A long-simmering conversation has reached a boil this week in Duluth; everyone’s a’poppin’.

I mean, I wasn’t a’poppin’ because I don’t read the newspaper, and I try to avoid public conversations because they invariably make me hate people, but I discovered just how buzzy folks were getting when questions started hitting my DMs, and every other Facebook post I saw from locals was in search of a sparky comment thread. “As an educator, what do you think?” “As a parent, what do you think?”

To be straight-up honest here: once I read the article that’s got everyone up in arms, I pretty much shrugged and thought, “Um, good? Is ‘good’ enough of a response?”

But, of course, if conversation is to happen, elaboration helps. So after I read the article about how Duluth Public Schools will no longer be requiring students to read and discuss To Kill a Mockingbird and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, I tried to work up the energy to engage in discussin’.

Mostly, though, “Good” sums up my feelings.

Whether to include classics that use racist language as part of the school curriculum is a debate that’s been raging for decades. That some action is finally happening indicates policy might be finally catching up with the current climate. Yes, people love these books. Yes, people worry that we’re erasing history if we don’t make teenagers read books about how it used to be. (STILL IS, btfw) Yes, people worry when a rule smacks of books being banned or censored. Got it. I got all that.

Still, of the change in curriculum, I say “Good.”

When a former student messaged to ask my thoughts, I wrote back:

You know, it doesn’t bother me. In fact, if black people (repped by the NAACP) are saying “Teaching these books is hurtful to us — they contribute to continuing racism,” then I’m okay with listening to the thoughts of those whose lived experiences are so different from mine. Also, the books aren’t being banned; they’ll still be in the libraries and available for students. And if students want to choose to read them for an essay they’ll write, they can. Basically, this is a change in curriculum. Public school teachers never get to chose what they teach; they are told by the district. So this change is not limiting the rights of teachers to choose. They always have to do what they’re told. Rather, this change seems to be about sending a message of “Maybe we’re finally ready to move away from an era where all the classics we require our kids to read are written by white people, centered on white people, and use the language that is a legacy of white people’s oppression.”

I’d rather, in the books my kids are required to read, that the institutions sending messages about what’s “good” and “important” ask them to read some books by black authors that are centered on the black experience and POV. Removing these two classics makes room for books that do just that.

Also, the objectionable word in these books is “nigger.” When I consider a different scenario, one in which my kids are required to read books that treat women as lesser citizens, casually calling them “cunts” because, hey, that’s what women have often been called historically, my reaction is: I’m not sure I want them to receive those messages through the school curriculum.

In the last couple days, as well, a friend put out a call on behalf of a reporter for the Minneapolis Star Tribune who was having trouble finding people who would chat with her and give quotes for a story she’s assigned to write on this Duluth debate. So I offered. After we spoke on the phone, I later sent her a follow-up message:

…my 17-year-old, Allegra, just got home from a ski meet, and I asked her thoughts about To Kill a Mockingbird. She says she’s glad she read it but that it’s not the only book that can teach young people about the history of racism in the U.S. For her, she has learned about racism from a variety of novels that she’s read, but, as she notes, not all kids are readers, so we can’t trust they will be part of racial discussions and learning unless there is some book required in high school English classes that addresses this difficult topic. Thus, she firmly believes there should be a novel required in the curriculum that asks classes to discuss race — but there’s no reason it needs to be To Kill a Mockingbird. As my husband and I talked with her about this, we noted there are many, many books that raise the issue and that we believe it would be more effective if students learn about racism through a book that is written by a person of color, with POC characters, so that the lens of the narrative is focused on the oppressed experience, not white perceptions of people of color.

Later last night, I got a message from a librarian friend in Pennsylvania, asking my thoughts. We had a good conversation about the difficulty of letting go of much-beloved books, especially when they are so ingrained in the culture. Yet I maintain my initial stance of “Good” about the change in curriculum.

It’s white people who are buzzing. It’s white people who are bemoaning the change. It’s white people who are worried that their kids won’t learn about the history of racism without these books being taught in the schools. It’s white people who need to learn to shut up and listen.

Because it’s black people, Native people, Latino people, Asian people — the millions with brown skin — who have been the target of racism, historically and currently. They have suffered lasting traumas under the systems white people created. Their children have had to sit in classrooms and ingest the words of white writers depicting white characters as saviors, especially when it comes to those poor black folk. And it’s people with brown skin who breathe the air of racism every hour of every day who are saying, “These books are hurtful to us. They are not helping to alleviate the problem.”

