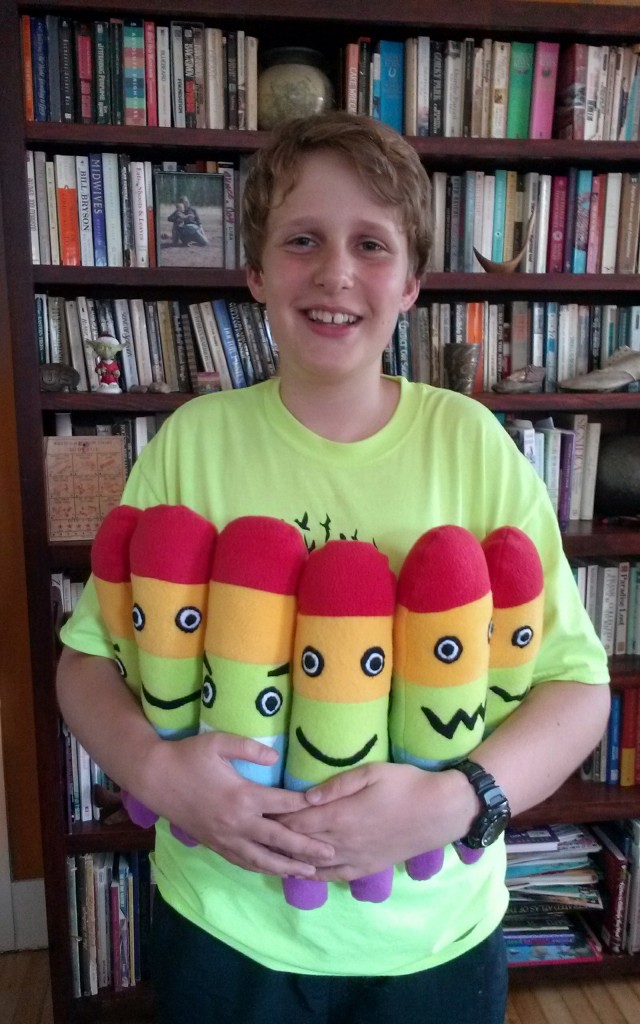

On the twelfth day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: twelve plushies thrumming

——————

We can trace it through the generations: the impulse towards creative expression.

Paco’s paternal grandmother is an artist, a painter.

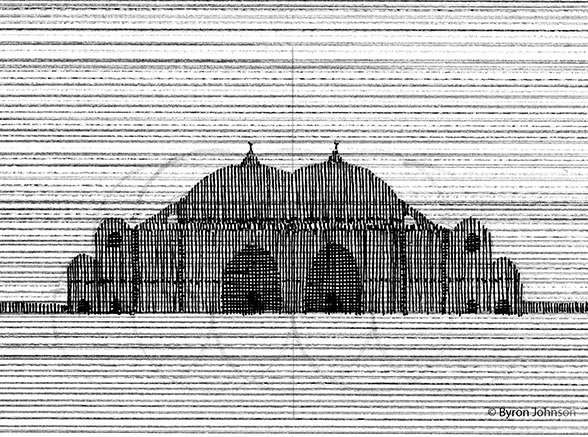

Paco’s paternal grandfather is an architect, a photographer.

