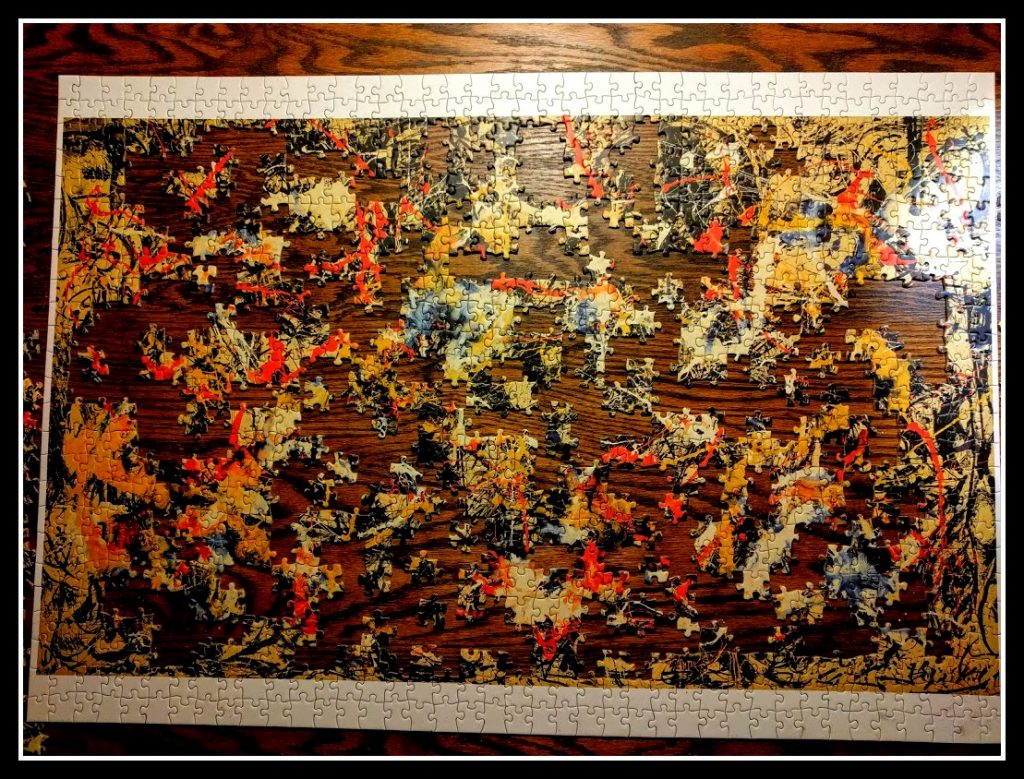

“This is fricking insane!” I yelled at the paint on the walls periodically as I spent half an hour trying to place a single piece into my new puzzle.

Jeezus, that paint wasn’t wearing well.

Cracks everywhere.

The slate color had always seemed appealing; mentally, I had complimented the previous owners for choosing a tone that managed to be simultaneously neutral and interesting.

But now.

SLATE? Who in the holy Chip and Joanna chooses slate-colored paint? Did they not realize every eventual crack, when future owners failed to update it, would jut in stark relief?

Diverting puzzle frustration into paint diatribe, I waved my hand wildly in the air, a protest against the evils of cracks. As I gestured, the puzzle piece went flying from my agitated fingers. A blip followed by a plink.

For the love of shitgibbons. Where did it go?

The thing had landed somewhere. Was it in one of the baskets by my feet? Was it under an unused Wii remote? Had it flown across the room? Was it resting in the slats of the rocking chair?

Dropping to my knees, I crawled around, lifting the edges of each of the six kilims in the room as the tv droned in the background about the new president’s cabinet picks, every last one of them anathematic to my values. Ahh, there it was. Picking up the wayward piece, I hoisted myself up, in the process clonking my head on the edge of the table.

A few days into it, one thing was already clear: this puzzle just might kill me.

Puzzling has long been an escape for me, a hobby offering retreat and replenishment, particularly during the winter months when the gardens are dormant.