So why on Oprah’s round earth can’t white people shut the fuck up about their feelings and worries and hear what they are being told? The people oppressed say “Requiring these books is not good,” and the oppressors say, “But…”

I’m very glad there will be space in the public school English curriculum for different books to be taught. There are thousands of amazing novels written by authors with brown skin, telling amazing stories of people with brown skin — rich, evocative, empathy-building books that will help kids of color in the classroom feel seen and celebrated, that will jar white kids into understanding that although the focus has always been on them, there are other ways, other pains, other lives, and it’s essential they learn about our racist realities from the perspectives of those who have been held down the hardest and the longest. If white people are ever going to dismantle the systems they have built, they first have to be able to see them for what they are.

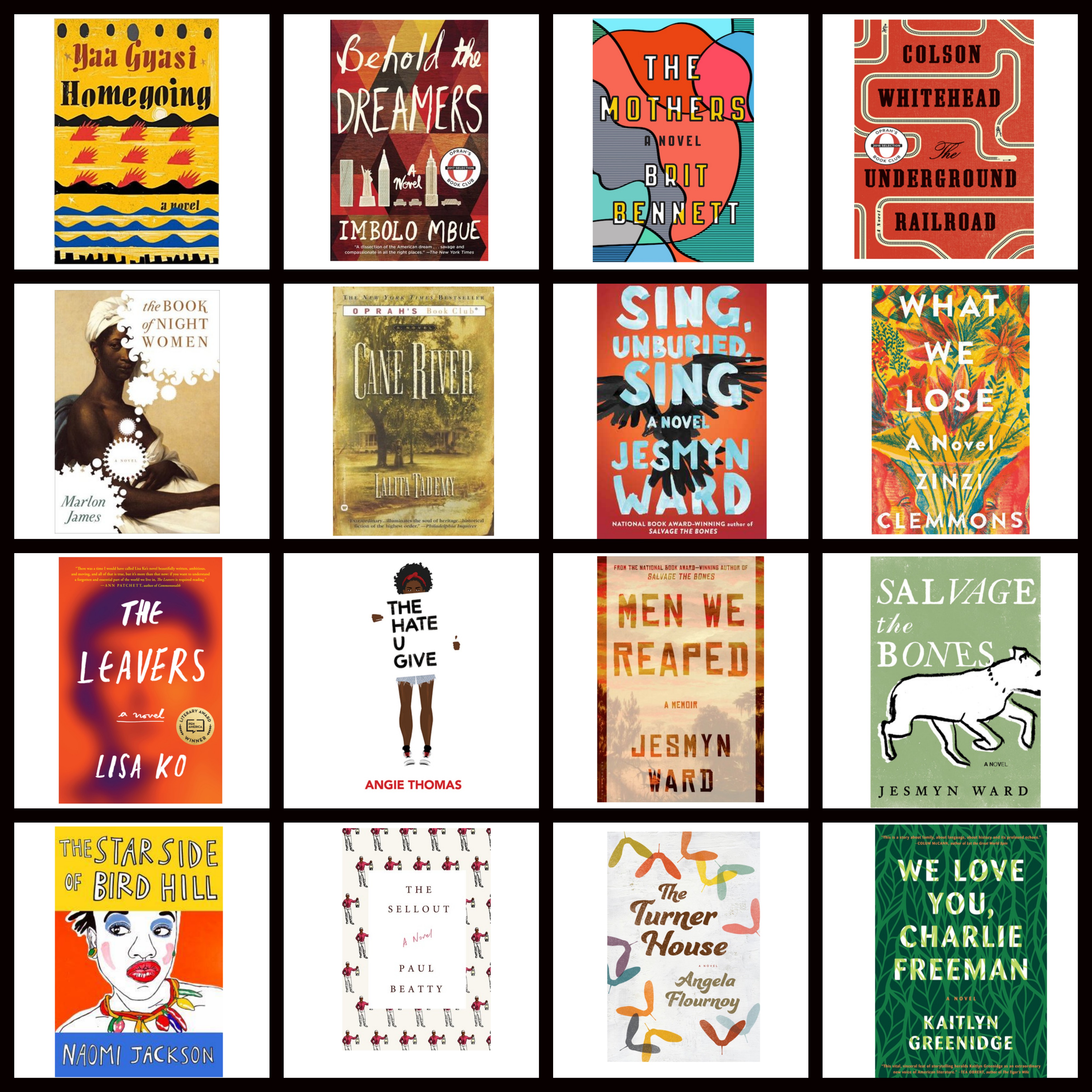

