“And I’ll meet you at our usual place,” Helen said by way of wrap-up, as she did every time we finished planning an outing.

The first time she said it, I squealed. “I love that we have a ‘usual place’! I’ve only been in Belarus for a few weeks, and already I not only have a friend, but we even have ‘a place’!”

The place was created through happenstance: it was the only unoccupied bit of street near my apartment building the first time she dropped me off.

At the end of a quick tour of the university where I would be guest teaching, I’d been introduced to Helen in one of the offices housing English teachers. After a few minutes of light chat — where did she get that flawless British accent and comportment? — she offered to drive me home. She was leaving anyhow; no bother; don’t think a thing of it.

Five minutes later, when I managed to identify which dull cement block of a building I had a key to, we discovered all the nearby parking spaces were occupied. Briskly, Helen pulled up to the curb and carved out her own space, there on the corner. From that day on, Helen never parked in a designated spot when she picked me up or dropped me off. Always, she angled her car near the junction of two sidewalks at the corner. I’d buzz out of my building, turn right, take a few steps, and see her smiling face behind the windshield, driving glasses perched upon her nose.

My family was thousands of miles away in the United States; I was navigating daily tasks without the lubrication of language; every week presented new student faces and teaching challenges; and my social life was feast or famine, swinging wildly between folk dancing in a crowded “disco” and realizing on a Monday that I hadn’t spoken aloud since Friday. But then, whenever I threatened to tip into woe, there’d be Helen, opening the car door, hopping out in impossibly spiky boots under too-short pants, her voice piping a greeting.

Not on social media, Helen nevertheless tracked me with an intuition surprising in a person who presented as “quirky” at best, “odd” less kindly. Arranging one of our first Sunday outings, she asked if I might like to attend an organ concert at the historic, restored church-cum-museum because “I have a sense you might like that kind of thing.”

When I reached The Usual Place that day, her driving glasses lay upside down on the dashboard, whisked off for the energetic greeting and the handing over of a jar of homemade jam. In the backseat, her ten-year-old son, Sasha (alternately called Sania and Sanka), nervously awaited his first verbal exchange with a native English speaker.

“Hello, Sasha,” I said, slowly, twisting in my seat and smiling.

Too shy to answer, Sasha fidgeted uncomfortably.

“Now what do you say to Jocelyn?” his mother prompted.

“Hell. O,” he managed, thick-throated.

Poor kid. I hadn’t brought anything from the States that would be particularly exciting to a youngster, but maybe he’d respond to an effort. I handed him a ball point pen from my Minnesota college, hoping somehow the glamour of “a thing from the United States that clicks!” might bring a shine to his smile.

Mostly, he wanted to continue playing a game on his mom’s phone.

“Now what do you say to Jocelyn?” Helen once again urged.

“T’ank you,” he obliged, dear in the way he’d already lost the pen on the floor.

Fortunately for him, Helen liked to talk; he was off the hook. With rat-a-tat energy, she threw the car into Reverse, backing assertively into oncoming traffic as she told me she’d been reading a mystery written in English – “Not my cup of tea, to be honest, but when there’s not a lot of choice of books, we read what there is!” – and she’d spotted the name of my hometown on page 169 – “I couldn’t believe it when I saw it because it’s not a big city now, is it?” – and – “I’ll be sure to bring it next time we meet; you’ll be amazed, too! What are the chances Duluth, Minnesota, would appear in my book? It’s only because I’ve met you!”

Her chatter continued as we wound through the city to the church. I should never be afraid to call her, day or night, if I had a problem, and it would be her joy and delight to answer any possible linguistic question that might present itself. She’d be ever so happy to show me around the area, indeed, but her weekends were often quite tricky because of all Sasha’s scheduled activities; she did like to keep him busy, lest he lapse into himself, and his hammer-throwing lessons on Saturdays after swimming lessons were improving him noticeably. Her parents were quite lovely and had been supportive when she’d turned up single and pregnant a decade before, but now she also had a life with her partner, Grisha, whom she’d met a few years earlier when her car had broken down, and he’d shown up to handle the tow. Oh, yes, she supposed I missed my family terribly, so how was I occupying myself in the free hours? I liked to bake? So did she! Was I one to make an apple cake? She would definitely give me some apples from the tree at her parents’ dacha next time we met.

By the time the car was parked just below the holy spring outside the church – “We’ll stop and have a sip; not sure I believe, but it can’t hurt. Sasha and I always have a good drink when we’re here, just to stay in good graces” – I felt I’d known Helen for years.