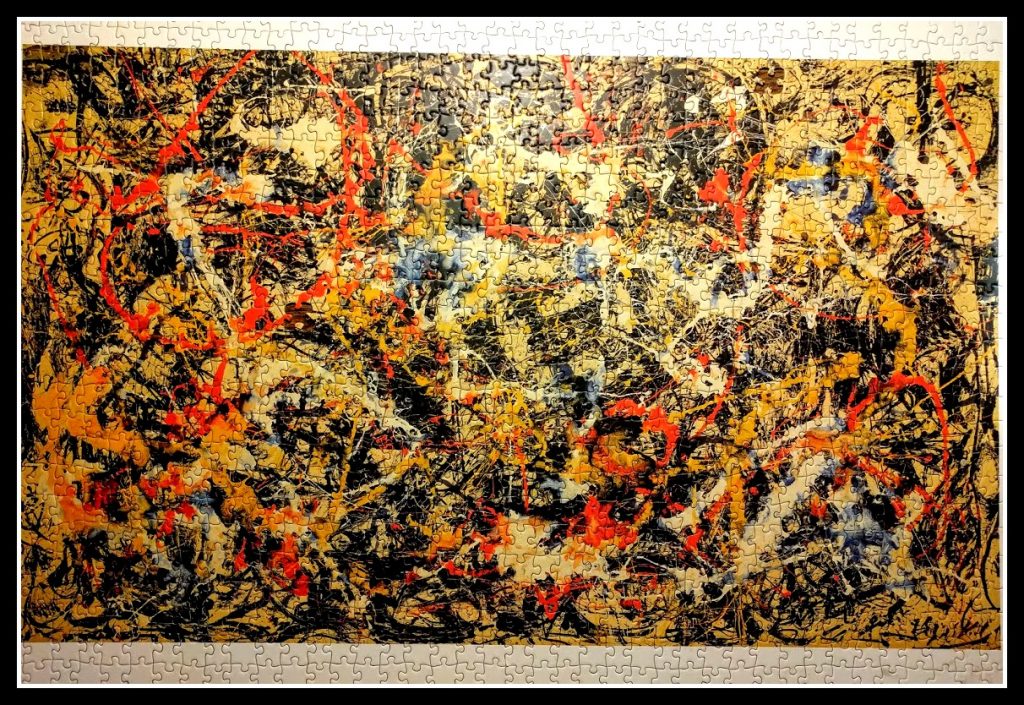

Until I tackled Convergence, 1952, the puzzle table was my safe place.

Until Convergence.

