A couple of nights ago, we sat in a “preparing your child for high school” meeting at the middle school.

Several times, the speaker referred to the date of an open house “which was in the email we sent out last week.”

Leaning towards Byron, I whispered, “Did you see a date in that email?” No, he did not recall seeing a date. “We should stop and tell her on the way out, then, that they didn’t include the date, so they should send out a follow-up email.”

Before we did that, however, Byron whipped out his phone and scrolled through past emails. Ah, the date for the open house HAD been in the original message — in an attachment that neither of us had opened.

***

It seems to peak around the tenth day of class.

I log in, and both the email and the “Ask Jocelyn” folders within my online classes are peppered with messages from students. Although the wording and nuances vary, the essence of each message is the same: “How do I know what I’m supposed to be doing?”

In response, although the wording and nuances vary, the essence of all my replies is the same: “Take a look around the class. Maybe start with the announcement that greets you on the homepage.”

***

In November of 2016, Outside magazine published an article by David Kushner about an American man, Noel Santillan, who decided to take a much-needed vacation in Iceland. After landing at the Keflavik airport at sunrise, he hopped into his rental car, input the address of his hotel in Reykjavik into the car’s GPS system, and began driving the forty kilometers towards the city.

After about an hour, Santillan started to worry; he didn’t see anything that looked like a city. However, he was committed to this adventure, so on he drove, following the directions given to him by the GPS.

By mid-afternoon, jet-lagged, understanding that he was off course — “There was no one else on the road, but at that point there wasn’t much else to do but follow the line on the screen to its mysterious end. ‘I knew I was going to get somewhere,’ he says. ‘I didn’t know where else to go.’” — Santillan pulled over in a small village and walked into a hotel. After he handed the receptionist his reservation, she burst into laughter.

Santillan was standing in a village on the coast of Iceland, 380 kilometers north of Reykjavik.

***

Student:

Good evening, I was just curious as to when you are going to give out information on the topics for the papers.

If it is a choose your own thing, or you assign the topic. That is all.

Me:

Student:

Are we supposed to have done a discussion question prompt this week? Also, would you like us to keep track of the three week rotation, or will you tell us the specific Mondays that we are supposed to post on? Or… I am just thinking… is this on our calendar for the class?

Me:

You are not supposed to have done a discussion prompt for this week. And the three-week rotation is and will be laid out in three places:

1) The Semester Calendar (under Introductory Information on the Content page — I asked everyone to print it or transfer all assignment due dates to whatever calendar system you use)

2) Within my instructions for all the assignments that are on the Content page

3) And each week, on the main course homepage, within my weekly announcement, there will be a listing of what you need to do, along with deadlines. So, for example, you can look at the current announcement (this week’s starts with the eulogy my friend Nina gave at her dad’s funeral and ends with the assignments for the week) to see what all is due by this Sunday night at 10 p.m.

I’m glad you asked; I don’t want you to be confused or uncertain!

***

The 2014 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to three scientists who shed light on human beings’ “internal GPSes” by discovering two new types of cells in the brain: place cells in the hippocampus and grid cells in the entorhinal cortex. Both types of cells contribute to spatial problem solving and recognition — to the creation of cognitive mapping systems.

Basically, the more we move through the world tracking where we are, the better we get at “dead reckoning,” taking sightings, recognizing familiar paths, correcting ourselves when our location doesn’t make logical sense given our understanding of where we are in a larger picture. As David Kushner notes of these scientists, “Their work has profound implications — not only for our understanding of how we orient ourselves but for how our increasing reliance on technology might be undercutting the system we carry around in our heads.”

***

Student:

For each of the free writing exercise that we have to do for each chapter, do we continue to submit these “journals” into the folder called “Reading Journal Annotations?”

Me:

I’m so glad you’re asking! You, in fact, will not be doing each freewriting exercise for each chapter, and you will only be doing journal annotations (mostly to learn that this way of interacting with a text exists and that you might want to use it in the future) next week. So there is only one document you will ever submit to the “Reading Journal Annotations” folder.

If you want a preview of everything you WILL be doing, you can skim the Semester Calendar (or print it and hang it from your ear like a huge earring) and take a gander at everything that will be due, along with the due dates.

Thanks for checking in on this.

***

When we rely on our own brains to navigate, the challenge activates cells to the point of growth. Literally, the size of the brain increases in those who don’t just stick to known routes, in those who memorize new paths and ways of moving throughout space.