A few weeks later, aware of my fascination with the region’s rustic wooden houses, Helen took me – Sasha once again tucked into the backseat – to her family’s dacha, a twenty-minute drive outside the city. Originally, the house had belonged to her grandparents, now her parents, and one day it would pass to her, then Sasha. No matter who held the title, the house was a weekend escape for everyone in the family, ostensibly a country home away from the demands of regular life, but, in actuality, a place of work: the banya needed repairing; her father wanted an outdoor shower; her mother needed constant help with the gardens; the interior begged for painting.

Helen glowed with pride of place as she walked me around the small property, explaining who slept where, which stuffed animal had been hers as a child, and how many jars of berry preserves she’d helped her mother put up that summer. “This is a true cultural experience for you, Jocelyn, isn’t it? You have to understand our love of dachas and banyas if you hope to understand Belarus!”

Before we left, Helen grabbed a plastic bag from her car and spent a few minutes filling it with apples from the tree just outside the colorful fence she’d painted, explaining as she wrenched them free, “These are winter apples; they will stay on the tree until a really big frost.”

The car thunking slowly over the rutted road that led back to pavement, I tucked the bag of apples between my knees. Helen had picked perhaps 10 kilograms of them for me to use when I filled a solitary hour with baking a cake.

When we left the dacha, the slanting October light was fading to shadow, but Helen wasn’t done with me yet. “I know you like to run, and I heard you enjoy trails. Let’s stop for a few minutes at the park near the river. Maybe then in the future you can take a marshrutka from Polotsk to Novopolotsk and run in a different place. It strikes me that would appeal to your independence and sense of adventure. All you need is to know about a place, and then you make it your own, isn’t that right?”

As we walked slowly along the broad paved pathways of the park amidst a gentle swirl of Sunday-afternoon families, Sasha stuck close, not understanding much but more confident when near. The words he didn’t understand were important.

Always more than a tour guide, Helen steered Sasha out of the path of a bicyclist as she turned the direction of the conversation. “Now. I understand you’re very interested in life during Soviet times. I was a girl during the final years of the Soviet Union, so mostly I remember the ice cream, the soda machines, and the feeling that we were all there for each other. When I was a child, all the families in our group of buildings would share a meal in the communal courtyard on Sunday afternoons. Someone would put out tablecloths, and then each family would come downstairs with a pot of food, so it created, you know, the kind of thing where someone might not have much, but, together, we all had enough. And we knew each other. Maybe it’s because I was a child, but my memories of Soviet times are good ones.

What was difficult were the times that came After. The 1990s were truly terrible, Jocelyn. There was no money, no food. As many of us did and still do, I lived with my parents while attending university, and I remember my usual dinner before studying at night was a spoonful of jam stirred into a glass of water. I was talking to my mother about this, and she doesn’t remember what we ate. But I do. I was so hungry that I tried to ignore my stomach and pour that feeling into my studies.”

As she spoke, she and Sasha swung their clasped hands. Completely in sync with his mother, he hadn’t understood a word.

One afternoon, as I sat at Helen’s desk in the large office housing the university’s English teachers (“You must pop over to the pink building for a cup of tea between classes!”), she conspiratorially pulled a chair next to mine and pointed at her computer monitor.

A few days earlier, I’d asked her about a storefront that I walked past on my way home from fitness classes several nights each week. Named Wildberries, the store seemed to consist of nothing but a row of dressing rooms and a counter at which a worker stood. There was no inventory visible, so I wondered what was afoot at the Wildberries? Was it a sex shop, with curtained booths providing privacy for paid encounters involving both wildness and “berries” of several varieties?

“Oh, my goodness, NO!” Helen giggled, washed warm by the unaccustomed nonsense of a silly girlfriend. “Wildberries is a popular online shop, and they send your order to the store in your town, where you can try on the items to see if they fit. If they don’t, the worker returns them for you.”