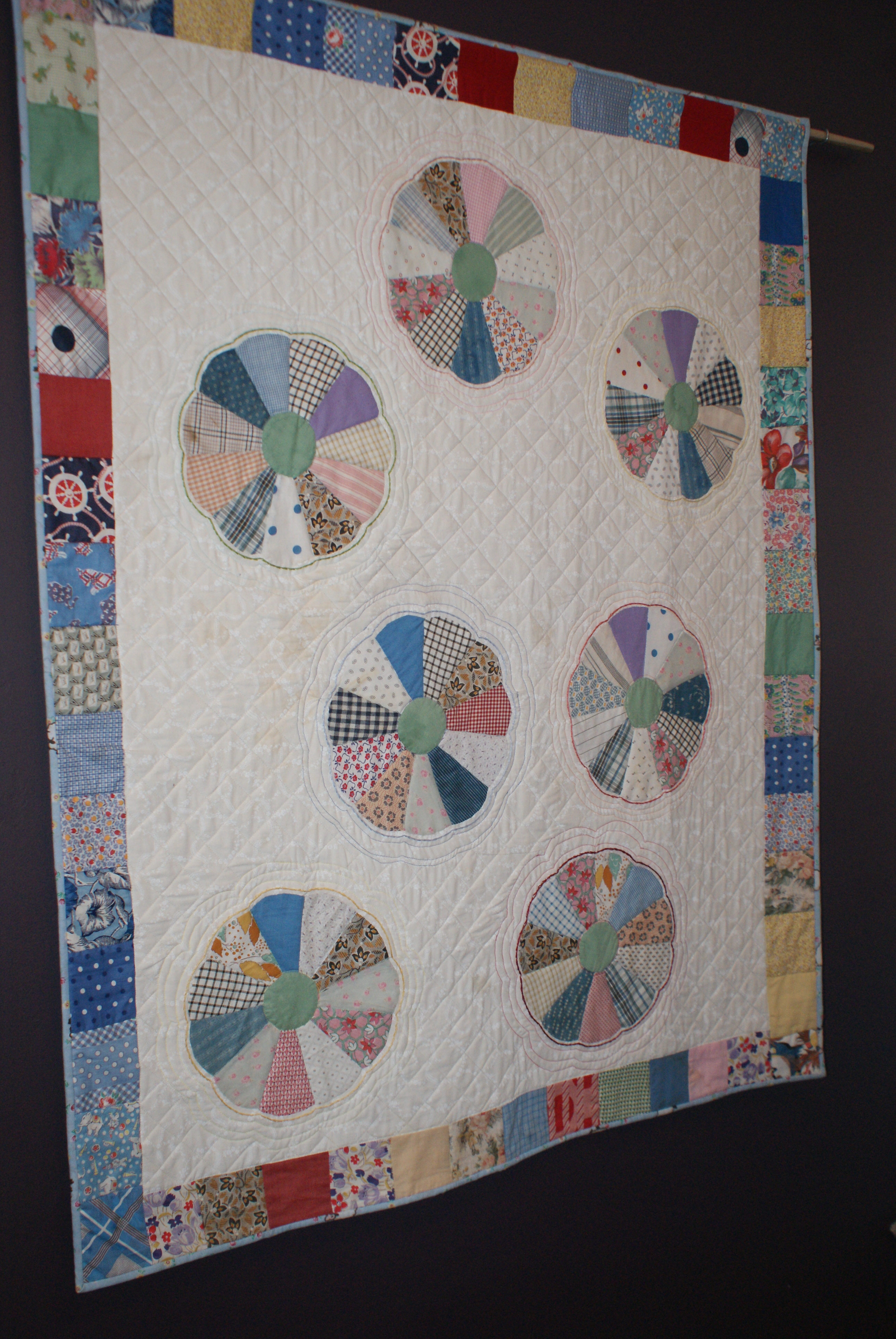

Paco’s maternal grandmother is a hand quilter, a stitcher.

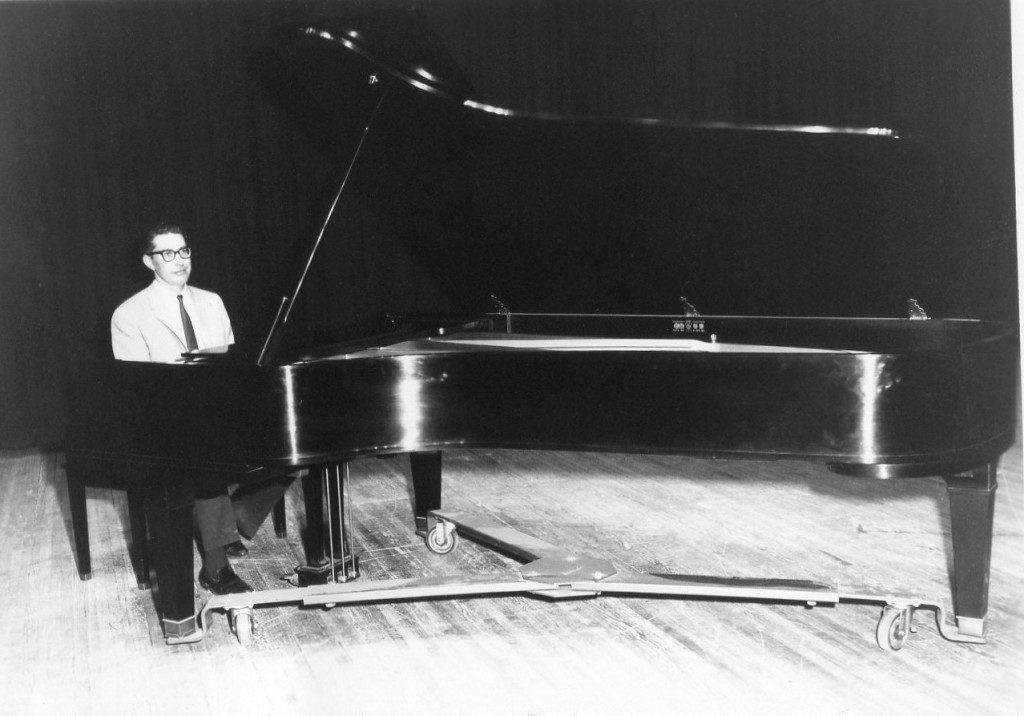

Paco’s maternal grandfather was an opera singer, a tenor.