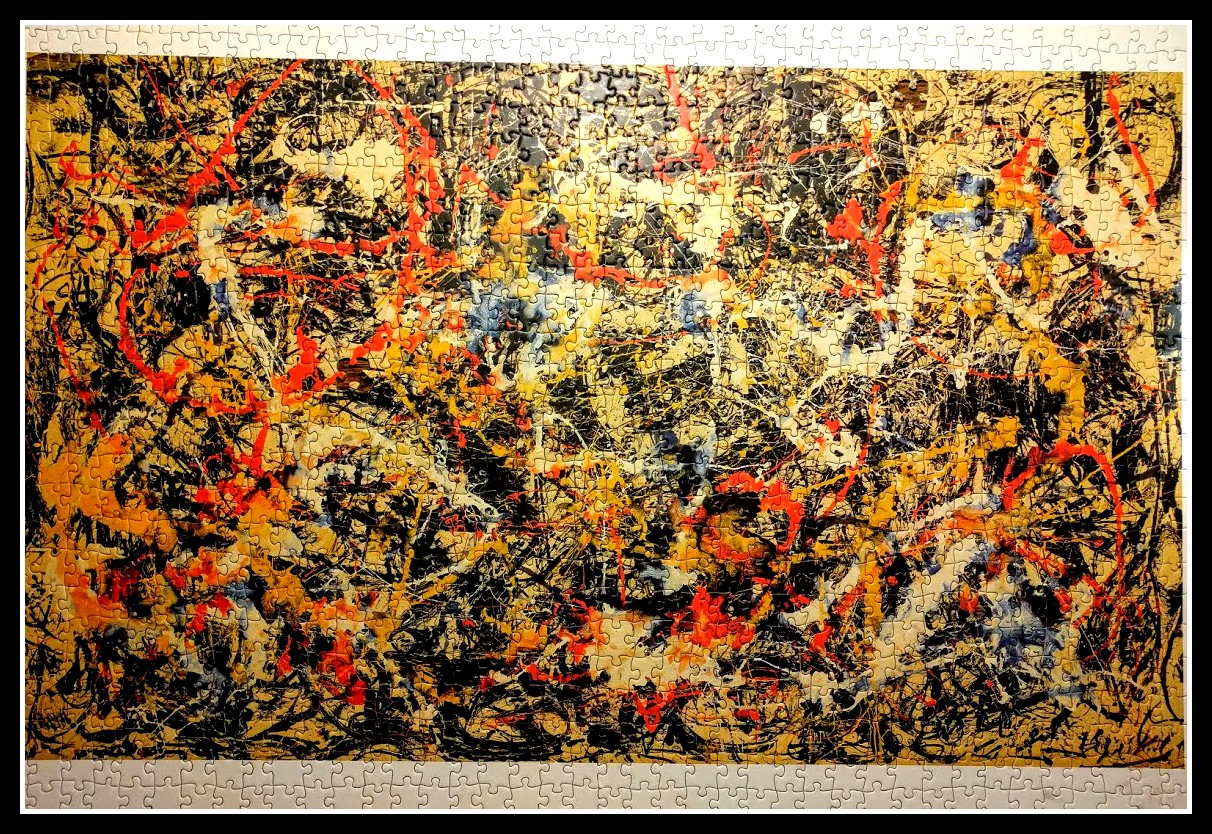

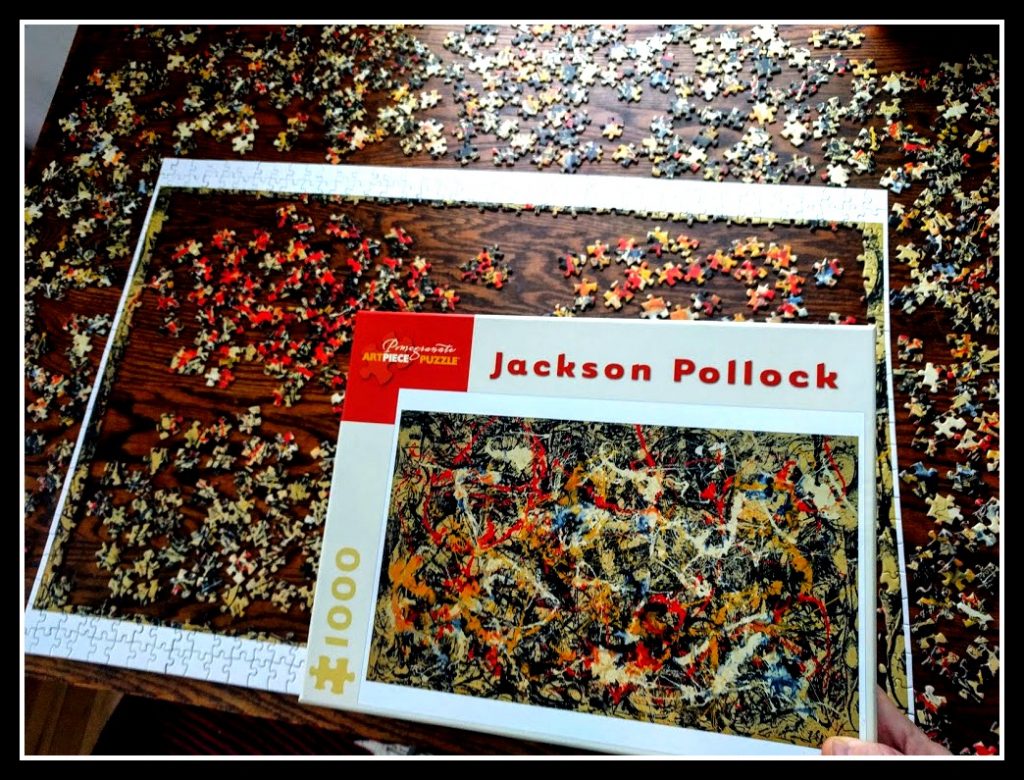

In 1964, the Springbok company released a 340-piece version of Pollock’s painting, promoting it as “the world’s most difficult puzzle.” On my table were 1,000 pieces.

Assembling the frame for the picture — a hundred or more indistinct white pieces, unrelenting in their sameness — was the easy part. Cardboard Nazis, they easily fell into lockstep with each other. But the colors? Oh, the colors! Complex, vivid, unpredictable, rich, they created a story I couldn’t control. Each time I sat down at the table, I would grab a bright piece and try to group it with its ostensible mates; each time I sat down at the table, I learned that like didn’t necessarily go with like in this modern classic, a painting channeling rebellion and protest.

One of the first things I did, upon starting it and being stymied by the layers of turmoil, was to google “Jackson Pollock mental health.” The person who created such vigorous, unchecked chaos must have struggled. I was sure of it. As it turns out, Pollock did suffer from clinical depression, but I had expected a strong history of mania, as well, to help explain the energy that churns throughout Convergence 1952.

Ah, but as is always the case, I knew nothing. Spinning exhaustedly inside a heavily partisan news cycle, I’d forgotten that not everyone who hurts my feelings necessarily runs high and hot.