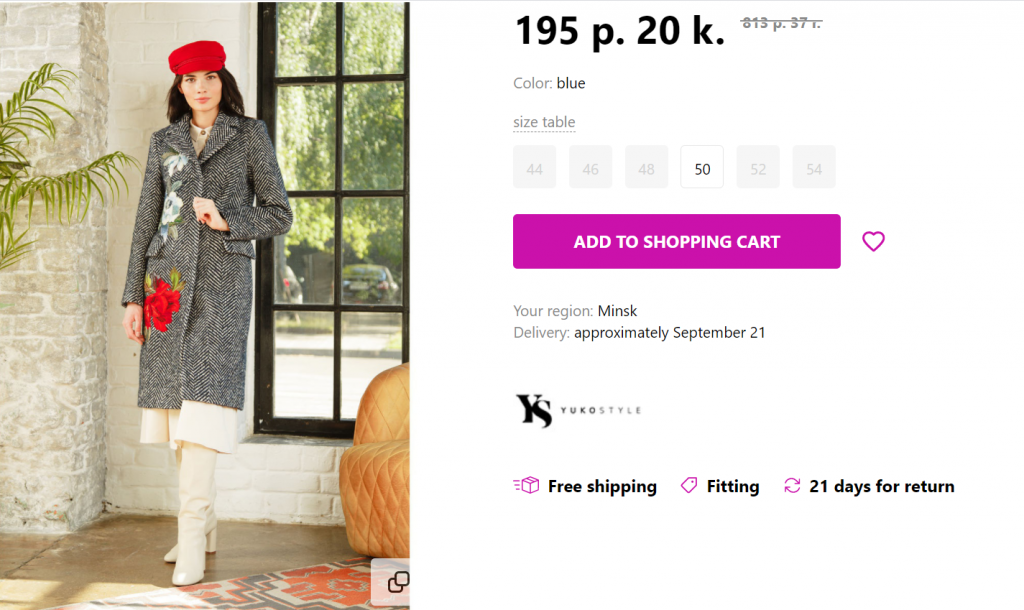

Pushing half a bar of chocolate toward my teacup, Helen began pointing at the screen in front of us. “Now, you know I told you Wildberries is a very good shop – I get many of my clothes from it – and since you asked me about it, I’ve realized they have many items that strike me as just your style.” Her finger landed upon a coat appliqued with an enormous, monstrous flower; my nose wrinkled involuntarily. “Now, doesn’t this look just like you?” she beamed.

The next few minutes afforded the opportunity for me to practice soft diplomacy skills – neutral hmmms and ohhhhs and “Yes, that certainly is something” – as Helen selected and effused about tragically ugly coats that she pegged as perfectly my style, each off-target suggestion confirming the kindness of her heart, the perfect kookiness of her taste.

Eventually, a quick glance at the clock told Helen it was nearly time for her next class. Gulping the dregs of her tea, gathering to her chest a stack of books and papers, she began planning our next meeting, “Now, really, we do need to have you come visit my classes one day, but first: there are some English teachers at a gymnasium in Novopolotsk who are wondering if you could visit and talk with them, just a relaxed conversation about teaching – no need to prepare anything. It’s Sasha’s school, the same one I attended, and it’s quite a good place. If it’s all right with you, shall we arrange it? I’ll drive you over and would be quite curious to hear what you have to say.”

Yes, of course, we should arrange it. Like Helen, I’d be quite curious to hear what I had to say. And how could I disappoint a friend who believed I’d be stunning when appliqued with roses?

Breathless and tipping into a swivet, I stood at the front of the classroom, pinned there by the gaze of twelve expectant English teachers, three “lucky” students, the gymnasium headmistress, and Helen. Each teacher had a notebook open on the wooden desk in front of her, a pen at the ready. Apparently, someone would be conveying content worth recording. Off to my right, near three “lucky” students, sat Helen. She, too, was opening a notebook in preparation for some serious jotting.

A few minutes earlier, she and I had been speeding across the ten kilometers separating Polotsk from Novopolotsk, Helen assuring me I had no need to be nervous, as the intention was that the gymnasium teachers and I would have a relaxed colleague-to-colleague chat about our methods and challenges in the classroom. Pleased that I wouldn’t be responsible for creating and carrying the energy in the room, I relaxed; this once, I wouldn’t have to perform to a crowd of diligent language students eager to test their book studies against actual usage.

I shouldn’t have relaxed. When we walked through the doors of the gymnasium, three girls in traditional costume – flowered wreaths perched upon heads – were poised expectantly, one cradling a loaf of sweetbread on a towel. The taut anticipation of their postures implied they’d been waiting in position for at least ten minutes, practicing a formal greeting that began with “Dear Jocelyn…” Nearby, holding a long-lensed camera, the headmistress hovered nervously. This was a big day for her institution.

After clapping for the accomplishment of their well-rehearsed greeting, I clutched the loaf of bread, the first of several gifts, as we all clipped down the hall, up some stairs, and down another hall, Helen translating my fervent exclamations of admiration while under-her-breathing wry comments about Sasha’s teachers and the complicated personality of the woman we were following. The flurry continued as we dropped our coats in an empty meeting room before following the headmistress, well able to reach high speeds on linoleum in four-inch heels, through another door.

Then, suddenly, as though thrust naked into the circle of a spotlight, I stood alone at the front of a classroom, thirty-four eyes locked on my face, pens poised to record my utterances.

I had nothing.

However, I was three months into being treated as a celebrity guest when, behind my too-big smile, I knew the truth: all I was good at was watching Outlander alone on my laptop and bracing myself to answer the Russian-speaking cashier’s scripted questions at the grocery store.