Hit the play arrow to hear my dad singing in–I’m guessing–the early 1960s, when he was still in his twenties. He started good. He got better.

Paco’s mother exalts in a forceful verb, in a fucking syntactically satisfying expletive. She also posts conversation-provoking images on Instagram. Below, for example, is a commentary on pop culture in which mockable-yet-sympathetic celebrity Khloe Kardashian’s love life is mirrored by a bored Minnesotan in her basement. From this photo, viewers glean how fragile the line is between fame and life below stairs.

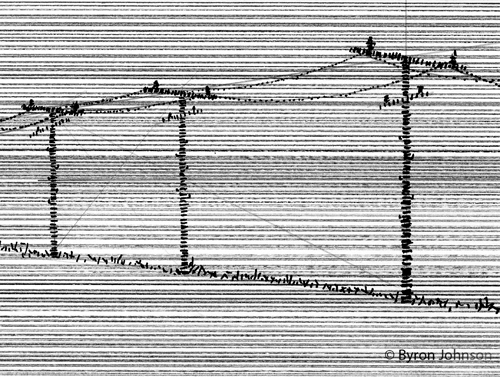

Paco’s father takes black & white, pen & ink, floss & grid, and conjures magic.

All praise to the skies: Paco channels his forebears.

The kid loves him some art. Perks up around some crafts.

As the years pass, and the boy moves from molding Playdough to pounding nails into boards to inking hieroglyphs to drawing monsters to weaving bags, he is wading his way through the possibilities, testing out each form of expression.

Currently, at age twelve, he exhibits a penchant for textiles. Always a tactile person, he falls into the feels of soft, scratchy, raised, fluffy, mesh, hard, ridged. Beyond his love of touch, Paco’s affinity for working with wool and fleece dovetails nicely with his love of video games; this intersection of interests has made him cognizant of art as saleable.

In other words: he has realized that if he makes stuff and sells stuff, he can buy other stuff. Such as video games.

Perhaps this consumeristic attitude coarsens the “art.” On the other hand, the developing sense that “If I create something good, people might buy it” gives us hope that he may one day be able to establish independence. Feed himself. Buy a new pair of Crocs. Purchase a bike, a car, a bus pass. Knit the world’s largest Raggedy Ann doll, sell it to Elon Musk, and take his parents to Fiji.

I mean, seriously. For thousands of years, art has thrived under patronage. If a piece of factory-vomited plastic crap is worth paying for, why not a hand-made, potentially culture-transforming specialty? As I’m sure you ask yourself each night while scrubbing the pots and pans: should not the Countess of Champagne have sponsored the efforts of Chrétien de Troyes?

Much like the bubbly countess, whose coins helped fast-forward the development of the modern novel, I strongly, fervently believe in the financial backing of art.

Indeed, I strongly, fervently believe people should throw five-dollar bills with all the force in their arms at painters, photographers, quilters, singers, hashtagically gifted Instagrammers, and steady-handed pen-and-inkers. More specifically, I strongly, fervently believe people should throw money at my kid if they like the stuff he makes and not only because of Fiji.

This business of patronage is one of the few subjects I can get shouty about, in fact. My Shortlist of Shouty, best read in the voice of my inner Crabby Guy, hollers about a variety of topics:

1) Use the spell and grammar checks provided in your word processing program, but also realize that no computer can replace the human eye–that venerable and vulnerable are not interchangeable;

2) Do not take a sip from my beer when I’m not looking, you greedy snitch;

3) Quit applying nostalgia to the framing of your life story. Of course things were better when you were a kid. YOU WERE A KID;

4) Neighbor, stop unwinding your hose from that creaky rack thing outside the window next to my bed when I’m sleeping;

5) Just say goodbye and walk out the door already instead of dragging out farewells while hairs turn grey. I beseech you: grab your half-empty casserole pan and buzz a straight line to the Subaru while waving over your shoulder;

6) Your nose is not smaller now because you had a deviated septum;

7) Hey, Walmart shoppers, howzabout supporting the arts instead of buying that $7.00 “Hakuna Some Vodka” t-shirt?

