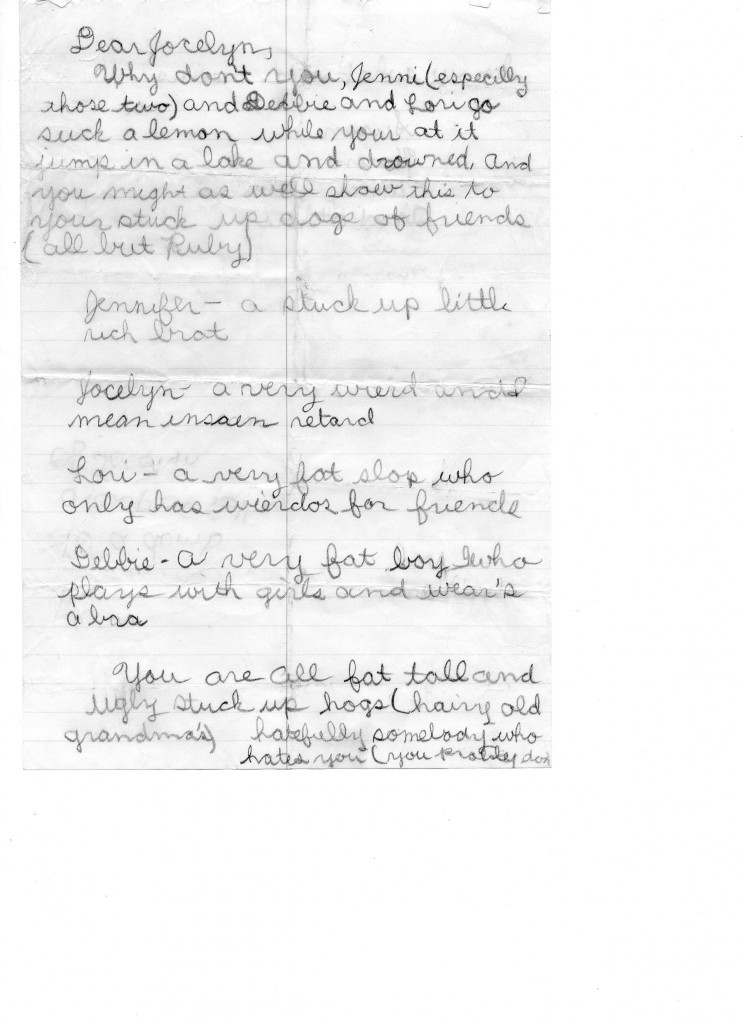

A group of girls–some of them my “best friends”–wrote this note and gave it to me in junior high.

As much as the words still make my stomach hurt (do we ever lose touch with our 11-year-old selves?), and as much as I fall to my knees and thank the sky gods for the fact that my middle school daughter’s life, according to all observations and firsthand reports, is free of this kind of venom, I can also concede that this note is, in its way, normal. I’m not the only one who went through junior high and was the recipient of this kind of Girl Group Mass Attack. The term for this kind of stuff, incidentally, is relational aggression.

I tend to prefer the term soul-shredding bullying, but that’s just a matter of personal preference.

What’s amazing to me, as I consider the contents of this note, is that I can recall incidents of girl-on-girl cruelty in later years that were actually worse—and it’s a sad story, indeed, when junior high isn’t the peak of immature, uninformed judgment. At least the above summary of my flaws and deficiencies addresses the whole person. Not only was I a fat, tall, ugly, hoggish hairy old grandma, the authors of the missive also took into account my weirdness, meanness, insanity, and retardedness—spooning a healthy dollop of “stuck up” on top of it all. I give them credit because they really were considering the entire package and not basing their assessment sheerly on the superficialities of appearance. Had we taken the note into a courtroom, I daresay the accusers could have drummed up significant evidence to prove their claims about my weird, mean, stuck-up insanity. The word “retarded” is loaded with enough complexity, however, that I am certain I could have successfully counterargued that point.

Eventually, after a flurry of notes and tense exchanges, we all reached a kind of détente and were able to move into sixth period, and seventh grade, as “friends.” The arc of decades since the early 1980s has tacked on a few interesting codas: Jennifer, the “stuck up little rich brat,” has become a Lutheran pastor and adopted a daughter from China; Lori, the “very weird fat slop [sic],” still lives in our hometown, has never married, and appears, from a quick Facebook stalking, to take great pride in her motorcycle; Debbie, the “very fat boy who plays with girls and wear’s [sic] a bra,” appears to live in our hometown and work at a local college; of the accusers, two of them are my friends on Facebook and have become teachers (and in a terrible irony, the head note-writer did almost “drowned” in a lake) while the third married a boy from up the street, became a doctor, and moved to Switzerland. In addition to the three who signed their names to the grievance against me, Jenni, Lori, and Debbie, there was also a nebulous “bunch of others” affixed as a final signature. It’s hard to gauge how Bunch of Others is doing 35 years after Notegate, but I feel confident that at least a couple of them now fill their days with full-time Internet trolling and flaming (“u seem to be confusing education and intelligence. you cant even hold to an argment with out going off track and your basic ten year old math is still f***ing stupid to apply too this situation you fat headed little clown. btw your name is clown from now on ok clown?“).