Even a false celebrity hates to disappoint, so, brain racing frantically, I launched into an explanation of my name and names in the United States and how confusing patronymics are to the English-speaking world, and as I contemplated drawing a game of Hangman on the board behind me, I realized none of the teachers was taking notes –except kind Helen, she who could find a sliver of meat on a bare bone, was scratching words into her notebook as though there was merit to my blather. Several times, I tried asking questions of the teachers – tried turning my talk into something like a discussion – but everyone was too intimidated, too accustomed to passivity, to venture a response. Eventually, thinking once again that the memoir of my professional life will be titled Sweaty and Panting, I wrapped up and thanked the assembled blank-faced crowd for inviting me to their school.

This verbal curtsey cued the room to exhale. I thought my shutting up meant it was time for handshakes and superficial niceties, but, instead, we moved on to the next item on an agenda I didn’t know existed. Twenty clicks of the headmistress’ heels later, I walked into a classroom that had been set up for a tea party. Wishing I were fueled by more than three hours of sleep, I powered into small talk with the English teachers who were reaching hungrily for cakes and biscuits. Just as a few of them quietly began to speak, the door opened, and in walked a boy with a saxophone. For the next fifteen minutes, as besuited adolescent Pavel played hits from the 70s, conversation was impossible. Muted, we sipped. We chewed. We applauded. We attempted to exchange a few hushed phrases during his inhales.

But Helen turned herself away from the table to face Pavel. Raptly, as though she’d never before considered that hoooonesty is such a lonely word, she, mother of a son just about Pavel’s age, gave the musician her full attention, her posture countering the unsung lyrics. With Helen in the room, it was impossible to believe that everyone is so untrue.

The most common method of getting from city to city within Belarus is mini-buses, but I learned early on that these marshrutkas – from where to catch them (“. . . about a hundred meters down from the pink door across from the small mall, near the bench with the picture of an ice cream cone on it, but that’s actually the stop for the marshrutka to Grodno; if you want the one to Polotsk, you need to go out back of the train station – there’s construction, so you’ll walk around the long fence line and then cross a road, and there are maybe eight different marshrutkas to different cities there, so then just be sure you get on the one that says Novopolotsk”), to how to tell the Russian-speaking driver where you want to get off (“The driver won’t stop in Polotsk unless you tell him to; otherwise, he’ll just wing through the city and head over to Novopolotsk, which is where pretty much everyone gets off”), to how and when to pay (“It’s ten rubles. No, wait, I think thirteen. You can pay the driver when he stops at the midpoint, usually a gas station so he can have a cigarette, unless it’s a different driver who doesn’t smoke, and he might want you to pay at the start”) – were tricky business for newcomers. Thus, after a few high-stress marshrutka moments, I decided it would be worth figuring out how to take the train. It cost more, but I could purchase tickets online, and there would be no mad scramble to suss out pick-up and drop-off points.

With a conference in Minsk looming, I booked my tickets and, to allay worry, took myself on a pre-travel scouting mission of the train station near my house. How hard could it be to figure out platforms and directions?

I first floundered when I couldn’t figure out if the grand-looking building with ticket booths and people getting on and off trains was the station I’d be using – or if I’d need to go next door to the plain square box of a building, also with ticket booths and people getting on and off trains. Bewildered, slowly sounding out the Cyrillic on various signs in the grand building, I felt a low-level anxiety start in my stomach. Okay, if I couldn’t decipher what trains frequented the fancy building, maybe I could narrow things down over in the plain box station. Except no. While there were definitely more people hanging around in the plain box, many of them clearly waiting to depart, a quick turn inside the building only confused me more. Where did they go to get to the platforms? Why were there both humans behind plexiglass and machines on the wall dispensing what looked like tickets? If I bought my ticket online but didn’t have a printer, did I need to somehow get a paper copy? If a train left Polotsk heading south at a rate of 100km per hour, and another train left Minsk an hour later, heading north at a rate of 80km per hour, how many hours would it take for me to get booted out a side door for lack of proper documentation, my body slamming into the northbound train as we rounded a bend?

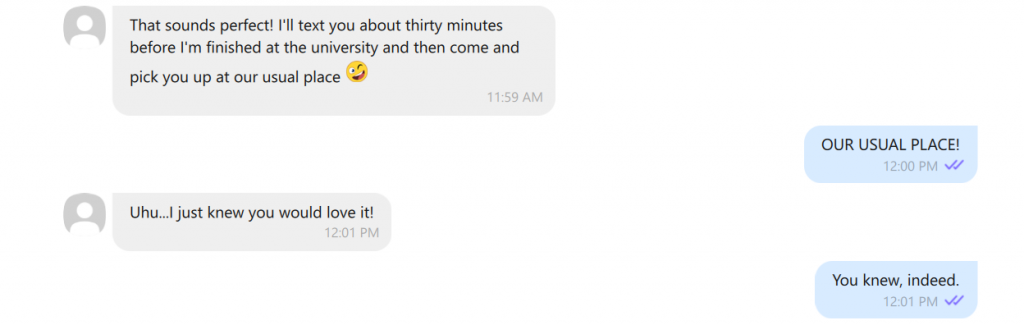

Never proud, but especially in the role of bumbling greenhorn, I asked a few of the English teachers the next time I was on campus; of course it was Helen who offered, “What time does your train leave? I can come to Polotsk for some errands, and then I’ll meet you at our usual spot. We’ll walk to the station and make sure we get you to the right track well before departure!”

