

Lazily, my brother unfolded his height from the plaid couch and skirted our mom’s form, still clad in the belted trench coat she wore to work. Leaning around her, he snapped the television back to life, explaining, “We watch this show every week. It’s called Charlie’s Angels. So what if they’re wearing bikinis. Don’t worry about it.”

Two, three, four, five nights a week, my parents weren’t home. Sometimes they’d swing by the house between work and the choir and handbell rehearsals that were their avocation. Providing music for several churches in town, they would often attend more than one rehearsal in a single evening. My father conducted, and my mother sang. When it came to bells, my mom would conduct, and my dad would ring. Creating music for communities of faith united them.

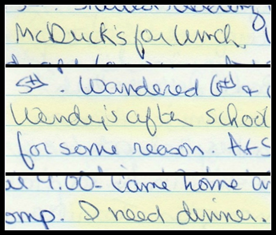

At the same time, we kids would be home, rattling around the kitchen looking for food, often hopping in the car to grab a single, no pickles, no tomato.

I thought I liked the independence.

***

My first car was a Pontiac, a boat of a thing that felt 40-feet long as it swayed across the asphalt. From the day I earned my license – passing the test even though the man scoring it stormed out of the passenger seat after my sixth attempt to parallel park, huffing “I can tell you’re never going to fit into that space!” – I packed the car with friends who, like me, were in search of an invisible something; we called it “fun.” Cruising The Point, hanging out the windows, whipping U-turns, grabbing Whoppers, trying to buy beer, our collective mobility assured us We Had Lives. And if we had lives, We Mattered.

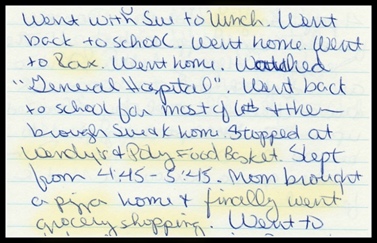

I careened through my teen years, a lack of structure my sole purpose. Attending school, watching soap operas, winging around with friends, trying to fill the belly – the days were a spin of “Go here, go there, go back, go home, go get, find food.”

Direction came only when I turned a slow left towards the pick-up window after yelling at a stranger through an intercom.

***

Home alone on a Sunday morning, planted two feet from the television screen, sitting on the steamer trunk my grandmother had once taken to Europe, I watched State Fair. During the commercials, I raced to the vanity mirror in the bedroom and pulled my nightgown tightly around my hips, measuring my girth, assuring myself the reflection qualified as “hourglass.” Mostly, I was waiting for my mom to get home from the morning’s services. I was hungry.

Much of my parents’ identities was tied up in church. For years, we all attended the Presbyterian church together. Later, our family switched to a Lutheran congregation. A few years after that, my dad moved, seemingly on his own, to a different Lutheran church. Eventually, my mom followed. Collecting churches, they expanded the places where they made music, my mom driving one direction in her car, my dad the other way in his. Occasionally, they’d rendezvous in front of an altar.

By the time I hit fourteen, I knew: when I was sitting in a pew, leafing through the hymnal, sketching out a game of tic-tac-toe on the offering envelope, I floated in a grey limbo, feeding my spirit with something that felt artificial.

Preferring late nights and late mornings, I asserted myself. Outside of holidays, I didn’t want to go to church. This sent a tremor through my parents. Then, shrugging, they focused more hours on ringing and singing.

***

Uneasily, saliva pooling in my mouth, I stood at the Taco Bell counter next to my dad. If I ordered too much, he might comment on my weight. Hoping it made me smaller, I ordered one crunchy taco and a glass of water.

Perched on a hard, plastic seat, I bit through the shell, my teeth sliding easily through the sloppy fillings. The waxy cheese offered no resistance; the meat plopped onto the paper lining my tray. Deliberately, I pinched it, grasping at every possible bite.

Wadding the empty paper into a ball, I admitted, “That was so good. I could eat more of those.”

Dad’s eyebrows lifted; he was pleased by my appreciation of the food he’d provided. Expansively, he offered, “Well, then, let’s get you another one.”

The food waiting for us under warming lamps lubricated our squeaks, spared us from thinking, sidestepped the trick of a family meal. Unquestionably, going out to eat was a marker of celebration, ease, excitement, socializing, connection.

At the same time, without question, all that was going on inside our bodies – compromised nutrition, stuffing the holes with fries, never having a coordinated plan, lacking energy to make the effort, finding ways to never look each other in the eyes – reflected a festering dysfunction.