To counter the shouty, I have some happy:

Twice a year, our neighbors who run a stained glass studio out of their house hold an art sale. They invite a host of fellow artists to set up tables and displays to sell their wares, as well–so their entire house is populated with pottery, jewelry, paintings, and, yes, my husband’s pen-and-ink drawings

A year and a half ago, Paco asked if he could sit with Byron during the sale to try to move some of his own work. He had his eyes on the new Mario SmashBros game, you see. His parents make him financially responsible for supporting his habit, you see.

As is the way with artistic types, everyone cooed at the notion of a fluffy-headed ten-year-old bringing his products to the sale. At that point, the kid was into felting, both wet and needle. He’d made a bunch of felted balls and tubes, much to the delight of the textile artist ladies at the show. By 5 p.m., they’d informally apprenticed him into their guild.

As the texty-ladies approached him, hoping to clutch him unto their softly clad bosoms, the poor lad was compelled to back away, seeking a corner safe from embrace. He nearly backed into a six-foot custom-ordered stained-glass piece featuring a black bear snagging a fish from a river.

Art gets wildly dangerous when soft bosoms threaten.

That day, hanging out with Dad, eluding the loving ladies, Paco made almost $60. Even better, he’d had a grand time explaining his process to every kind customer who stopped by the table.

That day whet his appetite for the life-improving benefits of the arts.

That day, he went to Target and bought Mario SmashBros.

Thusly, an artist was born.

Currently, driven by a desire to purchase a few old-school Nintendo 64 games, Paco is eyeballing this summer’s upcoming art sale and honing this year’s craft of choice: the rainbow plushie. For months, our dining room table has supported the plushie factory, from fleece to felt to sewing machine to thread.

For long stretches since its inception, the plushie factory has gone unstaffed, perhaps anticipating a boatload of nimble-fingered refugee children washing upon Duluth’s shores, looking for work.

But then, other times, Paco gets in the rainbow mood. It helps when Dad is home and has time to sew, too. It helps when he’s allowed to listen to his Nintendo-related podcasts as he sews. It helps when he wears his fluffy bathrobe when he sews. It helps if he has a comforting latte served in his special New Mexico mug as he sews.

It helps when my mom, the stitcher, comes to visit for a week and is happy to act as a refugee child in his sweatshop.

Now, a week before the art show, Paco is the overseer of a solid rainbow plushie inventory.

It is this mother’s prayer that heaps of crunchy progressive types, preferably towing small children in possession of whiny voices, decide to attend the art show ‘CAUSE PACO’S GOT AN OLD-SCHOOL NINTENDO 64 CONSOLE FOR WHICH HE ONLY OWNS TWO GAMES.

It will be all the better if his customers stop to chat for a minute as they make a purchase, for they will be immediately disarmed by the artist’s disclosure of “I just really like to whipstitch. And at first I hated doing the three layers of the eyes and asked my mom and dad and grandma to do those, but then, on occasion, I really got into it. To be honest, though, I was usually tired before I got to adding the top eye tier, so sometimes I would take off a day or two just for jumping on the trampoline or hanging out on my swing before I felt restored enough to once again face the pupils.”

So maybe he’ll sell some stuff. For sure, he’ll provide gentle, detailed explanations to satisfy every customer’s queries.

More importantly, whenever he sits down to face the dreaded pupils, whenever he lays out fabric in a pleasing design, whenever he talks to interested faces about the decisions he made during the process, he’s further establishing a fundamental relationship in his life: with art–that hobby, that vocation, that passion, that outlet. Whatever role they end up playing in his days, Paco’s expressions of creativity will provide him with companionship.

That’s what art does for the artist. It fills an empty room with promise, staving off loneliness, providing a framework wherein the empty room is the best kind of room. In an empty room, the artist has the space to focus, to take the necessary hours to dab, wipe, type, delete.

Art provides the artist with a singular intimacy, one that cannot be replicated anywhere else in life. What happens between me and an empty page, between my husband and Aida cloth, between my father-in-law and his camera, between my mother-in-law and a blank canvas, between my mom and a stack of cotton squares, between my dad and a score–this thing is unique. I have no human friendship or conversation that approximates the experience of lining up words, hating them, lining up new words, rearranging them, lining up more words, squinting at them, reading them aloud, worrying they make no sense, editing the rhythm, lining up a few more commas, mining my memory, fabricating some details, and finally deciding that if I like it, then someone else might, too, while also acknowledging that if no one else likes it, it’s still good because it did something for me.