When the time came, however, it wasn’t enough to point me to the train. Carrying my backpack, she located the correct car and stepped inside. “They don’t mind if I come in with you to see you to your seat. We always do this in Belarus with our family. It is our way.” Briskly, Helen located my seat, helped me store my bags, and scouted out the bathroom. Watching me settle into my assigned seat, she worried: “Will it make you sick, to be sitting backward to the motion? For me, it’s bad news to face backwards. My stomach and head need to be looking at what’s coming!”

As we messaged one evening, making a plan for Helen to drive my visiting family and me to the university in the neighboring city with a load of donated books, she interposed, “By the way, I’m making a cheesecake. What are you doing?”

Sitting next to my cross-stitching husband, I told her.

Her reply was an ammonite spiral of enthusiasm and self-deprecation: “I love cross-stitching, only there’s absolutely no time. The last one I did was nine years ago. And today I didn’t even find time to do a bit of studying with Sania. Shame on me!”

Attempting to bolster, I noted, “In your defense, you did make a cheesecake today, though!”

Her spirits refused perking. “Not quite – it is still in the oven. And to tell the truth it does not look good somehow. Something must be wrong with it. I am at a loss.”

Ever one to jolly, I joked, “Maybe the cake is being judgmental because it thinks you should have helped Sania study instead.”

The tone of her reply was uncharacteristically forthcoming. “You must be right. But still it makes me sad…Today has been not my day…I hope. Because if this is my day then I’m afraid to imagine what can be not my day.”

Committed to the jolly, I pepped: “Fingers crossed that it tastes better than it looks. And let’s say this is not your day – because if this is as bad as it gets, you are living a lucky life.”

“Yes, you are right,” Helen agreed, adding, “I am ungrateful. But that it is our national sport in Belarus – complaining and moaning. I find it especially endearing when I hear it from people living in detached houses and driving luxury brand new cars. They do it to perfection.”

Cultural commentary aside, Helen’s self-condemnation was atypically bare emotion. I rushed to reassure: “You don’t sound ungrateful at all – but it’s okay if your cake is tragic so long as the rest of your life isn’t.”

“That’s right,” she conceded. “It’s just that I really made surprisingly many mistakes today so I’m honestly feeling a bit inadequate. Let’s hope that tomorrow will be better.”

Uncomfortable and exposed, Helen stiffened her upper lip and wheeled the conversation back to neutral territory. “The cake is coming out of the oven any minute now. Treacherously, it smells good.”

Then she added, “It’s nearly done, but it’s supposed to be darker. But maybe it’s not that bad, after all.”

That coat. Actually, that hat. Wow.

When I met Helen in front of the big hotel that day, she was hard to miss. Eastern European women love fur, but Helen’s look conjured “Amelia Bedelia” more than “chic,” quirky oddball sniffing pillowcases more than leggy glamazon quaffing vodka.

I’ve always loved Amelia Bedelia. But I never imagined I’d have an afternoon date with a bearlike Bedelia, first to the post office where my furry companion would help me pick up a package, and then to the cafe that served Soviet-style ice cream, something that made everyone over the age of 30 dreamy with nostalgia.

Complimenting Helen on serving serious style, I noted that her hat, in particular, was interesting.

“Oh, thank you very much, Jocelyn! You’ll never see another like it! I designed it myself. My mother used to wear the coat, but when I had it remade to suit myself, there was some fur left over, so I sketched out an idea for a hat. The man at the shop asked me, ‘Are you sure you want this hat?’ when I gave him the sketch, and I assured him it would be lovely. The hat with the coat are really quite a charm, aren’t they?”

Yes, dear friend. Like you, they are unquestionably quite a charm.

“My students are howling for you, Jocelyn!” Helen messaged. “When can you visit them?”

Since Allegra and then friend Mary Beth were due to arrive in Belarus the following week, we hatched a plan, plotting two “roundtable” class meetings – a democratic physical arrangement foreign to the traditional teacher-up-front model of Belarus education. “We are more like the Chinese in this respect – when the alpha person is around it’s considered impolite to be forthright and active,” Helen explained, frustrated by rooms dull with passivity.

“Well,” I ventured. “Since we aren’t preparing anything and are forcing eye-to-eye conversation, maybe your students will want to ask Allegra about studying Russian in the United States.”