According to David Kushner:

University College London neuroscientist Eleanor Maguire has used magnetic resonance imaging to study the brains of London taxi drivers, finding that their hippocampi increased in volume and developed more neuron-dense gray matter as they memorized the layout of the city. Navigate purely by GPS and you’re unlikely to receive any such benefits. In 2007, Veronique Bohbot, a neuroscientist at McGill University and the Douglas Mental Health University Institute, completed a study comparing the brains of spatial navigators, who develop an understanding of the relationships between landmarks, with stimulus-response navigators, who go into a kind of autopilot mode and follow habitual routes or mechanical directions, like those coming from a GPS. Only the spatial navigators showed significant activity in their hippocampi during a navigation exercise that allowed for different orientation strategies. They also had more gray matter in their hippocampi than the stimulus-response navigators, who don’t build cognitive maps.

Put another way: if we push ourselves to decipher unfamiliar landscapes instead of sticking to the known and the easy, we get smarter.

***

Student: While reading the (very interesting) assigned text, I simply wrote notes and annotations on a legal pad. My question is this: in what form should this assignment be typed and submitted? Should I simply type out my notes as I wrote them or should I rearrange them into more coherent sentences and paragraphs with a little more finesse? Thanks!

Me: Probably the easiest way to communicate what I’m looking for would be to direct you to Week Two on the Content page; there you can see an example of this assignment as completed by a student in a previous semester! Also, if you’d like another example, there’s the one I refer to in my instructions on pp. 107-112 in your textbook.

***

Wikipedia has an entry for “Death by GPS,” a phenomenon common enough that the phrase has been coined. Fortunately, more often it’s the case that lost people — individuals with limited experience in creating cognitive maps, whose hippocampi are measurably smaller, who put faith in screens and computerized voices over noting landmarks and sensing their position within a larger context — have near-misses or become the protagonists in sheepishly recounted stories. In the summer of 2016, The Guardian published an article, “Death by GPS: are satnavs changing our brains?”, detailing multiple stories like that of Noel Satillan. There were the Japanese tourists who drove their car into the ocean in Australia; the woman who drove her car into a lake in Bellevue, Washington, because her GPS told her it was a road; the woman who was aiming for Belgium and only realized she was in Croatia when she looked at the language on street signs; the Swedish couple who were certain they’d arrived at the island of Capri but who were, instead, in an industrial town called Carpi, never wondering why they hadn’t crossed a bridge or needed to take a boat to get to the “island.”

***

Student:

I am in the Emu group and I read that there is a three week rotation between: favorite discussion, group discussion, and discussion question posts. But I couldn’t find anything about which weeks I will have to complete which task? Did I just miss or skip over it? Also I was wondering when the presentations are due, I am assuming you will let us know after we have have signed up for a specific book? Sorry to bother you, but please let me know.

Thank you, have a great day!

Me:

I’m glad you’re asking!

If you go to the Content page, you can look under Introductory Information for the Semester Calendar. That document tells you what each Wild Animal group will be doing each week for the entire semester. It’s also laid out, week by week, on the Content page in my instructions there. As well, each week’s announcement on the main homepage will tell you.

As far as presentations go, all the due dates are listed on the Semester Calendar, too, along with being listed in the weekly instructions on the Content page (and they will be in each week’s announcement on the homepage). Your one chance to choose the book you do your presentation on is now — I’m still waiting for a few more volunteers on The Moon Is Low — but after this first book, I’ll be assigning everyone presentation topics on specific books!

Thanks for checking in. In summary: use the documents on the Content page, and read the weekly announcement, and you’ll be golden.

***

In 2003, a heavy fog suddenly descended on Nantucket Sound. Disoriented, hopelessly lost, two young kayakers died. A half mile away, John Huth, having made note of wind and wave directions as he started out that day, was able to paddle his kayak — blindly but correctly — back to shore.

After that day, distraught that he lived while others died, Huth found a kind of therapy in immersing himself in traditional orienteering techniques. Even more, he wrote a book, The Lost Art of Finding Our Way, and began teaching a class on ancient navigational methods, both of which, according to writer David Kushner, make “. . . a powerful case for learning how to get where you need to go simply by paying attention to the environment around you.”