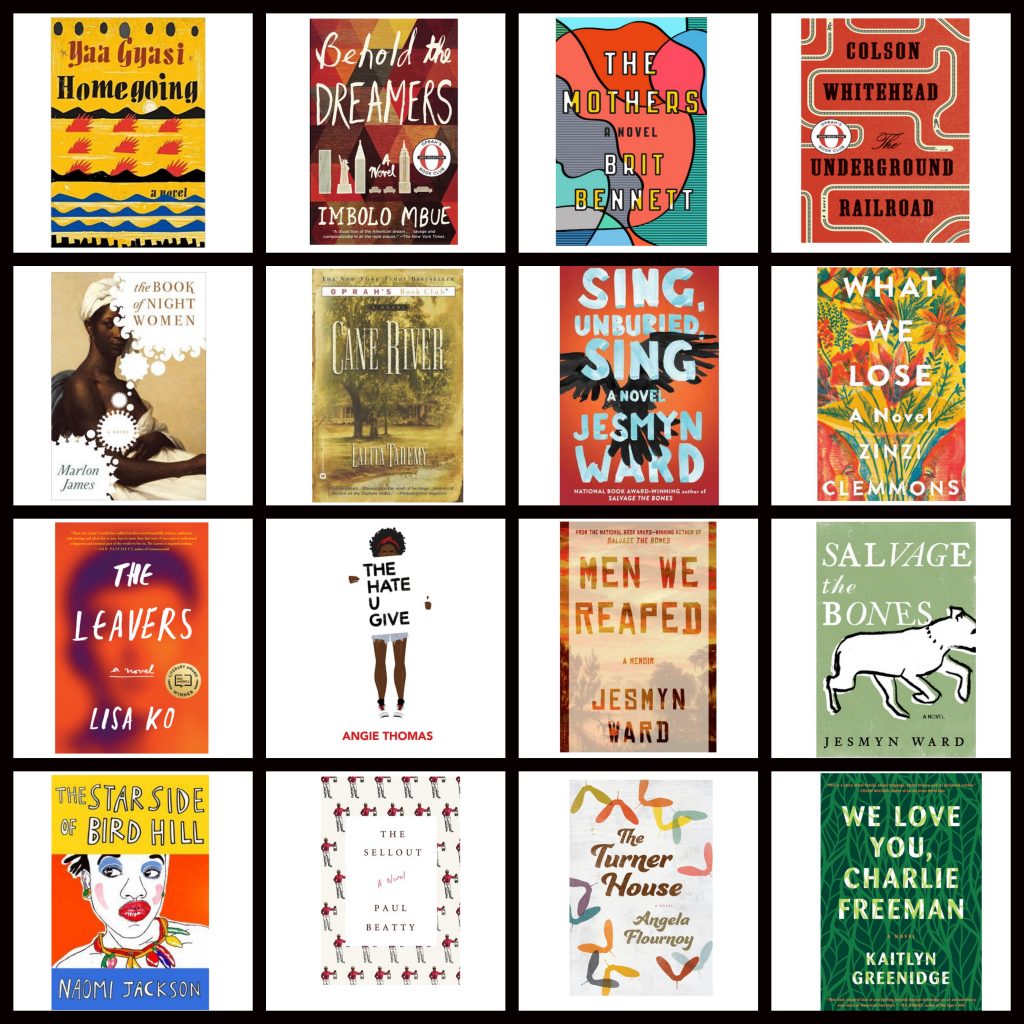

So good on you, Duluth Public Schools. And if you’re struggling to find new books to plug into the curriculum, and you’re not in the mood for classics by Sherman Alexie, Maya Angelou, R. K. Narayan, Jean Toomer, Margaret Walker, Lorraine Hansberry, Julia Alvarez, Jorge Luis Borges, Langston Hughes, Chinua Achebe, Osamu Dazai, Claude McKay, Paule Marshall, Zitkala-Sa, Toni Morrison, James Weldon Johnson, Junot Diaz, Sui Sin Far, Luther Standing Bear, Alice Walker, Nawal El Saadawi, Zora Neale Hurston, Sarah Winnemucca, Es’kia Mphahlele, Sandra Cisneros, Jhumpa Lahiri, James Baldwin, or Isabelle Allende, please feel free to consider a few of the books collaged below.

I’m an educator. I’m a parent. And I would LOVE for my students and my kids to read every last one of them.

Typing time: Can I get all blowhardy here and say “400 years”?

Editing time: Well, I mean, the spelling of Es’kia Mphahlele is something I had to look up.

Leave a Reply