Helen agreed, adding, “About this, and about what tea young people in the States drink, and what cosmetics girls use…”

Predictably, when the first roundtable discussion occurred, the students, eyes down, were reticent. They’d been asked to bring in examples of jokes, so as to compare them to American humor. Speaking quietly to the table top, student after student mumbled jokes about fishermen, drunks, and too-tight shoes as Helen enthusiastically urged them to speak up! explain! ask questions!

Two days later, when Mary Beth joined Allegra and me for a second roundtable discussion with the same students, the mood was more relaxed – democracy is not built in a day – as we considered the cultural connotations attached to colors. By the end of an hour and a half, having held ideas of “White Russia” and “blue wave” up to the light, we felt ourselves among friends.

Students hustled to their next class, and Helen took the Americans into the English department office, offering a quick cuppa in the five minutes before her next class. Since we had an appointment at the migration office to register Mary Beth’s presence in the country, we hadn’t much time to chat. However, there was still one thing I needed: language help. The drain in my flat’s bath tub had been sluggish for months, but it had nearly gone on strike in recent days, overwhelmed by the demands of three bodies. Previously, I’d bought a drain unclogging product in the grocery store, but it had proven even less effective than Boris Yeltsin. I needed a stronger unblocker.

Naturally, opinions in the English office varied; faculty have strong opinions about hair dissolvers, but one thing was clear: I needed to go into a hardware store and ask a round-bellied man, in Russian, for a drain unclogger.

As someone who lacked even basic verbs and pronouns, I found the prospect of this errand daunting. I can’t even tell the nice man where to stop the bus, but you want me to say “drain unclogger” in Russian?

Fortunately, I had a Helen.

As the day neared for me to depart Belarus, there was some debate over who would see me out of the city. Initially, it seemed my massive bags and I would have to carve our own way to Minsk, to a hotel, then to the airport. Fretting, I asked Helen if she knew of any driver I might hire to make the journey easier. The reply was immediate.

“I do know someone – that’s my Grisha. Did I mention that he works as a driver for OSCE [Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe] elections missions when they come to Belarus? So that’s the route he normally does! Do you want me to ask him?”

Helen had talked to me several times, in fact, about the OSCE’s oversight of Belarus’ problematic elections, suggesting that I might find a way to return one day as an OSCE volunteer. The idea of being chauffeured to Minsk by a seasoned “mission driver” spiraled me into visions of discovering illegally offloaded ballot boxes at a rest area when we stopped for cheesecake and tea. Ooh. I definitely wanted my exit from the country to entail cake in one fist, illegally discarded ballots in the other!

Alas, the vice-rector at the university stepped up and put her slick, chic, wow work vehicle and chauffeur at my disposal. Instead of Grisha and me exposing a corrupt regime while refueling at the midpoint, it seemed I’d be coasting to the capital in fine style with a driver named Vanya.

Still, Helen had some overdue errands in Minsk and would tolerate a lesser Vanya if it meant checking them off her list. Eagerly, she offered to accompany me in the car on the day I left my adopted city in the rear view. At the same time, it turned out, other friends were lining up an escort in the form of a different beloved colleague. Would this tussle over anointed car companion come to fisticuffs? Had this small former-Soviet country ever seen two English teachers arm wrestle about anything other than the abiding controversy that would is, no it isn’t, yes it is, a modal verb?

When the dust settled, Helen emerged victorious, her pert self showing up at my apartment building early on the designated morning, as did the runner-up, Elena (no sore loser, that one). Both benefitted from a last-minute walk-through of the flat. Would either of you like this stepstool? (Elena, modally, would!) Who needs a desk lamp? (Sasha did!) Would anyone like this raincoat? (Helen, modishly, would!)

I was shaky that morning, poorly rested, emotional about leaving this place that had filled some of my potholes. Fortunately, Helen’s efficient manner brooked no nonsense, so my pieces clung together. “I’ll sit in the front with Vanya, to keep him company and awake. Do you suppose he will be cooperative? Will he stop on the way for us to grab a bite? We shall see. Here now, take my coat, will you, and put it on the seat next to you? It will be terribly warm inside such a gorgeous car, I’m sure. I have a few errands to run in Minsk, so I must work on the driver about that. There is one special grammar book I must have for a project I’m working on, and I can’t find it anywhere. Minsk is my hope!”

Although I’d been instructed to use the three hours to nap, I filled the time by writing generic heartfelt generic greetings inside the front covers of notebooks that university students could win in the future at English club meetings. My head heart, my heart ached, my hand moved. Periodically I glanced over at Helen’s coat on the seat next to me, a deflated bear basking in the sunshine.