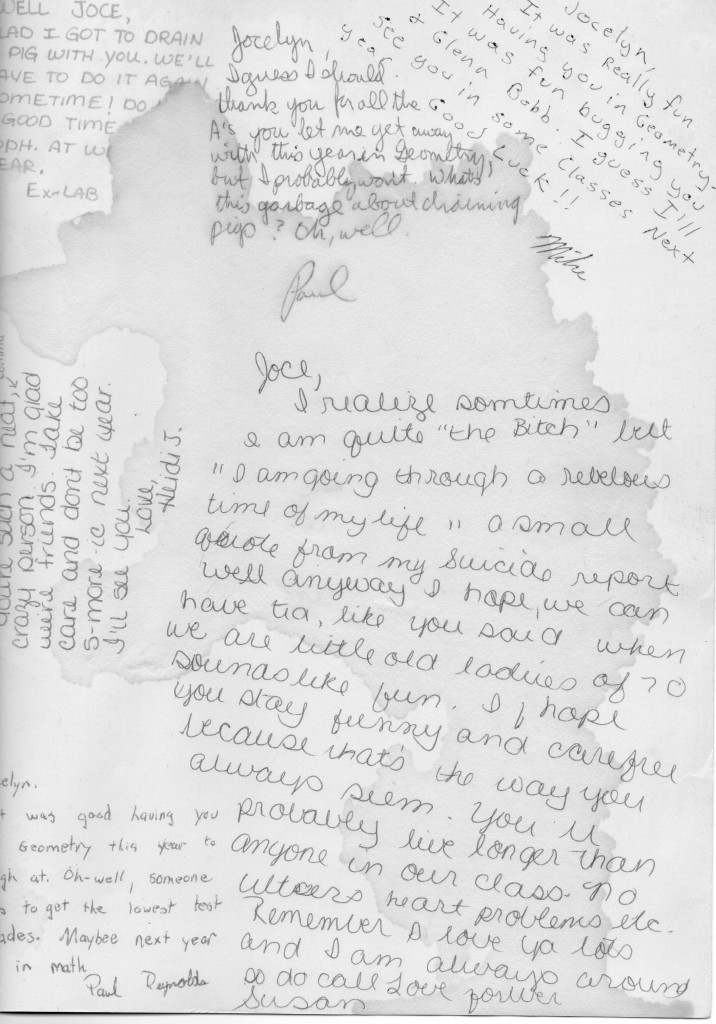

As it does, life, with all its relational ups and downs, carried on—and although I didn’t have the tools yet to understand that cruelty and anger are offshoots of pain, and I didn’t really comprehend that the target of vitriol isn’t actually the source of the problem but, rather, a convenient repository for the attacker’s issues, I look back now on the artifacts from those years and see it all plainly. Just look at the interplay of agony and affection, for example, in a yearbook message the head note-writer later penned:

Because I was young and in the midst of figuring things out, though, the lessons I took from Girl Attacks weren’t ones of compassion or empathy. Instead, what came out of Girl Attacks were strategies of coping and defending, and I’m here to tell you that coping and defending is exhausting work.

I suppose that’s why heading off to college seven years later felt like a most-welcome liberation. Not only did college present a chance to be new again, it also released me from all the various friendship contracts and treaties that had been drawn up over those early years of drunken nights at the drive-in, stolen boyfriends, changes of zip code, and divergently trending report cards.

It’s not that the first weeks of college were easy. Oh, no. Often, I felt lonely and unsure of how to make connections. I would leave my history class, during which the professor had spent more than a few minutes predicting the ways our collective idiocy would play out over the term, and then head to the student union to check my mailbox (empty, unless my mom had written to tell me about symphony concerts or my grandma had penned a note with details about the first frost of the year). After that, I needed to…well, I didn’t know what I was supposed to do to get through those late-afternoon hours. My Indian tapestry and Paul Klee print were already hung on my dorm room wall, and there were only so many times I could play my Howard Jones cassette tape (a super cool girl from Boulder who lived down the hall had this new thing called a “CD player,” but I was still rocking my boom box) while tamping down the urge to sing along loudly “What is loooooooooove, anyway? Does anybody love anybody anyway?” I knew I couldn’t break into boisterous song and the usual maze of accompanying dance steps in the presence of my college peers, these strangers, lest they witness the weird insanity that could be mistaken for retardedness.

