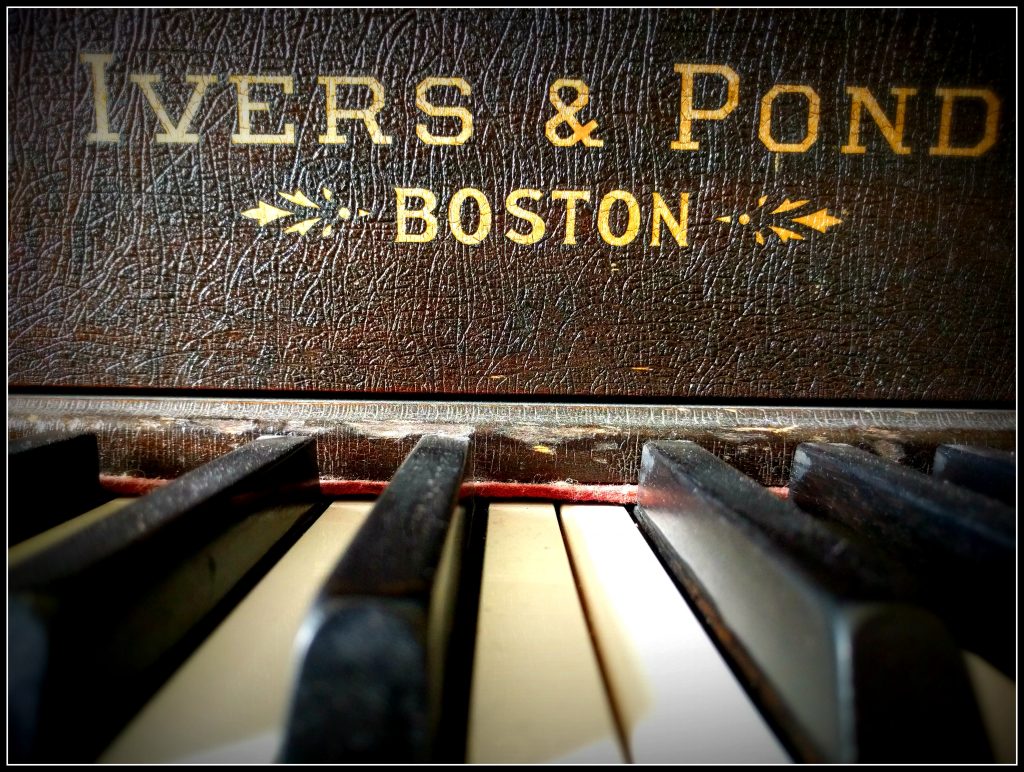

As I run the wet paper towel back and forth, thin lines of dust — dark worms of motes and lint — twine into an abstract portrait of neglect.

By the time I get to Middle C, I have refolded the paper three times, burying the filth, wrapping my fingers in new inches of pristine fiber. After each octave, I refold, lazily hoping there is enough clean towel to get me to High C.

It’s been 11 weeks since I touched the piano; I can see my fingers’ absence in the dirt that I’m rubbing from white keys — up to black — down to white — up to black. Eighty-eight times the towel leaps a crack, heaves higher, drops lower, scours the terrain, plinking out an uneven, deliberate dirge of inattention.

A few minutes earlier, restlessly waiting for the next in a series of rain showers to blow over so that I could go for a walk, I’d plopped down on the piano bench. Put my hands on the keys. Felt the gilings of disuse.

There are a variety of books on the music rack, but the one on top is open to Beethoven’s “Für Elise,” that playful, flowing, mood-shifting bagatelle. In recent years, I’ve put countless hours into establishing a relationship with it. In recent months, however, I’ve put no hours at all into nurturing the connection between notation and my brain.

Even when I have been playing, I’m a slow and lurching child at the keyboard, hacking my way through the measures, taxing the patience of listeners with expectations.

After my weeks away, “Für Elise” is an upright, outright challenge. But I have a few minutes, and I’ve been missing the piano; as my shoulder has healed post-surgery, I’ve gradually inched back into daily activities — extending my hand to turn on the faucet, driving, washing dishes, scrubbing the top of my head with both hands in the shower, pulling off my shirt with two hands — and slowly added in hobbies that bring pleasure — cobbling together a jigsaw puzzle, playing frisbee in the yard with Paco, gardening, going to the gym. Yet I still haven’t gone near the piano.