And Pollock, like a madman tweeting in all caps, was hurting me.

I would sit at the table, then stand when my rear end fell asleep, then sit again. Up and down, bending and leaning, deliberately, carefully, with thought and organization, I tried to unlock Pollock’s vision. Selecting a single spot, I would glass slipper a succession of pieces into it. Initially, I’d look for pieces that made sense, given the context — say, light beige with streaks of black. After seventy of those failed, I’d stop looking at colors and pay attention only to shape. After another seventy fails, a heap of misses filling the open space more effectively than did supporters on the Mall at the Inauguration, I yowled at the stupid cracked slate walls while a preacher of prosperity gospel administered the oath of office to a self-aggrandizing Brand.

This damn puzzle was so different from anything in my previous experience, so far from making any kind of sense, so resistant to my attempts to crack its logic. It was defeating me. My safe place was hosting my nemesis.

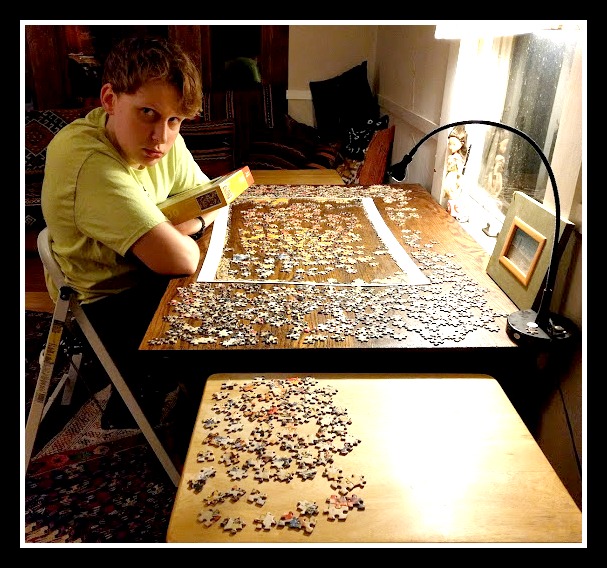

If I was going to beat this thing — and NO WAY was I giving over — I was going to need help. This beast threw me into a panic every time I thought about it; I needed to pull my people close, marshal our collective energies into tackling the challenge.

Attempting to be a good capitalist, I struck a deal: I would pay $3 per properly placed piece to the fourteen-year-old, he who had mentioned he was saving up to buy a new game. Although the new administration refuses to release the Brand’s tax returns because the election results proved “people didn’t care,” and although the new administration froze many federal agencies’ ability to report the results of their work publicly, I — in charge of my own self for the time being — made a loud and proud announcement to the cracked slate walls after Paco spent a focused half hour successfully finding homes for the ones with the wide wings and the ones with the narrow points:

“The pup got five pieces in. He wants a game that costs $15. I am buying the kid that game.”

Despite inhabiting this queer world of mind-bogging puzzles and politics, a place where a presidential counselor urges the public to “go buy Ivanka Trump stuff,” the eighth grader countered my paint-shouted pronouncement with exemplary graciousness: “No, Mom, I don’t want you to pay me. I just wanted to help you.”

One weekend, our friend Kirsten came to visit. Before her arrival, I set the terms of her visit.

“I’m going to need you to get 14 pieces into the puzzle before you can leave.”

Within minutes of surveying the chaos, her empathy was boundless. She felt the pain of all those random swirls and splattered drips; she ground her teeth with frustration at reds and blues that shared space uneasily. She understood the weeks of strangled pleas @AltJoce had been sending out to the world.

A warrior, she did her best to relieve my feelings of loneliness in a difficult land.

Nevertheless, on Sunday, when I turned my head for a quick second, she tossed her bags into her car and tore off, screeching down the alley.

She left the puzzle seven pieces the better.

SEVEN.

There was a tipping point where I. just. couldn’t. take. it. any. more.

One late night, while Seth Myers highlighted the ludicrous reality of a country governed by someone whose idea of nuance consists of jabbing stubby fingers into his opponents’ chests — “BAD!” yells the tired toddler when his teddy bear tips over — I realized I’d been pretending to attack the Pollock puzzle when in actuality I’d been sidling up to it fairly passively.