***

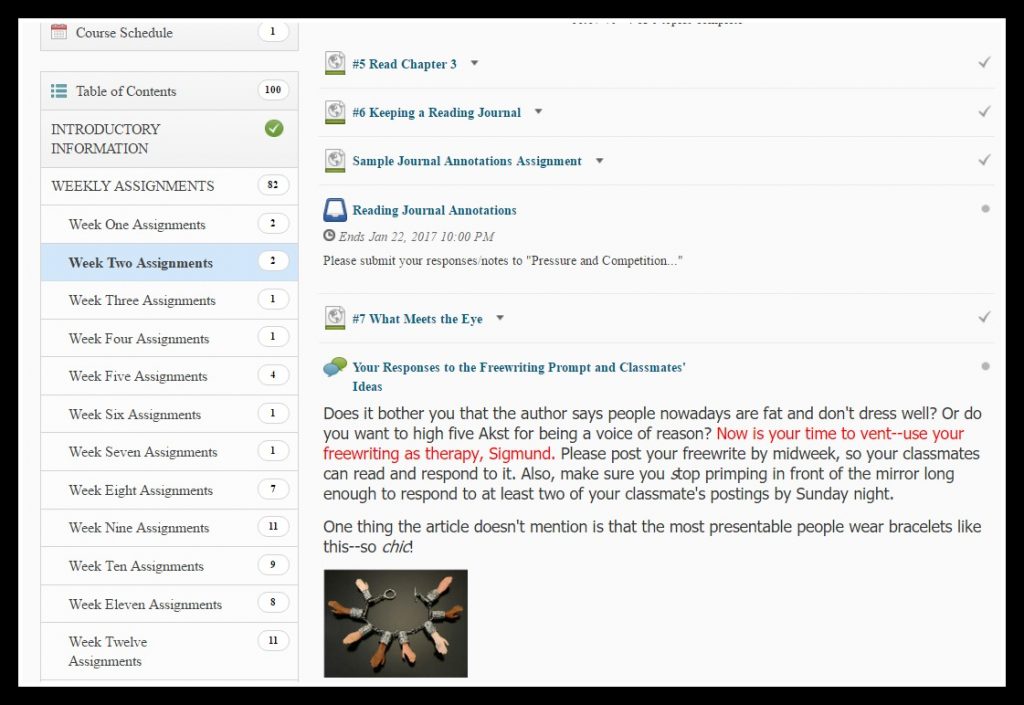

In my online classes, it’s difficult to remain upbeat and patient when I’ve already spent hours creating and posting documents intended to provide clarity. For example, the tenth day of class — when confusion seems at a maximum — occurs during the second week of the semester. And yet from day one, the entire class is there for them, already revealed, completely ready for digestion.

For example, during Week Two the announcement on the homepage says:

So, during the second half of week, please complete Assignments #5-7:

#5–Read Chapter 3 in your Veit and Gould textbook. Savor it. Roll around with all that fun prose.

#6–Read “Pressure and Competition: Academic, Extracurricular, and Parental” (pp. 119-125) and write at least five annotations per the “Keeping a Reading Journal” example on pp. 107-112; your five “reading journal” annotations are due to Assignments by Sunday at 10 p.m.

#7–Participate in the whole-class “What Meets the Eye” (pp. 191-198) discussion; this means you should post your own freewriting and then respond to at least two classmates’ freewritings by Sunday at 10 p.m. I urge you to remember that your posts really need to be well developed and well edited. Put some thought and time into your posts, and make sure you proofread them (no text messaging-type writing, either…please: no LOL usages!).

Supplementally, there is this from the Semester Calendar (which, in case you don’t recall, is under Introductory Information on the Content page. I thought you’d be tracking this shit by now, GENTLE READER):

Week Two–(January 16 through January 22)

Assignments #5-7, explained in greater detail on the Content page

Read Chapter 3, “Strategies for Reading”

Read “Pressure and Competition: Academic, Extracurricular, and Parental” (pp. 119-125) and write at least five annotations per the “Keeping a Reading Journal” example on pp. 107-112; your five “reading journal” annotations are due to Assignments (this was previously called the “Dropbox) by Sunday at 10 p.m.

Read “What Meets the Eye” (pp. 191-198) and freewrite for fifteen minutes in response to the ideas presented in this essay; then participate in the discussion on these essays (post freewriting and responses to classmates by Sunday at 10 p.m.)

And then there’s the listing of the week’s various instructions, also on the Content page. Students can — in a beautiful dream world where whoopee pies are calorie free, tubes of lipstick are tossed to onlookers at parades, and no one ever needs an alarm clock — click on each link and read my detailed instructions for every last individual assignment:

What’s more, in an initial effort to get students to seek out the helpful documents, I have them take a quiz the first week of class in which they answer questions such as, “You will have a big research paper due towards the end of this course. Referring to the Semester Calendar that is located under the heading Introductory Information on the Content page, look for the date when the rough draft of this paper will be due. What date will the rough draft be due?”

Within the landscape of the class, students have been given cues, sign posts, lodestars, street signs, constellations, landmarks. Thus, I feel well justified when I have to inhale slowly…one…two…three…four…lungs are filling on five…six…seven…pushing into eight…nine…TEN…before I reply to each “How do I know what I’m supposed to do?”

It should be easy. They need only take some time to stare at the links on the screen in front of them and then do some clicking and reading.

Everything is there, if only they know how to look.

***

Ancient Norse explorers divided the day into eight sections, each corresponding to a section of the horizon; the spot on the horizon smack in the middle of any of the eight directions was called a daymark (dagmark). In such a way, Scandinavians associated the passing of hours with what they could see in the world around them.

Current online college students are presented with a toolbar across the top of the classroom, a series of five links containing drop-down menus. At eye-line as they sit in front of their computers are these visual “classmarks”: Content, Materials, Communication, Assessments, Resources. The learning curve, for brains used to being told where to go when navigating a new land, requires paying attention to the markers in a way that engages their hippocampi.