My brain hasn’t had the space for it.

Sitting down on the piano bench signifies something. It means I’m feeling fine. It means I have surplus energy that wants channeling. It means my mind fancies a float away from the verbal, my ego is in the mood to giggle at my fingers’ misadventures, my spirit pirouettes whimsically, my spine hankers to represent with its best posture, my skin craves the tactile pleasure of rubbing against the smoothness of ivory. When I play the piano, I am reconnecting with my younger self, with the girl who, from ages 7-16, slid her way around practicing, who did well enough but never cared to push into her potential, who hated playing for others, who cried her way through recitals. At the piano, I am surrounded by my father’s echo, the faint reverberation of his elegant fingers striking a chord followed by a resonant “Ah-ah-ah-ah” — the warm-up scales during private voice lessons floating from the living room through the slatted doors into the kitchen where I dug in the pantry, looking for a snack.

As an adult at the piano, I am trilling my way through more than notes on the page.

Foreseeing decades of future diminishments through the lens of a painful, limited shoulder, I realize sitting down at the piano is meaningful. In that quick breath of a moment before I start to play, I am tense with the tenses: I am everything I used to be, everything I am, everything I will be.

I haven’t touched the piano in 11 weeks because I can’t be a shell of myself when I attempt “Für Elise.” If I am feeling wan, infirm, shadowy, the music will defeat me, and I’m one for whom music’s beauty is in the rise.

But then a rainstorm comes. I have a few minutes. I’ve been missing the piano.

And I’ve been feeling fine.

Pulling my clavicles together, positioning my elbows in front of my ribs, curling my knuckles, I scan the opening measures, realize the right hand will be a cinch: I play those notes in my head as I try to fall asleep. Preparing mentally for the left hand’s entrance, for handling more than one thing simultaneously, I examine the first three bass notes of the composition. An easy run. Starting with my left pinkie on a low A, I will roll upwards.

Spine ramrod, I begin. Five notes in, I hear Byron’s voice bark involuntarily in the kitchen. He’s talking to himself, has just exclaimed, “Oh, good!”

Later, he will tell me, “I was so glad to hear you play the piano. I’ve been waiting.”

In the moment, though, the kitchen exclamation doesn’t register. I’m trying to deal with the left hand’s entrance while keeping my right hand in motion.

I mess up.

Try it again.

Whoops.

Stupid bifocals. The notes look funny on the page. The keys aren’t where my hand expects them to be. Moving my gaze from page to keys is dizzying. Stupid bifocals. My glasses are stupid, but they are no excuse: I first went into bifocals the year I started playing piano, when I was seven.

Then. There. I’ve got it: the run of three easy notes. My fingers are clumsy, and a yell forms inside my skull when I recall that three easy notes, which weren’t easy at all, are only the beginning. As is always the case, once I start playing, once I engage with what’s in front of me, my heart accelerates.

It’s almost annoying that the first measure isn’t everything. Always, there’s more. The challenge keeps coming, flooding my synapses, snatching my breath — the notes flowing predictably, then unpredictably, taking me through repeats and new variations. I know this song intimately, but I’m so rusty it’s like I’m sight reading.

What’s coming out of the piano is terrible. Were he leaning back in one of the dining room chairs, sipping a cup of chai, dipping biscotti into its depths, marveling at the transformation wrought by his new cochlear implants, Beethoven would be hard pressed to recognize his composition.

What’s coming out of the piano is beautiful. No matter how leaden or inept, live music pouring out of an instrument revolutionizes the room. Textured, layered, raw, real, unpredictable, emotional — live music is tangible in a way that recorded never is. It affects us differently, materially, these notes being played by an actual person in an actual space. My terrible “Für Elise” enriches the air, smashes invisible tensions.

Without question, my terrible piano playing is gorgeous.

It’s significant.

It means I’m fine.

After a few pages of glitchy bumbling, I am overwhelmed. Exhausted. I’m fine, but with limits.

So I stop. I’ll be back soon.

But first: I need to wipe the dust off these keys.

If Beethoven sees this filth, he’ll throw a fit.

And my shoulder, even though it’s coming along, isn’t up to scrubbing splattered chai off the sideboard.

—————————————

Leave a Reply to Secret Agent Woman Cancel reply