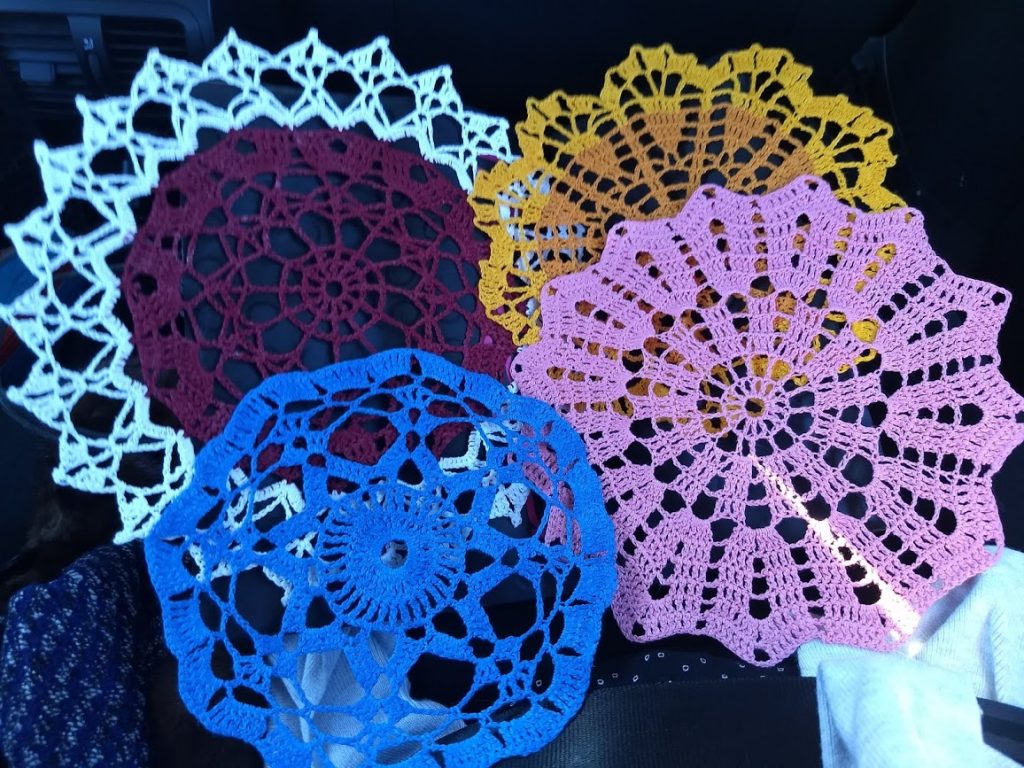

My forehead rested against the coolness of the window when Helen turned around to face me, paper bag in hand. “Now I just have a small gift for you and your family so that you can always remember Belarus.” She sniffed brusquely. As I pulled out four colorful doilies, she added, “I know you like our traditional crafts, so I made you something with my hands. The colors are meant to suit each member of your family, but perhaps their preferences will surprise, eh? Most important is that they’re light and small; even in your heavy bags, you’ll find a spot for these.”

I hadn’t dared touch the deflated bear, but my hands were drawn to the circles she’d crocheted. I’d never much been a doily person. Suddenly, though, I was very much a doily person.

By the time we reached my hotel in Minsk, we’d talked about Sasha’s hammer-throwing lessons, who would meet me at the airport in Minneapolis, and how I would send her the much-needed grammar book if she couldn’t find it in Minsk. “I’ll come in with you, Jocelyn. I’ll help with your bags and see you settled before Vanya and I carry on.”

As the stern-faced clerks at Reception looked over every page of my passport, the full weight of exhausted transition landed on my shoulders.

“Of course, I’ll take you up to your room. We’ll make sure your key works and get your bags handled,” Helen assured me.

The key worked. The bags were handled.

“Well, now, you have a good trip home and message me when you land,” she told me brightly, patting my arm, stepping into the hallway.

My sudden onslaught of tears startled us both.

Ugly with it, I sobbed.

Helen was the last thread connecting me to all of them, to all of it. When she left, it would be over.

I dashed at my eyes with knuckles. “I’m sorry. It’s just…this whole experience has been so special…and you’ve been just so…” I grabbed her and leaned in.

Her eyes widened with alarm. She stepped backward, into her own space. “Yes, well, uh, clearly you need some rest, and Vanya’s waiting. We have several stops to make before returning, so I’ll just say goodbye. Please tell your family hello when you see them.”

Oh, right. I straightened up, stepped back, blinked. “Yes, yes, that’s just it. I’m definitely over-tired. You have a safe trip back to Novopolotsk tonight. And thank you, always, for everything.”

Nervously, Helen smiled as she, topped by that offbeat hat, took a few hasty steps away, fur coat swinging. Nodding curtly, she added, “Do message if you have any problems. Any hour. It’s never a problem.”

