My grandmother, Mildred, was born in Sioux City, Iowa, in 1902. She died in Windom, Minnesota, in 1974.

During the 71 years of her life, Grandma moved frequently, particularly during her youth, as she was the daughter of a Methodist pastor. Moving within Iowa and then to South Dakota, the family uprooted in 1904, 1905, 1907, 1908, 1909, 1911, 1915, 1917, 1920; three younger siblings were added to the family at various points in the geographical shifting. Because of childhood illnesses, Grandma’s schooling took longer than it might have. After graduating from high school in 1922, she attended Drake University for four years. In that time, her parents moved twice. Once she had her degree, my grandma taught, took more courses, and traveled, in the process relocating at least seven more times. Eventually, in 1933, she married my grandfather, Julian, and they started their own family, living out the rest of their years in small-town southern Minnesota.

Sitting here, decades later, I try to imagine her life, as it must have felt to her. It’s impossible to know anyone else’s experience, of course; even as we live out our own days, it’s often incogitable to understand events as they’re happening. In the moment, it just is what it is, with perspective being the benefit of time and a larger sprawl of context. For my grandmother, frequently changing house for the first part of her life was the norm. She was a kid. When her parents announced, “We’re moving to Smithland (or Castana, Presho, Tripp, Armour, Henry, Salem, Doland, etc.),” Mildred most likely shrugged, looked for her favorite doll, and strapped on her shoes.

Later in her life, after she married and therefore stopped moving every year or two, how did that feel? Again, was it just “what it was”? Or was there a sense of shifting gears, of enjoying being settled, of chafing at being settled? Did she ever find it dull to wake up, year after year, in the same rooms, talking to the same people? Or was that something she’d always craved? Then again, even when her family moved frequently, she was always surrounded by the same people: her parents and siblings. Thus, in a way, she’d had stability in the midst of change. In that way, perhaps being settled felt the same as moving.

Even in the recordings of Grandma’s life events and in the notes my mom and Aunt Geri took when they questioned her about her memories, the emphasis is on dates and places, with anecdotes mixed in–undoubtedly, the focus is on the what more than the why and how. We know such-and-such happened, but we don’t necessarily know how my grandmother felt about it or what the motivating factors were. Why, for example, did Mildred’s mom and dad take a claim 15 miles outside Presho, South Dakota, in 1907, live in a tent and tar-paper shack for 16 months while building their “house to retire in,” and then move to Tripp, South Dakota, in 1908? I can’t help but wish for the story behind those numbers and place names.

Because I am fascinated by emotion and psychology, the moments in Mildred’s recollections when she does note her feelings are highlights. For example, it makes me grin to know she was a youngster who was proud of her sunbonnet–before she dropped it down the hole being dug for a new outdoor toilet:

Ultimately, when we look back on the lives of our forebears, at history in general, it’s all piecework–taking this tidbit and that chunk and laying them out in a pattern that makes sense, given what’s at hand. We stitch the names and dates together with words, speculation, recollection, and possibility. Then, when all the tidbits and chunks have been stitched together, there is a story. Someone else might look at the same tidbits and chunks and, in the creative process of making decisions, stitch them together into an entirely different story.