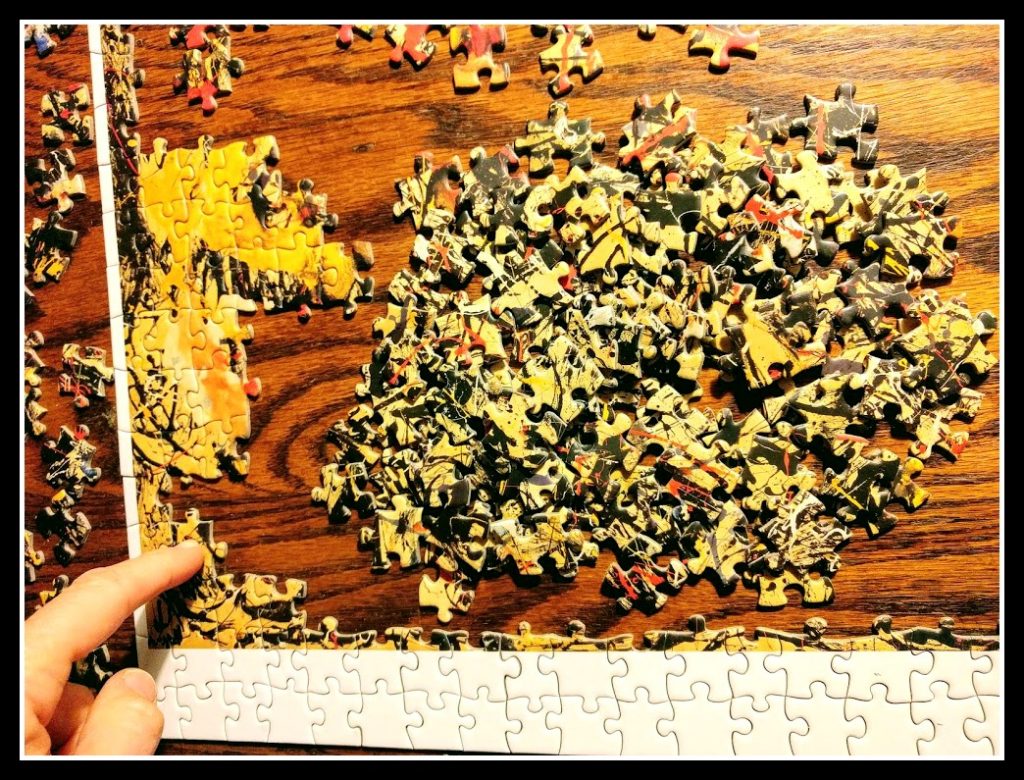

Until that moment, I’d approached Convergence the same way I approached all puzzles: I put together the border, I grouped related colors, I looked for clear connections, I alternated between attaching pieces to the existing lines and tacking together floating islands of neighbors. As though I was in charge, I’d been nation building. But. The nation was already built.

To be effective, I needed to change my tactics and observe — to snatch at every white snarl, every disappearing blood trail, every burst of sunshine. Instead of allowing myself to be ruled by despair, I needed to calm my innards down and ask, “What did he do?” and “How can I track what he did?”

To answer these questions, I had to do two things: 1) Clear out the noise; 2) Pay attention to the patterns.

It took me twenty minutes to move all the random pieces out of the frame and create clarity. It took me two more weeks — the lid of the box on my lap, a pair of cheaters on my face, a helpful husband in the kitchen — to decipher the master plan, comprising a thousand irregular pieces, and beat that fucker.

At no point did it make sense.

At no point did it get easier.

To the end, the vision was chaos. To the end, my brain whirled, often ineffectively, in the tornado of so many ideas layered so densely. For Pollock, the technique of laying down hard and vivid lines on top of a receding backdrop was purposeful. He conjured a tumult where attention can land anywhere, is demanded everywhere. Overwhelmed, the audience is left breathless.

It’s a cunning technique, the business of foreground dominating background, of drawing the eye to predetermined points while craziness hovers behind.

The audience needs to learn to pace itself. To look below the hard surface. To discern the overarching plan.

On the day a woman with more disdain for public schools than guns in their hallways was confirmed as the Secretary of Education, I finished the Pollock puzzle.

Fittingly, three pieces were missing.

Unable to scout them out on my own, I called in my most reliable reinforcement.

Converging on the kilims, Byron and I crawled around, pulling up the edges of the rugs bought in the Muslim country that had embraced our dazed family. We peeked into baskets.

Aha! He found one, placed it on the table, and stepped back, “You get the honor, of course.”

Still short by two, we moved Wii remotes, looked between the slats of the rocking chair, rubbed our heads against cracks in the paint.

We crouched. We stood. We lifted. We ducked. Eventually, we conceded.

Maybe part of the problem all along had been that we were trying to solve something that came out of the factory a few pieces short.

Leave a Reply