I thought we were okay. We were not okay.

***

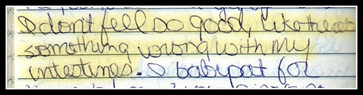

“Bleeeech!” I spit the sour milk into the sink. I’d covered the Cheerios until they floated, priding myself on eating something before a hot fudge sundae at lunchtime, only to discover as spoon hit mouth that the milk had gone off.

When I was 15, my nose for rot was still developing. I’d given the carton a cursory sniff before tipping it into a full-on pour. It wasn’t until the cereal was fully saturated that I realized I was shoveling spoilage into my face.

It would take decades before I could perceive decay with any accuracy; decades before I could realize, with a quick whiff, that the milk in the fridge had expired; decades before I stopped trusting my well-being to artificial preservation; decades before chemical-laden food prepared by indifferent minimum-wage workers stopped being the safe choice.

***

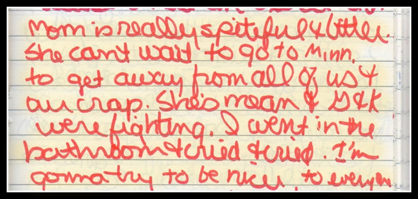

Upstairs, the walls of my sister’s room were painted a sunny yellow; her curtains danced with flowers. The bright décor was deceptive. A more accurate reflection of our collective teenage mood was the basement, where my brother and I lounged in dark wood paneling, tucking our dirty dishes under the plaid couch, occasionally breaking dried clumps of sauce out of the industrial orange carpet.

It was good that my siblings’ bedrooms occupied separate floors, good that we rarely all sat down to a dinner, good to have distance between them. They didn’t much like each other.

Often, my mom ached for distance, too.

In the midst of the unhappiness, I locked the bathroom door and peeled lengths of toilet paper off the roll, mopping at my face. When I was done, I’d hold my hands under the faucet and splash cold water over my blotchy skin, mesmerized by the bubbles sliding down the drain.

***

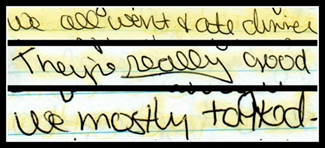

Just before 5 p.m., my dormmates and I would line up outside the locked doors to the cafeteria. Uneasy with each other, strangers still, we’d stick to talk of movies, professors, friends back home. When, at last, the cafeteria doors swung open, our pack would move en masse into the huge, light-filled room, the group splintering as each of us hunted down the answer to a specific hunger.

At eighteen, echoing my mother’s yearnings, I left Montana and headed to Minnesota for college. I got away from it all. I got away from the crap. I was mean and spiteful and bitter, full of tears and a desire to be nicer. To everyone.

A boy named Tim always filled multiple glasses with milk and slathered a raft of peanut butter onto his plate. My roommate could be counted on to reach for the spaghetti while a girl from Wisconsin with an asymmetrical haircut reliably went for blueberry yogurt mixed with Grape Nuts. Most nights, Jeff from Michigan would finish most meals by dunking a tea bag into a mug of hot water. Accustomed to the challenge of figuring out my meals, I appreciated both the predictability and the choice – even though many of the entrees baffled me, stumping my beef-geared tastes. Eventually, I became a devotee of the salad bar, often topping off my meal with a bowl or two of Captain Crunch.

After a few minutes of individual wandering, seeking the security of other bodies, we’d converge at one of the long tables. No one had to spend time cooking chili cheese casserole for the group. None of us had to plan the menu. Unencumbered, we sparked with each other for hours, taking breaks to scoop cones of chocolate peanut butter ice cream, to toast a bagel, to refill a bowl with Lucky Charms, to watch Tim drink three more glasses of milk.

Leaving home offered me a novel experience: a nightly family meal.

***

“We’ll split a bread bowl salad,” my dad told the waitress at Perkins. A whole salad for each of them would have been too much. Plus, one was cheaper than two. When the bowl arrived, my mom scooted closer; her arms could only reach so far.

Alone in the house, the nest empty, my parents attended rehearsals, cast about for dinner, moved to a bigger place. My dad watched Jeopardy in his recliner; my mom crowed about the new bathroom that belonged to her, only her. One time, she put my father through a test without telling him: she refused to speak to him unless he initiated the conversation. They didn’t talk for three months. I doubt he noticed.

