I first became aware of Caitlin Moran a couple years ago, when her book How to Be a Woman was creating a splash. In search of a read that was smart but didn’t make my tired brain hurt, I grabbed a copy. Almost immediately, I wished it was 1985 and that I was back in my freshman year of college, a time when multi-colored highlighters were always close at hand, prepped for assiduous application to the text. Each time I ran a thick, bright-yellow marker over a particularly meaningful paragraph of Balzac or Hegel, it meant I was engaged and, even more, able to spot the important things. Had I read How to Be a Woman in 1985, I could have slapped the book closed after reading the last page and then grabbed the volume with both hands and wrung a puddle of neon highlighter onto the industrial carpet in my dorm room. Every word would have been saturated with yellow ink.

For me to get all fangrrrly about Moran is no stretch. She’s funny, talky, full of gusto, a mother to two kids. Despite her easy appeal, though, I appreciated that How to Be a Woman challenged me to consider the immediacy and relevance of feminism in a world that I had dismissed as post-post-post-feminist. As well, my reading of this book intersected with arguments being made by a college friend of mine, Robin, in her blog posts such as the one titled Wherever I Go, Whatever I Do, I Have a Uterus. It also intersected with reports from watchdogs like VIDA (Women in Literary Arts) that juggernaut publications like The Atlantic, London Review of Books, New Republic, The Nation, and New York Review of Books devote a mind-blowing 75-80% of their annual coverage to men’s writing. My brain may be tired and actively avoiding circumstances of hurtingness, but when smart voices make points with forceful words and convincing statistics, the grey matter has nowhere to hide. After some mulling, in fact, the grey matter had to accept that feminism isn’t merely an historical movement from forty years ago. It’s a here-and-now issue, and my uterus and I needed to take it off the shelf.

Not incidentally, my uterus is wondrously dextrous. Last week, it put a stamp on an envelope. Woefully, the video camera’s batteries died during filming of this event.

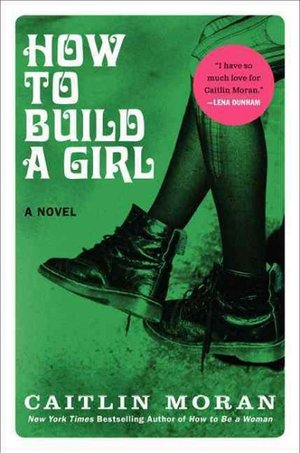

Because I enjoyed How to Be a Woman so very much, my hands got clappy when I saw that Moran had written a new novel, a coming-of-age story based loosely on her own experience growing up poor in the Midlands of England during the 1990s. As is true for Moran, the protagonist in How to Build a Girl is from a big, loving family, one that she nevertheless escapes during her teen years after lucking into a job in music journalism. Powered by her spirited voice, Moran’s writing here appeals to my criterion of No Brainy Hurty, yet it is appealingly full of brio–funny, thought-provoking, and incisive–and many passages made me want to elbow my sleeping husband and whisper loudly, “I just need to read these two pages out loud to you. No need to respond. Just lie there and look dopey. As you do.”

It was only the fact that Byron was a sleepwalker for several decades that kept my elbow tucked to my ribs. Actually, these days, the sleepwalking tendencies have been harnessed; it’s rare that he leaps out of bed to take a random wander around the property (sometimes a guy’s just gotta go stand in front of the open fridge for three minutes, in case someone put his car keys, or a rabbit, in there). Rather, when roused, he usually stays in the bed–while rearing up dramatically and pinning me to the thread count with an intense, brain-disconnected, baleful glare that would melt a lesser Feminist Wife.

All in all, even though I was nodding knowingly, shouting internal affirmations, and wanting to share some of Moran’s insightful passages with somebody, it seemed wise to let sleeping beaux lie. Instead, I simply reread the best passages three times and smugly noted that poor zzzz-ing Byron sure was missing out over there on his poofy pillow.

What I appreciated particularly about How to Build a Girl is that it weaves social commentary into the story line. It’s just this tendency that caused the New York Times‘ review of Moran’s latest to note, with some affection, that the book is occasionally “sloppy.” Long-time readers of this blog, and neighbors who have walked through my living room, know that I’m okay with “sloppy.” It’s sloppy, after all, that allows for asides about the postal abilities of a uterus and the potential presence of a rabbit in the refrigerator. Tight is over in Human Resources, taking messages on a tiny pad of paper. Sloppy is dancing on top of the copy machine, a half-drunk bottle of peach schnapps swinging wildly around her head, and she’s not coming down until someone cobbles together a ladder out of the goldenrod.

There are a few sloppy passages about class and poverty in How to Build a Girl that I want to copy, laminate, and hang up in my office. Then, when I have had it up. to. here with students not getting to class, or only sporting one shoe when they do get to the room, or not having the textbook by week eight, or munching pizza-flavored Goldfish for an hour while announcing it’s the only thing they’ve eaten all day,

I can retreat to my office and rediscover compassion in the laminated paragraphs sagging from the walls (damn cheap Scotch tape), in clunkily incorporated passages that remind “…the poor are seen as…animalistic. No classical music for us–no walking around National Trust properties or buying reclaimed flooring. We don’t have nostalgia. We don’t do yesterday. We can’t bear it. We don’t want to be reminded of our past, because it was awful: dying in mines, and slums, without literacy, or the vote. Without dignity. It was all so desperate then. That’s why the present and the future is for the poor–that’s the place in time for us: surviving now, hoping for the better later. We live now–for our instant hot, fast treats, to pep us up: sugar, a cigarette, a new fast song on the radio.

“You must never, never forget when you talk to someone poor, that it takes ten times the effort to get anywhere from a bad post code. It’s a miracle when someone from a bad post code gets anywhere…A miracle they do anything at all.”

Later in How to Build a Girl, after the main character of Johanna has banged around her teen years, collecting sexual experiences, applying ever-thicker eyeliner, tromping into clubs in her torn tights, she realizes her attempts to be cool and adult have, in fact, made her cruel. As Johanna reconsiders the kind of person she wants to be in the world, Moran works in a gorgeous tangent about cynicism and how it’s a way of coping with fear.

As someone who cultivated an attitude of irony through her teen years, eventually channeling it into a coat of cynicism, I had to adjust the reading lamp on the bed’s head board while reading these pages. I didn’t want to miss a word. Much of my adult life has been spent stripping away the shellac of cynicism, but I hadn’t necessarily realized that until Moran articulated it. Her Johanna, reflecting on why she had become so jaded, realizes it’s “Because I am still learning to walk and talk, and it is a million times easier to be cynical and wield a sword, than it is to be open-hearted and stand there, holding a balloon and a birthday cake, with the infinite potential to look foolish. Because I still don’t know what I really think or feel, and I’m throwing grenades and filling the air with smoke while I desperately, desperately try to get off the ground: to get elevation. Because I haven’t yet learned the simplest and most important thing of all: the world is difficult, and we are all breakable. So just be kind.”

Thank you, Caitlin Moran, for convincing me feminism still matters; for illuminating the ongoing problems with our classist cultures; for making me want to go out and buy a balloon and a birthday cake.

I’m counting down the years until I can hand your books to my daughter.

Leave a Reply