Me, alone, energized by my great companion–the stories–is also me having a delightful wrestle with one of my best friends.

The artist takes an idea, goes deep with it, surfaces for gulps of air. All around him, the world carries on, oblivious, paying bills and sweeping the kitchen floor. Committed, propelled by desire to see the full realization of the idea, the artist descends again, sometimes feeling his way, sometimes borne by bliss, sometimes hammering his head. There is no one who understands that something huge is going on except the artist, spinning around inside his idea.

I want this relationship, this intimacy, this companionship for Paco. For the rest of his life, no matter where he lives or what challenges he faces, I want art to be there for him so that he is never alone.

Every sign has it that this will happen. He has the wiring. He has the noise inside of him that craves external shape.

For now, all that is certain is that he likes to whipstitch. He’s thinking he might like to try cross-stitching, like Dad, except instead of gridding out self-portraits, he’ll make some “sprites” from his favorite video games. Also, he really enjoys crumpling tinfoil. And blacksmithing. And toasting almonds.

The impulses are there; the myriad possibilities bash about like choppy waves on a windy Lake Superior. Fortunately, art allows for everything. He can come to it when he needs it. He can forge a toasted almond into a sheath of tinfoil. He can set the terms of that relationship.

He has the rest of his life for art, not merely this one summer when he is twelve, the summer that is fading into a puff of exhaled air.

Indeed, at the end of the summer art sale–at the end of the summer–our leisurely days of together time will draw to a close. We’ll get back on the school-year schedule, and our hours together will be more fragmented. I will be with him every day, yet I will miss him.

However, in the depths of winter, when ice coats the sidewalks and the holidays approach, I will hum a familiar tune to myself and remember that

on the first day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: help at the library

on the second day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: commentary on two purple gloves

on the third day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: three hikes through glens

on the fourth day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: four flaming worksheets containing words

on the fifth day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: fiiiiive bike bell dings

0n the sixth day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: respite from my complaining

0n the seventh day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: seven(teen) birdies a-falling

0n the eighth day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: eight dropped balls a’rolling

on the ninth day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: nine sheep a’leaping

on the tenth day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: ten meringues a’melting

on the eleventh day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: eleven piped positives

and

on the twelfth day of Summer(mas), my middle schooler gave to me: twelve plushies thrumming

Here’s the thing, though:

Despite all his the delight he brings and the mythology I can create around him, he is, at the end of it all, just a boy–just a kid in the midst of becoming who he’ll be.

He’s simply a kid, like any other, special only to those of us who adore him: his grandmother, the painter; his grandfather, the photographer; his other grandmother, the quilter; his mother, who rubs his scalp as they watch Iron Chef America and writes about it later; his father, the master of black-and-white. My father, who will never sing to him.

At the end of it all, he’s just a kid.

I was reminded of this when he provided me with a myth-deflating yelp of laughter one afternoon after he’d been working on a plushie at the dining room table. During his romp in the pile of fabric, he had co-opted a long, skinny remnant of fleece and decided, from that point on, to wear it as a ninja/martial artist headband.

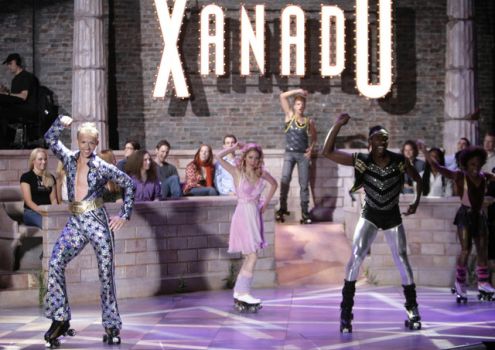

Every time he would tie that long strip of red fabric around his head, he looked, to me, like an extra in

Because Paco’s twelve, because he’s about to start seventh grade, because hormones that haven’t yet landed are still swirling around him, he cultivates reflections of himself, but in odd moments.

Like with a ninja/martial artist headband.

One day after he latched onto that hunk of fleece, he stood in the kitchen, monologuing about throwing stars and nunchucks as he tied the fabric around his head.

Then, wanting to check it out, he wandered into the bathroom and took a look in the mirror. When he came out, his smile spanned the softness of his cheeks. He couldn’t help himself.

Happily, like the unencumbered innocent he still is, he announced:

“Mom, whenever I wear this, my hair looks amazing.”

Leave a Reply