Naturally, I had to watch my behavior in that carefully decorated dorm room, as my roommate and I were still figuring each other out. She seemed nice enough, and the fact that she’d brought her hot-air popcorn popper from home opened quite a few doors in JocelynLand. Initially, we worked diligently at Becoming Friends and Facing This New World Together. We’d pop some corn, melting butter in the little “dish” on top, and we’d sit on the grungy carpet and lean against the cinder block walls of our shared room, comparing life stories. As I say, she was plenty nice. And, well, popcorn popper.

There was, however, a kind of reserve in her that kept me from unleashing all my very best weird insanities. She was a petite, gentle, quiet girl. She was extremely pretty. She also had to be smart, or she wouldn’t have been there. She took her classwork seriously.

Unfortunately, she took her lip gloss even more seriously.

What’s more, she was tidy, proper, the kind of 18-year-old who kept her shampoo and conditioner in a basket with a handle and who wore her robe tightly belted on her way to and from the shower. Me? I’d slop across the hall to the bathroom in a big t-shirt and some sweats, juggling handfuls of hygiene products haphazardly. I didn’t plan out my outfits or sit up straight at my desk when I studied or go to bed at 10:30 p.m. When, one night, a random guy from the other end of the floor offered us some ramen noodles that he’d made in his hotpot, she quickly said, “No, thank you. I’m fine” at the same time that I bellowed, “WHAT ARE THESE RAMEN NOODLES OF WHICH YOU SPEAK? WE DO NOT HAVE THEM IN THE LAND FROM WHENCE I COME. Give them to me now, and then give me more!”

Neither of us was doing anything wrong. We were just…different.

Different was okay, if not particularly relaxing or fun.

Then, a few weeks in to fall term, my roommate invited me to come for a walk downtown with a group of freshmen girls from across campus. She’d been hanging out with them a bit and seemed, in her understated way, to be excited about them, especially because they lived in a “cool” dorm. They knew guys who were athletes. Something about the promise of these girls set her former-high-school cheerleader self to thrumming. The plan for the afternoon was to wander through the stores on the main street, maybe get something to eat, and just enjoy an off-campus afternoon of hanging out. Pleased by the invitation and the possibility of new friendship (and perhaps a stop somewhere for popcorn), I tucked in beside my roommate as we headed out to meet the group across campus.

Then.

The whole thing made me sad.

No one was unfriendly. No one was unkind. Everyone handled the pleasantries acceptably.

But no one was actively friendly. No one was clearly kind. No one was interested in talking to me beyond the pleasantries.

To put a finer point on it, no one was interested in me. They were interested in each other and the magical synergy that came from Them as a Collective of Tiny Cutenesses. No one seemed to think my ham-fisted jokes about mannequins in shop windows (“Good thing she’s got a lot of personality ‘cause she sure doesn’t have a head on her shoulders!”) added to the group’s magic.

At some point, maybe a half hour in, I stopped trying, stopped attempting to edge up to the two walking shoulder-to-shoulder in front of me, stopped attempting to compare classes, stopped asking questions about where they’d come from. Even the warm, slanting sun of September couldn’t keep me from being frozen out. At least in junior high, when I was ostracized, the other girls saw me, acknowledged my existence, and then rejected it. Being ostracized through pure indifference was new to me; particularly galling was that, before receiving this version of “go suck a lemon,” I had taken out loans and driven a thousand miles.

Eventually, we all meandered back to campus, them full of the delight of burgeoning friendship, me empty and subdued. At dinnertime, I hardly had the energy to add milk to my second bowl of Captain Crunch.

That night, back in our room, I decided to tell my roommate how the afternoon had felt to me. At least honesty would give us a way to connect to each other with some meaning.

When I told her how left out I’d felt and how I couldn’t understand why no one wanted to walk with me or talk to me, a look of confidence, even wisdom, hit her face. It was as though she knew something I didn’t; she was going to explain, and that would help me.

“The thing is, you have to look like a model in order for these people to like you.”

Well, now. Huh.

Implicit in her explanation was the idea that I had, by being me, disappointed her. She had a vision of her college friends, and if my galumphing self was loitering on the sideline of that imagined 4×6” photo, she would need to pick up her scissors and trim me out.

When my roommate said those words and attempted to convey (her) reality to me, I had a moment.

All the years leading up to college had sent a similar message—that looks equaled character, that looks brought power, that looks should, naturally, reap rewards. Of course good looking kids were the popular ones. Of course good looking kids should be aped and admired. Of course, it was considered a “win” if a good-looking teenager liked me; that friendship made me feel worthy…of something.

By the age of 18, I hadn’t parsed out what all this admiration of pretty people truly meant. All I knew is that the world kept telling me it was better to be pretty because that meant you were better.

Yet.