***

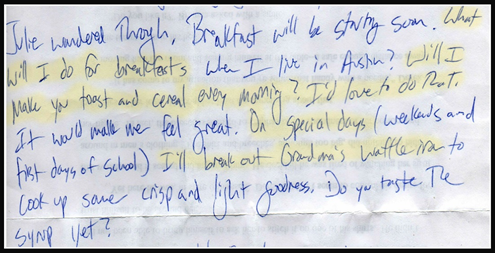

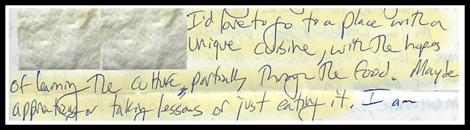

Traveling through Eastern Europe with my sister, flying to Iceland to camp with a friend, I lived for his letters. He’d written them before I left the country, handed over a well-kissed bundle of them, told me to open one each day while I was gone. Every evening, after riding a bus into Romania, marveling at the hard-boiled egg in my Polish borscht, swimming in a warm pool in Akureyri, I capped off the day’s novelty by slitting an envelope and easing his familiar voice out of the folds.

Infatuated, he contemplated the shape of our future. What would our days look like when we were together all the time? How could he be there for me? What would we eat? How would we celebrate life’s joys?

The morning after I returned from my trip, he proposed. A few months later, I married the man who wounded me when he noted that I ate too much fast food. Our years together propelled me into a slow-motion trust fall away from the shaky habits of my youth, urged a blind release into a solid landing. In falling, I discovered asparagus doesn’t come from a can, mushrooms can be transcendent, a wok heaped with bok choy is sizzling beauty.

***

After the birth of our first baby, we left her for a night with my parents. Having smiled at her and tickled her feet, Dad left. Later, without having told us she was already booked, Mom headed to a rehearsal, leaving the toddler with my brother. The next day, not interested in smashing a banana or spreading a handful of cereal onto her high chair tray, my mom and brother took her to McDonald’s, where they were amazed at the enthusiasm the diaper-clad towhead brought to dragging French fries through ketchup. It was amazing: our girl had never eaten processed sugar or deep-fried food before that familial initiation.

***

On the day my father opened the front door, not knowing he was being served, unaware his marriage was ending as it neared the 40-year mark, his eyes filled with an expansive view of the Pryor Mountains, 90 miles away. All he’d ever wanted, outside of a cheap sirloin at Bonanza, was the comfort of a yawning vista.

In the five months between their divorce and my father’s death, Dad spent a short period at an independent living home, a place where men were rare and valued. Surrounded by attentive women, no longer slipping around the edges of unexpressed anger, never having to plan ahead, he looked forward to mealtimes.

For my mom, craving demonstrated affection, the divorce freed her to seek out a new dynamic. Dating around, she moved in with a diabetic who loved Nut Goodies; later, she based a relationship with an unpleasant man on their mutual love of Diet Pepsi, no ice, slice of lemon.

Altogether, she stopped attending church. She was ready to buy her own cookies.

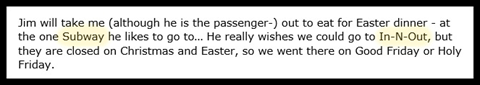

Eventually, Mom remarried. Her new husband, first unwilling and then unable to make himself a sandwich, sits in his chair, baptized by the glow of the television. Together, they watch Jeopardy. Eating out for them is not only a marker of celebration, ease, excitement, socializing, connection. It’s also that no one wants to be in charge of food; again, the responsibility falls to my mother. Fast food is the thing they do together, the reason for him to shower and get dressed. As his memory fades, there are two restaurants he still likes; her messages to us are peppered with the words “In-N-Out” and “Subway.” In this new marriage, life is completely different, yet nothing’s changed.

***

Disoriented by how foreign Turkey felt, our young family clung together. At seven and ten, the kids were still young enough to uproot for the wild hair of a sabbatical year abroad. So there we were: in Cappadocia, pacing our days with the Call to Prayer, wondering how headscarves related to politics. A trip to the hardware store required not only a dictionary but also a deep inhale. Even minor transactions were exhausting.

Then, one evening, at a party of expatriates teeming with wine and shouted introductions, I latched onto a Turkish woman named Eren, a woman who ran her own hotel in the next town, a woman willing to answer my myriad questions about the culture and history of the dusty region we’d decided to call home.