Unfortunately, for brains accustomed to instant gratification, navigational confusion is quickly followed by impulse that precludes the engagement of the hippocampus: they send the teacher a message.

***

Mostly, I am able to remain patient with students because I have empathy for their confusion.

Always, I’ve had a terrible sense of direction, have called myself “spatially challenged.” Reliably, when in a new place — heck, when in a place I’ve been many times before — I get lost. To me, GPS, which I rarely have used, is just another method of landing me in Borneo when all I needed was a dozen eggs from the Super One.

Trust: I will NEVER excel at covering the shortest distance between two points.

A fortunate result of a lifetime of being lost is that I’m relatively comfortable with having no idea where I am. Floating randomly around impossible geographies as darkness falls is just another Tuesday to me. Although my hippocampus is undoubtedly smaller than a single tear of panicked desperation, it has grown enough over the decades that I now know to stop myself and take a few seconds of reckoning when I’m running on a new system of trails. Looking at a map before heading out gives me a broad sense of the route, but stopping at every intersection, turning around to see from another perspective what I’ve just passed, and making note of what letter of the alphabet or celebrity face the tree branches resemble has saved me more than once.

***

An article in Directions Magazine explains that landmarks have:

use as organizing features to “anchor” segments of space; use as location identifiers, as to help decide what part of a city or region one is in; and use as choice points, or places where changes in direction are needed when following a route. In the latter cases, on-route landmarks may actually be choice points or may “prime” a decision – such as “turn left after the church.” In an off-route situation, a landmark may provide information about relative location, distance, and direction – as in “if you can see the tower on your left, you’ve made a wrong turn and have gone too far.”

The same article recognizes that some landmarks, the famous ones, are communal while others are person-specific and not necessarily known to others; think “favorite fishing hole” or “the bench where I cried when Idris asked me to move in with him.” This type of landmark is idiosyncratic.

***

I connect with the world through its idiosyncrasies. Many of us do, including people pursuing college degrees.

However, online learning platforms are deliberately free of idiosyncrasy; in the interests of clarity and logic, their design is standardized and uniform — built around communal landmarks. For students whose brains track idiosyncratic landmarks more readily, the class appears devoid of signposts . . . even though there are all those easy links right in front of their eyes, begging for a good clicking, all those laboriously typed instructions from the teacher, begging for a fair reading.

For the brains in the class that nod knowingly when they are told “turn right at the huge rock that looks like Richard Nixon’s profile,” the carefully laid out learning space is a maze where all the walls are white and fifteen feet tall.

It is these students whose messages fill my Inbox. It is these students with whom I remain patient.

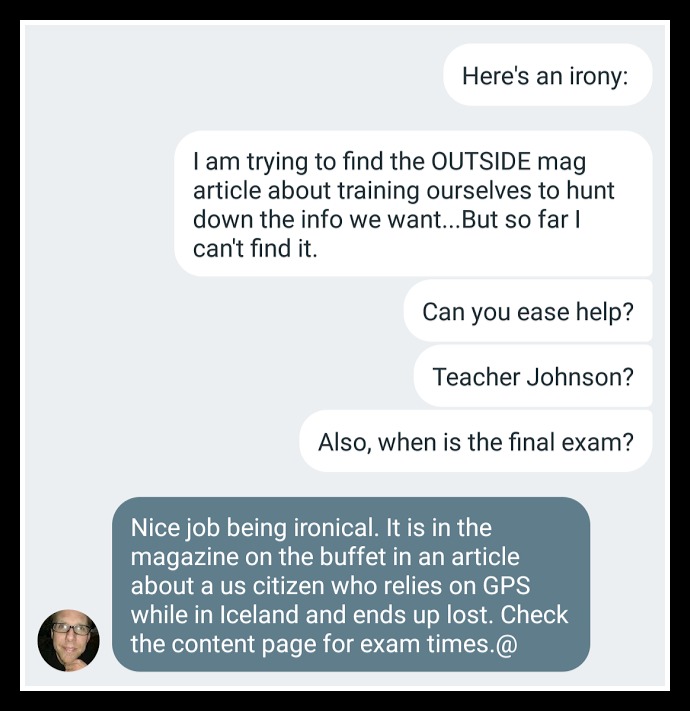

I have to. I’m the person whose husband told her of an article in Outside magazine about how our brains are losing their abilities as “wayfarers” due to technology,

the person who then sat in front of the computer for half an hour the next day, typing in every possible search query,

the person who could not find the article to which her husband had directed her attention,

the person who had to text her husband at work and ask:

***

Now it’s your turn, Gentle Reader:

Where in my online course can you find the Semester Calendar?

_______________________________________________

Leave a Reply