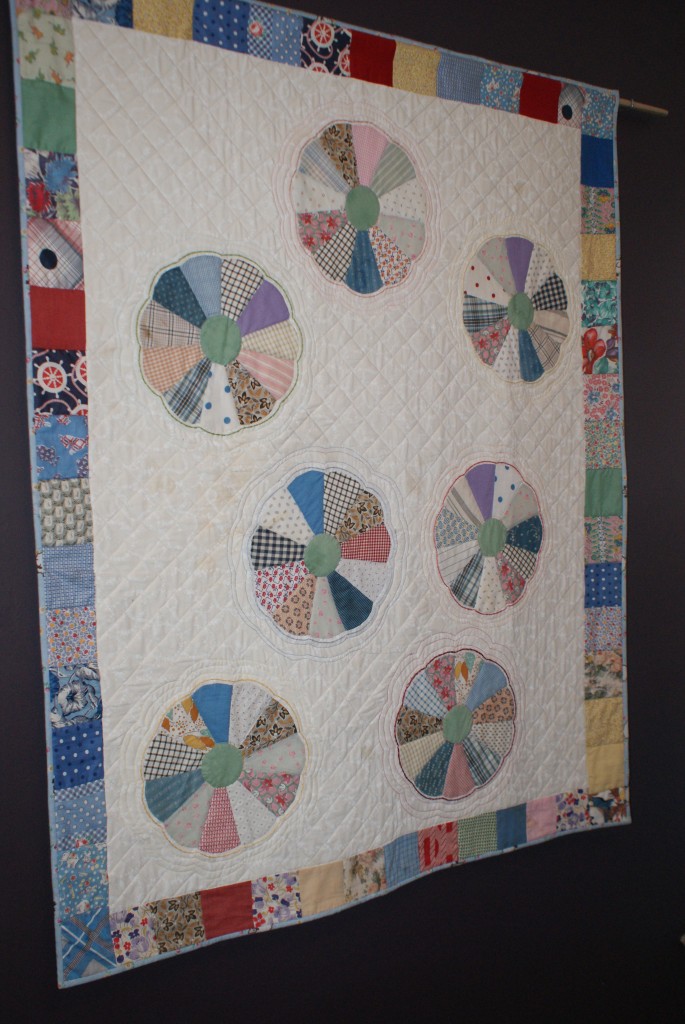

Again, my grandmother provides an illustrative example. After she died in 1974, when her children were sorting through her effects, they found a quilting project she had started: a stack of circles in the classic quilt block pattern known as Dresden Plates. The fabric in the quilt blocks and rectangles she had cut for borders were scraps of Mildred’s old house dresses–as my mom explains, “That is, dresses for staying at home and doing household chores or going down the alley to visit a neighbor lady and taking a few cookies or whatever–often with an apron over the dress. There are no Sunday-go-to-meetin’ fabrics” in the quilt. Supplementing the material from her house dresses were bits from blouses, aprons, soft toys, and fabric from a church rummage sale.

Before she died, Grandma had drawn the pattern, cut and sewed the plates (29 of them), and joined together the rectangles for the quilt’s border. After she was gone, the promise of her project remained, for she had laid out a basic framework, enough that another quilter could pick up the pieces and carry on.

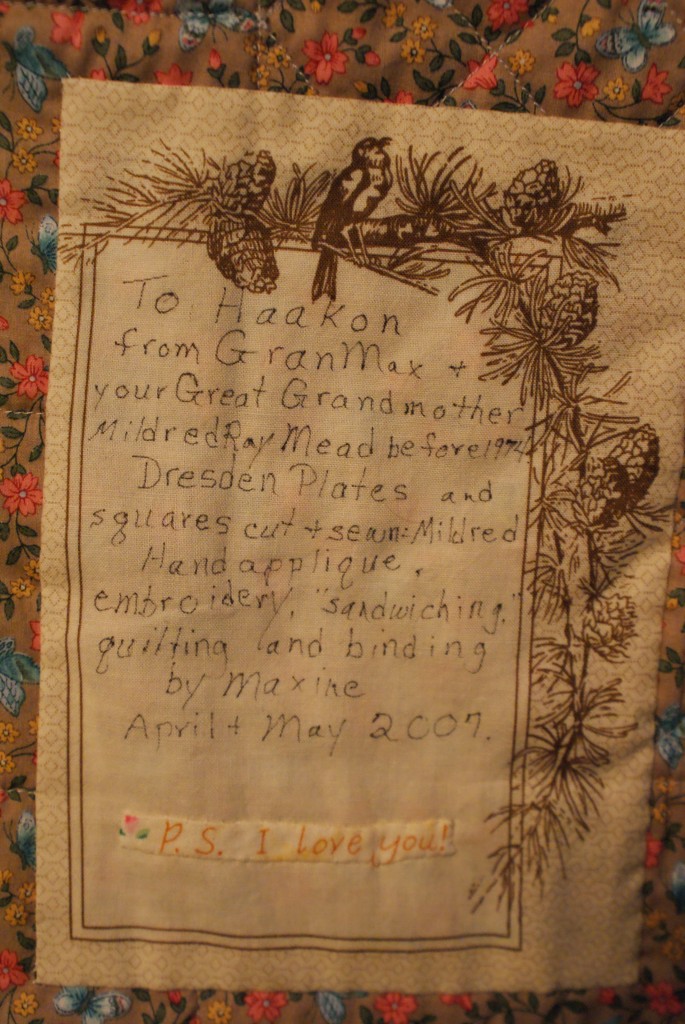

Fittingly, the project passed from mother to daughter. My mom, busy living her own life, racking up the names, places, and dates that are the scaffolding upon which a life story is hung, carried those Dresden Plates with her for decades, from one house to the next, from city to the next, from one state to the next. Eventually, she turned her attention to creating four wall hangings out of the plates, one for each of her four grandchildren.

In this way, in this manner of fashioning a tangible legacy, women’s handiwork has profound power.

In the early 1900s, a girl named Mildred in the American Midwest learned from her mother how to make stitches. That girl grew up and had her own children, one of whom was my mother, Maxine. In 1939, Mildred taught Maxine the basics when they made a doll bed quilt alternating rectangles of colored and off-white fabric. Maxine hand pieced most of it, and Mildred tied it. In the 1970s, Mildred began assembling Dresden Plates for a quilt. In the 2000s, four decades later, Maxine picked up her mother’s start and carried it forward. In 2007, my mother gifted each of my children with one of these:

Leave a Reply