Then she was gone. I was alone. It was over.

Later that night, she sent a message. She was home. The next day, she checked in to see how my day at the embassy had gone, to make sure I didn’t want her to call a former student in Minsk who would be more than happy to accompany me to the airport the next day. The day after that, I flew. When I turned on my phone at the baggage claim in Minneapolis, there was a message from her.

Helen was maternal to the end.

I’m writing this, of course, because then she died.

We kept up our messages for the next few weeks as I stumbled through the rooms of our house in Duluth, bleary with the shock of return. I’d been on a fantastic adventure to a land where people did 32 things with potatoes, where freedom genuinely was “nothing left to lose,” where even Stalin couldn’t kill the generous hearts – and then, suddenly, I was back at my same old puzzling table, trying to find the straight edges.

It was a comfort to chat with Helen as I readjusted, to assure myself the Fulbright months might be over, but the people, the friendships, remained.

Two weeks before I received the first message that something was wrong, I sent her that grammar book.

Two days before she’d suffer something first described to me as “a blood stroke,” she asked if we’d named our daughter after Lord Byron’s daughter.

When I told her we’d gone to watch Allegra run, she wondered what a “meet track” was.

She’d gone back to the Soviet-style cafe and had a milkshake — the pear kind — just as we had done together.

Thirty-six hours before she’d suffer a brain aneurysm, she waxed excited about a podcast on which I talked about my Belarus experience.

One day before her brain would hemorrhage, and she’d lapse into a week-long coma from which she’d never revive, Helen signed off with an idea. It was her mother’s birthday, and the family would be eating out that night at a restaurant.

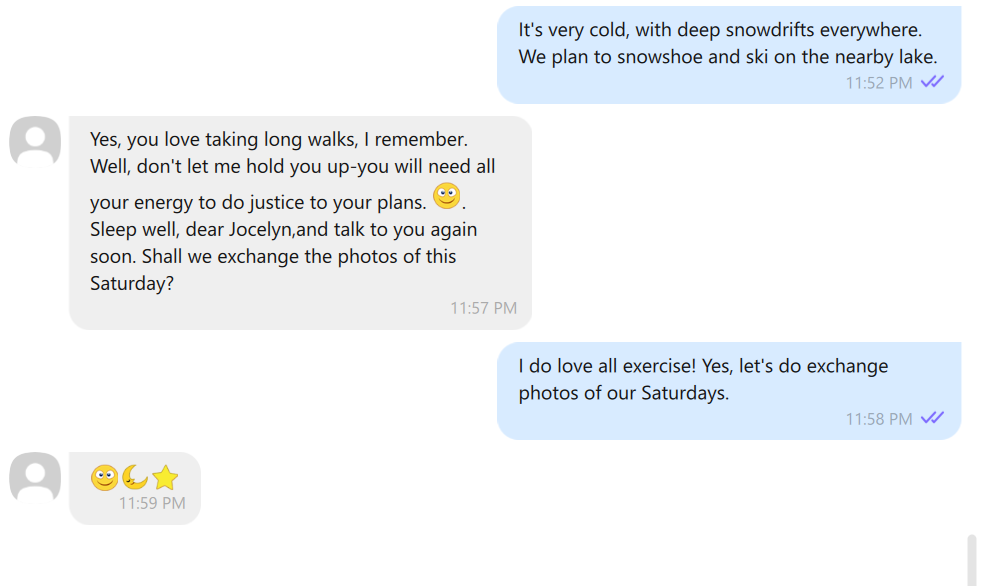

“Sleep well, dear Jocelyn, and talk to you again soon. Shall we exchange the photos of this Saturday?”

Oh, yes. We should share photos of our Saturdays.

The pictures were never sent. In the ensuing days, I’d receive messages from Vera, from Olga, from Archie, from Rita – had I heard? did I know? that my friend? and poor Sasha? what of Grisha? her students? her parents?

The real, dramatic events of losing Helen were strangely abstracted for me. She was there; I was not. So long as I wasn’t there, it never had to be real.

So long as Belarus lives in my memories, Helen – sipping water from the spring, harvesting apples, showing off her family’s dacha, explaining hunger after The Fall, embracing borderline taste, doting on a besuited saxophone player, seating me on the train, challenging students, loving language, dodging a hug, wishing for more time – lives, too.

I picture her now.

I turn the corner of the cement-block building. There she is, her car idling. She spots me; her face brightens. Leaping out, she cuts a memorable figure in her tight leather coat and stiletto heels. As I near, she calls out.

“I am awfully pleased with myself today – I did some internet shopping and was able to buy a pair of wonderful winter boots for Sasha. And they were not made in China!”

I grin and get into the car. Let’s hear about those boots.

Leave a Reply