Several days later, Eren sent a car to our 400-year-old stone home. With typical Turkish hospitality, she had offered to give our family a cooking lesson at her hotel. Unused to the idea that a man would be a kitchen devotee, Eren spoke mostly to me, but it was my husband who tracked her instructions closely. I took notes. He asked questions, watched her hands. At the end of three hours, we sat down at a table outside to share the lesson’s yield: dolmas, leeks with carrots, bulgur, kofte, a dip of roasted eggplant.

The meal that afternoon lasted an hour, but the information stuck. Years later, six thousand miles from that hotel kitchen, I come home from a muddy trail run and find him smiling with anticipation as he rotates an eggplant over an open flame.

***

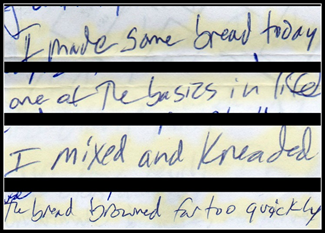

“The closest thing I have to ‘faith’ is the way I feel about yeast.” An agnostic, my husband explores belief in the invisible each Sunday as he punches dough on the counter. His wedding ring rests on the windowsill, a witness, while his capable hands turn and thump the softness, the movements a conjuring. A calibration of heat, time, temperature, his loaves are hope made tangible.

On the radiator, covered by a towel, the dough rises. The kitchen is a mess, a visual cacophony of sticky bowls and wooden spoons. He wipes the counter, but when the moisture dries, chalky streaks smirk. His back-up crew, I wipe the green laminate again, this time with a paper towel; mournfully, I note that even the sides of the counters are coated with floury dust, that a third rubdown is in order. Worriedly, I remark that a drop-in visitor would flinch at the sty that is our kitchen.

“Mess is part of living life. All this flour everywhere means we’re doing it right,” the baker reminds me.

Later that night, when the house is dark and quiet, I stand in the kitchen, slicing a piece – then another – slathering butter, biting into the remnant warmth, feeling the crumbs dissolve on my tongue.

***

Slowly, the boy’s hand reaches towards the tv tray next to his bed. He is searching for relief, for painkillers, gum, something to swallow that will make him feel better.

Our thirteen-year-old just had his tonsils out. Limp, muffled-voiced, he winces with every swallow. Within a day of surgery, he refuses popsicles. They taste “too fake.” Although his stomach is hungry, little sounds appealing.

Except maybe homemade mac ‘n cheese, and if there’s some leftover pho broth in the freezer, he could sip a mug of that. Also, as long as I’m running downstairs, maybe he could tolerate a glass of the hibiscus Agua de Jamaica that Dad brews.

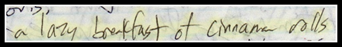

While the boy recovers, our girl is on a high school trip in Europe. In the days before her departure, she stacked clothes in her room, poured shampoo into tiny bottles, practiced using her ATM card. Feeling nostalgic in the fashion of a teenager leaving home for ten days, she requested a special pre-trip treat: Dad’s cinnamon rolls.

It’s beyond the sixteen-year-old’s scope, but sticky rolls are an integral part of her father’s history, something he made for himself when he lived alone, for roommates when he shared spaces, for friends when they helped him move, for his new girlfriend when she drove five hours north to visit. Setting out heaping platters is an extravagant statement of affection from an otherwise quiet man.

***

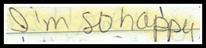

My stomach growls, and I heft ceramic plates out of the cupboard. A mountain of dirty dishes rests next to the sink. Next to the stove, a chopping knife lies atop a cutting board, still littered with stems. The mess can wait.

With the grace of passing years, I have arrived at an essential realization: happiness is authentic when someone’s hands have touched it, pressed a knife blade into the sinew, peeled back the surface, diced, tossed, grated the whole, exposing the hidden facets, baring the delicate subtleties.

Minutes later, I lift the fork to mouth, wrapping my lips around a complex bite. I am eating my husband’s questions about that week’s menu. I am eating the shopping list he made. I am eating his hours at the grocery store. I am eating the chopping he did before work, the frying he did after. I am eating the heat of the oven, our day’s debriefing, the intimate conversation we had while he stirred wooden spoon in skillet. I am eating my husband’s cells, sloughed off from his skin as he worked over our food.

With each rich, thought-filled bite, I am eating clean, healthy love.

Leave a Reply