Everything that had brought me attention and acclaim was distinct from appearance. I did pretty well at playing musical instruments. I had good ideas. I could relate to a variety of types of people. I could memorize a speech and present it to strangers. I was easy at experiencing and sharing laughter. I had an intelligence suited to traditional education. I tested well. I was game for adventure.

On one hand, receiving praise for these gifts was lovely. On the other hand, receiving praise for things Not About Looks, when clearly good looks were the ultimate goal, was devastating, a donkey kick to the gut. Somewhat grimly, I continued to curl my hair each day, at the same time nurturing a little tendril of hope that somewhere an alternate view of success existed.

That’s where the promise of college revealed itself: by heading away from my hometown to a place where the criteria for being part of the club were entirely intelligence-based, I was stepping into a new life, one where the things I was good at were the things that were valued. College was going to redefine the terms of “winning.”

Yet now college was shaping up to be a continuation of the same, tired game.

In junior high, I bought into the game of cruelty; irrationally, my heart, head, and stomach believed that the observations made by The Note Writers had some merit, that they might actually be seeing me really clearly. From those early periods of conflict, I learned skills of coping and defending. By age 18, I was ready to find a less-enervating strategy. I was ready to challenge my heart, head, and stomach to try out moxie rather than capitulation.

I was ready to reject the basic premise.

I was ready to disengage from the dialogue.

I was ready to be done.

And there it was: a glorious moment of clarity. I let my roommate’s sentence work its way through my mind. “The thing is, you have to look like a model in order for these people to like you.” It was more ignorant than the junior high note, in truth, because it set up Winning Life as nothing more than a struggle to be physically attractive.

This–“The thing is, you have to look like a model in order for these people to like you”—was completely one dimensional.

Fortunately, I knew, at age 18, that I was multi-dimensional, what with being weird, stuck up, insane, mean—and perhaps more importantly, I was kind; I made the people around me feel good; I asked smart questions and listened to the answers; I was an expert at peeing in the woods; I was a brain trust of “Facts of Life” trivia.

And, yes, my nose was prominent enough to become a topic of some people’s conversation. My mid-section tended towards sofa-like softness. My breasts were far from pert.

If face and body were the criteria for success with my roommate and her new pack of friends, then I could only fail with them.

As it turned out, I wasn’t ready to begin college as a failure. I thought about it again: “The thing is, you have to look like a model in order for these people to like you.”

The thing is, no, I didn’t.

The upside to that sad afternoon and startling evening conversation was that these events released my roommate and me from trying to create something artificial with each other.

As the term continued, she deepened her friendships with the Beautiful People, and I deepened my friendships with the crew who lived in my dorm.

Just before winter break, my roommate told me she planned to move out—as there was an opening across campus, in the dorm where the cool people lived. I wanted to swoop the back of my hand across my forehead and shout “WHEW!” but instead I remained impassive and said that seemed like a good decision for her.

Then she left for the library

and I ran, my big nose, belly, and breasts in balance with each other, down to the other end of the floor I lived on.

I had news. There was someone I had to find. I needed to tell her—

I needed to tell her that she could move in with me, that we could blast The Pretenders before dinner, that we could sing along loudly with Alison Moyet (“Midddddnight…it’s rainin’ outside…he must be soakin’ wet”), that we could make up nicknames for every third person we saw, that we could dance until 2 a.m., that we could stagger down the main street of the town, holding hands and laughing—

I needed to find the new great friend who had confirmed for me that college was, indeed, going to be a whole new world—

she had asymmetrical hair (weird!), the sharpest wit I’d ever met (mean!), had dated a guy with blue hair in high school (insane!)—

she was so flawed as to be beautifully perfect.*

———————————————

As time passed at college, I would occasionally encounter my former roommate. We would exchange all the acceptable pleasantries without being interested in each other. Even more interestingly, two of the girls who had been part of the pack that day downtown ended up being not at all what they had seemed. Over time, they and I became part of the same large swirl of pals. Now, decades later, one of them has been through the wringer, and the other is a yoga teacher (not a scary one) and a highlight of my Facebook life.

The afternoon when I felt they were ignoring me was, for them, a time when they were excited to get to know each other better. They were just into each other. It had nothing to do with me, and the furthest thing from their minds was the idea that I didn’t look like a model. Both my roommate and I had been unpacking the baggage of junior high and high school into our perceptions of them; since we two were toting around dramatically different luggage, the contents spilled out into mismatched heaps.

Now, every time I post something on Facebook, and one of those girls who hurt my feelings so badly in 1985 comments enthusiastically and positively that she loves me, I blip back to elementary school, to junior high, to high school, to college, to graduate school, to my current work life. As I flash through the profound aches and wild joys all mixed up together, I think:

“The most amazing part of life might just be that we manage to live through it.”

———————————–

*Wouldn’t it be something if I’d written all that in a note, folded it into a triangle that could be finger-punted like a football, and slipped it to her as we passed in the hall?

Leave a Reply